The changes to the Montana frontier ranching since the years Lewis and Clark traveled there have been less obvious perhaps, but no less remarkable.

Two Highline Ranching Families

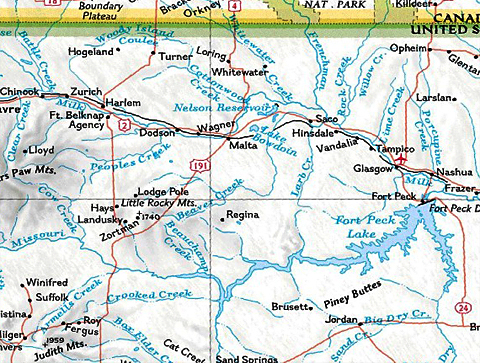

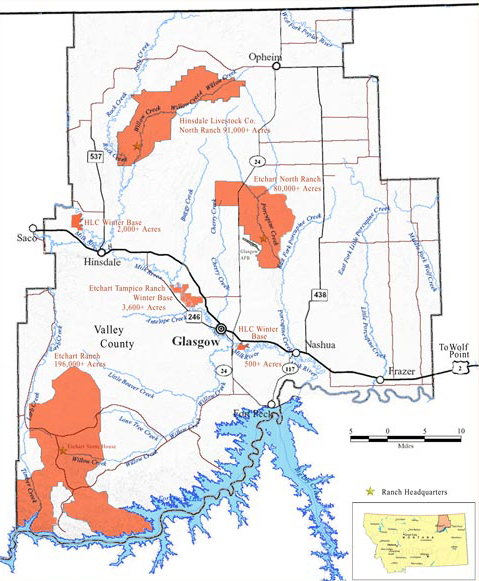

Part of the Highline in Northeastern Montana

To see labels, point to the image.

© 2003 National Geographic Oldings, Inc., TOPO!.

The black line between Chinook and Frazer represents the main line of the BNSF (Burlington Northern and Santa Fe) railroad, originally the Great Northern. It’s 166 miles between those two places via US Highway 2. Chinook (pop. 1,386 in 2000), the seat of Blaine County, was founded by the Great Northern Railroad in the late 1880s. It is 55 miles north of the Missouri River, and 28 miles south of the International boundary. Frazer (pop. 452) at first was a way-station on the Great Northern; it gained a post office in 1907, and is still a shipping-point for grain. It lies 65 miles south of the Canadian border. Glasgow (pop. 3,253), the oldest community in northeastern Montana, was created by the railroad in 1887.

Dated arrows indicate several of the campsites occupied by Lewis and Clark on their route west in 1805. For more views, see The Milk River.

After the fur trade waned in the late 1840s, the raising of cattle and sheep was among the first enterprises undertaken by Euro-Americans on the Upper Missouri. As Lewis and Clark had observed, the grazing potential of these sweeping grasslands was enormous. On 27 April 1805, a few miles west of the Yellowstone’s mouth, Captain Lewis admired “one of the handsomest plains I ever beheld”; on 29 April 1805, he exclaimed over an “extensive, fertile, and beautifull valley” of the river Clark named “Marthas” (now Big Muddy Creek); and on 20 May 1805, he rhapsodized over the Musselshell River bottom, with its “lands of excellent quality.” Both captains repeatedly noted the “whol face of the country . . . covered with herds of buffaloe, Elk & Antelopes.” But before this grazing potential could be realized, adequate transportation was needed to bring the region closer to markets and suppliers. Fort Benton was the head of navigation for the steamboats plying the Upper Missouri, but getting goods to and from the port was a challenging proposition, with few roads north of the river and those impassable much of the year.

Coming of the Railroad

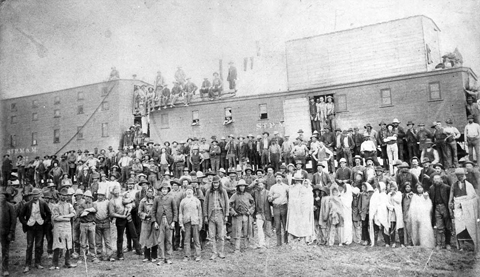

Originally captioned “When Our Gang Came Out from Supper,” this photograph documents St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway workers in Montana Territory in 1887. In eight months, between April and November of that year, these men laid 642 miles of track.

It was not until the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway Company (later the Great Northern Railway) traversed Montana’s upper tier in the late 1880s that ranching on a large scale became practicable there. The coming of this railroad, known as the Highline because it was the northernmost line in the region, also allowed for the founding of many of northeastern Montana’s towns. Many of them began as construction camps, section control stations, or market centers for the good of the railroad’s profit margin. The Great Northern, like other railroads in the West, had to build its own customer base by setting up an infrastructure and luring settlers into the region.

In other regions of Montana, stockgrowing had begun much earlier. For example, John Francis Grant first wintered cattle in the Deer Lodge Valley—a broad mountain valley midway between the Missouri and Bitterroot Rivers, transected by an Indian road Lewis and Clark knew of but had neither reason nor time to explore—in 1857. Phillip H. Poindexter and William C. Orr, who registered the first brand in Montana Territory, drove cattle from California into western Montana in the mid 1860s, establishing their vast ranch along the Beaverhead River, and Bozeman-area pioneer Nelson Story brought a herd of 3,000 longhorns into southwestern Montana in 1866. Pioneer stockman George McCone brought one of the first cattle herds into the Yellowstone River country in 1882; the Northern Pacific Railway reached the Yellowstone River in 1880 and was completed in 1883, allowing McCone and other Montana stockmen quick and economical access to eastern markets.

Conrad Kohrs, who had purchased Johnny Grant’s ranch at Deer Lodge and then expanded into the Sun River country, was among the first stockmen to take advantage of the northern rail line. When, in 1884, “the Sun River range was getting crowded with sheep,” Kohrs moved two large cattle herds into the Judith Basin (Meriwether Lewis saw the Judith Mountains in the distance on 24 May 1805), onto what Kohrs called the Fort Maginnis Range. “[W]e had,” he wrote, “many miles of country.” Northeast of Lewistown, Fort Maginnis (1880) was the last military outpost built in Montana, following the Custer incident of 1876 that aroused fears on the High Plains. Then, in 1887, once the Great Northern reached as far as Havre, Kohrs only had to trail his cattle a relatively short distance to catch the train at Bowdoin or Chinook (before 1887, his cowboys had to trail the Fort Maginnis cattle all the way to the Northern Pacific line, at Custer on the Yellowstone River).[1]Conrad Kohrs, Conrad Kohrs: An Autobiography (Polson, MT: privately printed, 1977), 80, 99.

The Newby Family

It has all been worthwhile,

and I would go through it again,

but we earned everything we have.

An early rancher on the Highline, Emory C. Newby (no traceable relation to the author), did not arrive in the Chinook area until the late 1880s, at the same time as the Great Northern. (The Great Northern’s transcontinental line was completed in 1893.) Of Quaker stock and the son of a farmer, Newby came from Henry County, Indiana. He and his wife Margaret settled in April 1889 on 160 acres near the new town of Chinook—”which then contained only two houses”; the Chinook post office was established that same year. As Progressive Men of the State of Montana reported, “He forthwith brought to bear his best energies, and devoted careful attention to the improvement of his place for the conducting of general farming and the raising of cattle.” Surely the Great Northern, and its access to midwestern markets, helped make this prosperity possible.[2]“Emory Cecil Newby,” Progressive Men of the State of Montana, Illustrated (Chicago: A. W. Bowen & Company, ca. 1901), 1744.

In a reminiscence, Emory and Margaret Newby’s son, Arthur Davenport Newby, recalled those early years:

[Our father] met us when we arrived and took us out to the ranch. All along the trail (there was no road) we dodged piles of buffalo bones and he told us that the buffalo had been killed off by white hunters for their hides a year or two earlier. Our ranch was literally covered by piles of bones. They lay just as they had fallen when killed and most places one could step from one pile of bones to the next one without ever touching the ground. Prior to the killing of the buffalo thou- sands of them had roamed the Milk River Valley. . . . The year following our arrival the Indians gathered the bones and sold them to Easterners who took them to grind into fertilizer.

The day after our arrival my mother wanted to see what sort of fish Milk River contained and as our shack was only eighty rods from the River, she got a hook and line and we walked over to the river—but, oh, such a river. It was early May and the river was nearly full of thick, yellow muddy water. Mother said, “I see why they call it Milk River.” It was as thick as cream and it was two months before we were able to catch any fish.

It was a wonderful country for a boy to grow up in. I loved to ride and there were no fences nor schools then so I had lots of time for riding and a wide free country to ride in.[3]Arthur Davenport Newby, “Early Days in Montana,” Montana Farmer-Stockman, 15 May 1955.

Arthur Newby remembered his first encounters with Indian traditions:

While riding south of the river I saw what looked like a large basket upside down on top of a little hill. It was woven of red willows . . . like a round-bottomed basket, but it had a little opening on the east side facing the rising sun. I got down on my hands and knees and peered in. There sitting facing the opening was a mummified face of an Indian staring back at me. All his possessions were about his feet. It was an Assiniboine Indian’s grave. I can still shut my eyes and see that old and wrinkled face. It made me feel very queer inside. I was only about twelve years old at that time.[4]Ibid.

Another Newby son, Terrell C., recounted in verse and prose his first years on the Highline. He wrote of the ever-present wind, claiming that as a small boy “I used to take a shingle under each arm and fly most of the way to school, two and one half miles.” He too remembered the last vestiges of the great bison herds: “I have seen bones, stacked along the siding of the Great Northern R.R., higher than the cattle cars, in which they were to be shipped.” And he recalled ration days at Fort Belknap just across the river from the Newby ranch—and how the Newby children benefited from the disdain the Indians felt for Euro-American clothes:

The Government . . . gave all kinds of clothing to the Indians every month. Of course they would not wear the shoes, stockings, suspenders etc. and so they peddled them among the settlers. This is about the only way we small children would get clothes. I remember the coldest winter I ever experienced. I had no shoes to wear. All the rest of my brothers got a pair but the Indians did not have a pair to fit me so I had to do without.[5]Terrell C. Newby, unpublished poems and prose, courtesy of Terrell Newby, Seattle, WA.

In an interview, family matriarch Margaret Newby—at the age of 95 in 1954—underscored the challenges the family faced in their first years on the ranch. Because of drought, they did not have a crop for six years, and once “they had a beautiful crop of oats that Emory Newby was very proud of and the hail came and ruined it.” At first, they subsisted on canned goods and “all the fish they wanted to eat, white fish, pike and cat fish a yard long.” The interviewer added, “Mrs. Newby spoke of the advertisements that made them think that Montana was a very wonderful place. ‘But,’ she said, ‘they did not tell everything. Not a word about the millions of mosquitoes. And I could not go to a store and buy mosquito bar netting to put over the windows.'” The reporter continued, “They hauled their water from the river, made their own clothes, even their underwear. . . . Mrs. Newby said, ‘It has all been worthwhile and I would go through it again, but we earned everything we have.'” Clearly this life was not for everyone.[6]“Incidents in the Lives of the Emory and Margaret Newby Family in the Early Days of Chinook in Montana Territory (as told to a reporter),” publication name, location, and date unknown, … Continue reading

The Etchart Family

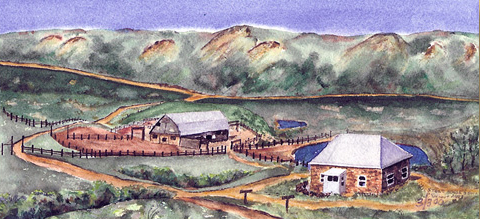

“The finest grass country” John Etchart had ever seen, looking east from the Stone House Ranch, south of Glasgow, Montana.

To prosper on the Highline required (and requires) qualities of independence and determination, plus plenty of skill, hard work, and luck. Rancher Gene Etchart, recently retired at age 90, speaks of his lifetime’s work running one of the largest cattle operations in northeastern Montana as “just like managing any other business.”[7]Gene Etchart, interview with the author, Glasgow, MT, 22-23 October 2006 (hereafter G. Etchart, Newby interview). An excellent interview with Gene Etchart by Brian Kahn, Home Ground Radio, was … Continue reading Barbara Cosens, who worked with Etchart in her role as a staff attorney for the Montana Reserved Water Rights Compact Commission (on which Etchart has served for several years), believes that Etchart’s success has a great deal to do with his openness to new technologies, his willingness to embrace the new.[8]Barbara Cosens, conversation with the author, Helena, MT, summer 2006.

His business acumen—and this predilection for innovation—come naturally to Etchart. Of French Basque heritage, he is the son of John (originally Jean) and Catherine Etchart, who came to the Upper Missouri in 1911 or thereabouts in search of new opportunities. (Lying within both Spain and France, the traditional Basque territory sits on the slopes of the Western Pyrenees Mountains, on the Bay of Biscay. Basque traditions of inheritance sought to preserve family landholdings intact, and generally property was transferred to a single male heir, usually the eldest. This meant that enterprising young members of Basque families—like John Etchart—traveled elsewhere to find their livelihoods.)

Before arriving in Montana, John Etchart had already spent a decade in the United States, first coming to California in 1900 and then—California having become too crowded to suit him—settling in Nevada, where he engaged in the sheep business. “Settling” is not quite the right term: On the wide-open range of Nevada at that time, John Etchart, together with a brother and a cousin, ran upwards of 20,000 head of sheep on a purely “nomadic” basis, moving camp each morning in search of the best grass and water. By 1910, Nevada was no longer so wide open; in 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt had created the U.S. Forest Service and soon the Forest Service set limits on the number of sheep that could graze on the federal forests (often the best rangelands in Nevada). At that point, the three young Basque sheepmen sold their herd and returned to France.

There John re-encountered Catherine Urquilux, who he remembered as a little neighbor girl, and found that she had “blossomed into a beautiful finished young lady.” John asked for her hand in marriage, was gladly accepted, and then returned to the States. While in the Pyrenees, he had encountered a fellow Basque who had recently sold a ranch in northeastern Montana. Before returning to Nevada, the rancher told John, “just take a look” at Montana. Gene Etchart recalls:

My Dad told me that when he first looked at the badlands country south of Saco . . . he was not all that favorably impressed until he came to the south hills surrounding the present Stone House Ranch. . . . he fell in love with it and purchased the ranch from the owner. . . . My Dad told me more than once that the country around the Stone House was the finest grass country he had seen . . . and that took in quite a bit of territory ranging from the Pyrenees Mountains through California, Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, and western Montana.

The Stone House Ranch, situated south of Glasgow close to the Missouri, was so-named because, in hopes of helping his new bride feel at home in the new country, John Etchart hired a pair of neighboring homesteaders, who were also stonemasons, to construct—out of local materials—a house and barn in the Pyrenees style. John had made a deal with Catherine. If, after two years, she did not want to remain in northeastern Montana, he would return to France with her. But both of the Etcharts fell in love with the country and the ranching life—and neither returned to the old country, even for a visit.

From the beginning, John Etchart was entrepreneurial, working hard to grow his business. In Montana, he started out raising sheep, and blessed with capital from the sale of his Nevada herd, he began to acquire neighboring ranches and homesteads.

He particularly sought to acquire lands that had springs or other permanent sources of water. In those early years, competition for the public domain was fierce; anyone could use it, without restriction. Herds of semi-wild horses and sheep bands owned by fly-by-night outfits vied for forage with the herds of, in Gene Etchart’s words, “more legitimate tax-paying, landowning” ranchers. This led to overgrazing, and the situation, made worse by severe drought, continued for many years. As Etchart writes, it “invited the coming of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934 to bring public lands under management to benefit an overgrazed resource. The Taylor Grazing Act marked the end of “the wide-open era.”

Access to water was one key to success, and so was the ability to provide winter feed for one’s herds (the itinerant sheep outfits, lacking wintering grounds of their own, were at the mercy of the often brutal weather). John Etchart acquired rich bottom lands along the Missouri, where he could raise his own hay, and also purchased hay from other Missouri River ranchers. The Stone House Ranch throve, and by 1920 it had expanded as much as it logically could south of the Milk River.

John began acquiring new lands to the north of Nashua, on Big Porcupine Creek. While these were excellent summer grazing lands, they lacked good winter range, and so John purchased a well-established farm near Tampico—one of “the first large irrigated places in the whole Milk River Valley . . . promoted as a model experimental farm” by Great Northern Railway magnate James J. Hill. There the Etcharts could produce plenty of winter feed. To expedite shipment of his wool, John built a set of corrals and a shearing plant southeast of the railroad stop of Hinsdale. In a peak year, they would shear as many as 30,000 sheep, including those of neighboring ranchers. The ranch continued to grow as opportunities arose, and the Etcharts gradually phased out sheep and turned to cattle, because the larger animals were less susceptible to predators and because skilled sheepherders became increasingly difficult to find.[9]Ibid., 42, 41.

Changes Since Lewis and Clark

Etchart Ranches in Valley County, Montana (2007)

To see labels, point to the image.

Etchart Family Album.

This map shows the ranches operated by the Etchart family as of about 1980. The two units north of U.S. 2 (the Highline highway) have since been sold. The Tampico and other southern units are now owned and operated by Page-Whitham Land & Livestock Company. All of the ranches consist of deeded private lands intermingled with lands leased from the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Fort Peck Indian Reservation, federally reserved school lands, and Valley County.

More than sixty percent of forage for wildlife and livestock is grown on deeded private lands. Fifty percent of the total range forage production is available for livestock, while one hundred percent of the production from those lands is available for wildlife forage and habitat the year around. As a community courtesy the Etchart family has always allowed free and open access to their ranchlands for all sportsmen, other multiple-users, and their guests.

Valley County, Montana, contains 5,062 square miles. In 1980 the combined Etchart ranches consisted of more than 370,000 acres, or more than 578 square miles.

When asked what he considers the most significant changes on the Upper Missouri in the two centuries since Lewis and Clark, Gene Etchart responds without hesitation. In Lewis and Clark’s time and even when Gene’s father took over the Stone House Ranch in the first decade of the 20th century, the region was a wilderness. “It is still largely unchanged,” he adds, but there are several major differences: first, the bison grazing this landscape have been replaced by cattle; second, the formerly open “country is fenced up into pastures”; third, there are hundreds of small reservoirs built by stockmen (often in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management and other agencies), making possible better distribution of grazing for the ultimate benefit of the range; and fourth, the public domain is controlled by laws, like the Taylor Grazing Act and the Montana Grass Conservation Act, aimed at keeping it productive.[10]G. Etchart, Newby interview.

As the open range was fenced into pastures, ranchers realized that they needed to develop localized water sources within each parcel they managed. As an example, Gene points to an 85,000-acre ranch his family recently sold, where there are something in the vicinity of 75 small reservoirs; those on leased public lands the Etcharts developed in concert with federal and state agencies (the Etcharts maintained all 75, whether they were on public or private lands). At the time of Lewis and Clark, Gene notes, there would have been very few places in northeastern Montana with permanent water, and so animals, including the vast herds of bison, must have congregated in the river bottoms. These small manmade reservoirs capture rainfall and spring runoff and assure, in Gene’s words, “better distribution of grazing by both livestock and wildlife.[11]Ibid.

Historian Gerald D. Nash notes, “Before the Great Depression, all public land had been open to anyone wishing to use them for stock grazing free of charge.” Under this policy, as Gene recalls, the public domain on the Highline (and elsewhere) was carrying too many animals and grew severely overgrazed. The Taylor Grazing Act, passed by Congress in 1934, was intended to “halt this injury to the public grazing lands” and to “stabilize the livestock industry dependent on the public range.”[12]Gerald D. Nash, The Federal Landscape: An Economic History of the Twentieth-Century West (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999), 32.

With the passage of the Act, any rancher wanting to graze animals on the public domain had to secure a permit, pay a fee, and agree to follow certain guidelines. To receive a permit, a rancher had to have a permanent home base of operations and a sufficient source of feed to sustain a herd over the winter. These rules meant that itinerant sheep and cattle outfits, like those formerly found in northeastern Montana, could no longer use public grazing lands as their sole source of feed. Advisory boards governed each grazing district under the Act, allowing for a measure of local control.

At this juncture, Gene Etchart feels that the Taylor Grazing Act and related state laws have had a “tremendously favorable impact on Montana ranching, especially in the areas of large public lands concentration.” He quotes pioneer New Mexico sheepman Floyd Lee as saying that the Taylor Grazing Act was the “most significant change in public land policy, in the history of man, that did not result in the firing of a shot or the spilling of a single drop of blood.” Not only did the Act stabilize the ranching economy, Gene notes, but it has also “produced broad benefits for society as a whole . . . [including] increased property tax revenues, more revenue for local economies such as ranch suppliers, vastly improved wildlife numbers and availability,” with the Milk River country gaining a reputation for excellent hunting, especially of whitetail deer and ringneck pheasants. Despite these benefits, Gene recalls, “Everyone using the big badland commons between the Milk and Missouri rivers . . . [was] affected in various degrees and some adversely by the base property and feed production requirements” of the Taylor Act. In fact, “many did not survive,” in part because of another federal initiative, the construction of the great Fort Peck Dam on the Missouri and the consequent condemnation and loss by flooding of riverbottom lands that provided winter feed for many operations. Even the Etchart operation, with its large landholdings, found itself threatened by the conjunction of the two federal efforts.[13]Gene Etchart, “Some of the Impacts of Federal Legislation and Programs in the Milk River Country of North Central Montana,” unpublished manuscript.

Hard Winters

The Last of the 5,000 or Waiting for a Chinook

by Charles M. Russell (1864–1926)

Used with permission from the Montana Stockgrowers Association, Helena, Montana.

Charley Russell’s watercolor, called The Last of the 5,000 or Waiting for a Chinook depicts one of Kaufman’s last steers standing—humped up and emaciated—in a snowdrift, while hungry wolves lurk patiently nearby. Chinook is an Indian word denoting a warm, dry wind that unexpectedly descends the leeward side of a mountain range in wintertime, melting snow on the plain and making grass temporarily available to cattle and wild game.

Not just new federal projects and changes in federal law proved challenging. Drought, brutal winters, plagues of grasshoppers, and the world economic depression of the 1930s threatened the Etcharts’ success. Particularly devastating was the winter of 1936, which killed one-third of the Etcharts’ herd—already diminished because of prolonged drought and market forces. John would later joke that the “sheepmen here in northeast Montana had developed a sheep that could summer without grass or water and that if it were genetically possible to cross sheep with bears so that they could hibernate through the winter maybe a profit with sheep might be possible again!”[14]Gene Etchart, The Way It Was, 45.

Montana ranchers measured tough winters by the standard of the devastating winter of 1886-1887, which resulted in losses of between 50 and 90 percent of the territory’s livestock herds. After a terribly dry summer and with cattle prices low, the Northern Plains went into the winter with too many cattle on a range out of which “every vestige of vigor and growth had been beaten.”[15]Quoted in Robert S. Fletcher, “That Hard Winter in Montana, 1186-1887,” Agricultural History, Vol. 4, No. 4 (October 1930), 124; original source for quote was Weekly Yellowstone Journal … Continue reading Fires on the range destroyed any grass remaining, and most ranchers had not put up winter feed for their animals. They expected the open range to provide adequate forage. The first storms hit in November, and storm after storm, with sub-zero temperatures, blanketed the plains until March. In his classic article on the winter’s losses, Robert S. Fletcher wrote:

The cattle wandered around and attempted to rustle at first, but as the snow grew deeper and the crust harder and the cold continued intense, many of them gave up and huddled together under cut-banks or in the lee of cottonwood groves. Some drifted into the streets of the towns, standing about the livery stable manure piles where they could pick up a few wisps of straw.[16]Fletcher, “That Hard Winter,” 125; Fletcher’s source was again the Weekly Yellowstone Journal, various issues in January, February, March,and April 1887.

That winter, famed western painter Charles M. Russell was working for the OH Ranch in the Judith Basin, south of Fort Benton. Ranch owner Louis Kaufman of Helena had written the ranch foreman, Jesse Phelps, asking for a report of the condition of his herd. Russell later recalled:

Jesse says to me, “I must write a letter to Louie and tell him how tough it is.” I was sitting at the table with him and I said, “I’ll make a sketch to go with it.” So I made one, a small water color about the size of a postal card, and I said to Jesse, “Put that in your letter.” He looked at it and said, “Hell, he don’t need a letter, this will be enough.”[17]Quoted on “The Cowboy Poetry of Charlie Russell’s Stagecoach” website, www.charlierussell.org/lastofthe5000.htm

The big die-off of ’86-’87 brought change to Montana’s cattle industry. First and foremost, the winter revealed the vulnerability of an industry—in a drought-prone region—dependent on range forage for the survival of its stock. Robert Fletcher noted, “Most northern cattlemen were persuaded that it was unwise to run cows and calves on the range without any provision for feed or shelter in case of a blizzard.” This meant smaller herds “for which feed and shelter for at least part of the winter were furnished.”[18]Fletcher, “That Hard Winter,” 130.

Even with the most careful preparations, hard winters continued to threaten the livelihoods of Montana ranchers. John Etchart told son Gene about the winter of 1915-1916, during which the Etcharts lost about half of their herd of 16,000 sheep. In his own experience, Gene recalls the 1936 winter in vivid detail, and it is worth quoting his account at some length to understand the truly epic challenges that winter presented to the Etchart operation (and all of their neighbors on the Highline):

[W]e were caught by a bad snow storm with very deep snow early, probably late November or early December. Two bands of sheep were worked into Timber Creek which was the closest place where they might find food and shelter, while the rest were trailed single file through snow belly deep to a saddle horse towards hay on the Missouri River. . . . The weather stayed very cold and the snow kept piling up. The sheep could not forage along the trail and the going was exceedingly slow, causing them to lose weight and condition very rapidly. . . .

[They] finally made it to the river where they could be fed hay. The snow was very deep, probably in excess of three feet and it was difficult to get hay to the sheep. . . . [M]any of them perished right on the feeding grounds due to extreme cold. . . . the temperature went to 70 below every night for a week and 30 below represented the high temperatures. . . . I recall seeing magpies, which have to be the toughest varmints alive, inside a hay-roofed shed, that were so cold that they could neither walk nor fly. . . . I have never witnessed this phenomenon before or since.[19]Gene Etchart, “Hard Winters,” The John and Catherine Etchart Famly Album (Glasgow, MT: privately printed, 2007), 32-33.

The first chinook winds that year came in mid-March, melting the deep snow, and the Etcharts began driving their surviving sheep from the Missouri to range near the Stone House ranchstead. Murphy’s Law, in Gene’s words, prevailed, and a “very bad” spring snowstorm caught the sheep in early April. Ironically, the sheeps’ shelters served to capture enormous drifts, sufficient to “bury many of these weakened sheep alive”:

Our crews worked frantically with scoop shovels to free these sheep. . . . To find them was like looking for a needle in a haystack because at first only those covered by a small amount of snow could be found. As days passed the rising heat from the sheeps’ bodies and breathing created little hollow chimneys and gave a clue on the surface as to where to dig to rescue sheep, some as much as six to eight feet below the top of the drifts.

Of the sheep uncovered by the crews, few survived that had been buried for more than a week. In one band of yearling ewes alone, more than 300 died, “most . . . by suffocation.”[20]Ibid, 33.

Another brutal winter hit in 1949, but things had changed. Instead of feeding with horse-drawn bobsleds and using horses to move men through the deep snow, the Etcharts now used “bulldozers, semi-trucks, airplanes, etc.” to break trail, deliver feed where needed, and move from camp to camp. Even so, the ’49-’50 winter challenged this new technology. Again, snow fell early and did not melt, and as January hit, the cold only deepened (“fifty below zero was not uncommon”), as did the snow (to nearly three feet). The cattle were stranded wherever they stood when the first storms hit, and feed stocks grew low.[21]Ibid.

The Etchart crew prepared for the worst. They “built maybe one of the first ever cabs for a D7 Cat” (in the Etchart tradition of customizing machinery as needed), and with three trucks loaded with “fuel, groceries, cotton seed cake” and the Cat breaking trail, they headed to the south ranch to provide relief. After two days and a night of slow going, they finally hit a drift the dozer couldn’t broach:

We were all cold and tired and loaded up the supplies that would freeze, along with five people into the cab of that D7 (which was not an easy job) and started our trip to the Carnahan camp. . . . The Cat without trying to doze the snow made a good snowmobile machine and walked right over the drifts.[22]Ibid, 34.

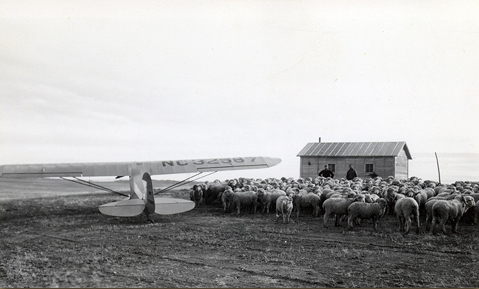

An important early aviator on the Highline, Gene kept “tabs on the situation using a little Aronica Champ airplane on skis:”

It hauled all the groceries, shuffled cowboys and sheepherders and was generally indispensable. The snow was so deep and hard that five miles was about the farthest distance you could travel with a grain fed saddle horse.

We got the roads open without County help. For several trips we used two D7 Cats which would start simultaneously, one from the south country and another from the Ft. Peck highway until they met. . . . When the Cats met in the middle we would usually have a bunch of trucks tailgating the southbound dozer and ready to go into Timber Creek where most of the cattle . . . were being fed near the artesian water.[23]Ibid.

Gene notes that forty-five miles separated the starting points for the two dozers. “Always on these road-opening, snowplowing trips,” the caravan of trucks included as many as thirteen vehicles loaded with hay, “a mixture of smaller trucks and semis.” The smaller trucks were needed for the descent to Timber Creek; the road was simply too steep and rough for the semis.

That winter, despite its severity, the Etcharts lost almost no sheep while their cattle losses stayed in the 10 to 15 percent range, much lower than in ’36-’37. The new technologies clearly had their uses.

Mechanization

The use of more sophisticated and powerful technologies continued to change the ways in which Highline ranchers did their work. As early as 1930, E. G. Nourse, writing in The American Economic Review, noted “Some Economic and Social Accompaniments of the Mechanization of Agriculture.” Nourse saw mechanization as primarily a social as well as an economic good, because it allowed farmers and ranchers to grow ever more efficient and productive. He minimized the “shrinking of our rural population” as a negative impact of mechanization. He might have been talking about the Highline when he noted that “many lands classed as inferior in the horse age because of their remoteness from the railway shipping point, from the improved highway, or from the farmstead have had their accessibility, and hence their economic productivity, very much increased by the introduction of the tractor, the truck, and the automobile.”[24]E. G. Nourse, “Some Economic and Social Accompaniments of the Mechanization of Agriculture,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 20, No. 1, Supplement, Papers and Proceedings of the … Continue reading

A beaverslide hay stacker at work on the Etchart ranch at Tampico. John Etchart is driving the team that pulls a load of hay up the slide until it is dumped atop the stack. This stacker was built in the shop at Tampico from “plans borrowed from Big Hole ranchers.”

The Etchart operation offers a prime example of the effective use of new technologies—not just during hard winters—in making this challenging landscape more productive,and rendering large-scale ranching viable. It also offers prime examples of how populations, human and animal, have shrunk as the dynamics of agriculture change.

Gene Etchart remembers back to the mid 1920s, when the range was still largely unfenced and horses were “almost the only affordable” form of transportation. Autos like Model Ts were unreliable, and the Highline “roads were gumbo soil and for the early autos nearly impassable in bad weather.” Powerful work horses, mainly Percherons, did much of the heavy labor when the Etchart crew engaged in “farming, haying, feeding, freighting, sheep camp tending, and moving.” Horses pulled the machines used in haying, including mowers, dump rakes, bull rakes, and stackers. But by the time Gene was in his teens, John Etchart had purchased Farmall gasoline-powered tractors for mowing; two of the Farmalls replaced fourteen horse-drawn mowers. A few years later, Gene recalls, when the self-propelled swather appeared on the scene, “one man operating it replaced the two tractor mowers and that man had time left over to help with other jobs such as irrigating etc.” Gene goes on to note that, in the 1940s, as the pace of mechanization increased:

It didn’t all happen simultaneously. The self-propelled baler made the pitchfork obsolete but didn’t provide a way to pick up the bales. Leonard [Gene’s brother and the family’s most accomplished inventor] and Melford Arrotta designed and built [a] portable bale elevator.[25]Gene Etchart, The John and Catherine Etchart Famly Album, 38, Photo Insert #24.

When the Etcharts weren’t able to purchase or invent the technology they needed, they looked elsewhere for worthy innovations. For example, in the late 1930s, John Etchart sent his sons to the Big Hole Valley in western Montana to copy the design of the beaverslide hay stacker, a 30-foot-tall wooden ramp using a horse-powered basket to move hay to the top of a stack (thereby making much taller stacks possible). Developed in the Big Hole in the first decade of the twentieth century, the beaverslide stacker would find favor in seven western states and in Canada’s prairie provinces.

While in the Big Hole, the Etcharts also learned how to convert a truck into a gasoline-powered buckrake to pile hay into mounds. A buckrake, with teeth 7 to 9 feet long, can be as much as 5 feet high and 14 feet wide. The Etchart gas-powered rake differed from its Big Hole cousins in that it was powered by a Model A Ford truck whereas in the Big Hole ranchers tended to use “old, big automobiles like Cadillacs,” which proved too lightly constructed for the heavy work. This was a “simple and logical improvement,” typical of the Etchart ingenuity. During the period when they used only horse-drawn buckrakes, the Etcharts needed twenty-two of them, driven by twenty-two men and powered by seventy-five horses. Today, Gene points out, “To do the same job . . . needs three very expensive machines and three good men to operate them.”[26]Ibid., Photo Inserts #25, 27.

Although the Etcharts continued to use saddle horses until they sold their ranches recently, they found that “trail bikes and three wheelers cover a lot more ground without getting tired than do saddle horses.” But it was another form of technology that truly revolutionized ranching on the Highline.[27]Ibid., 40.

Aviation

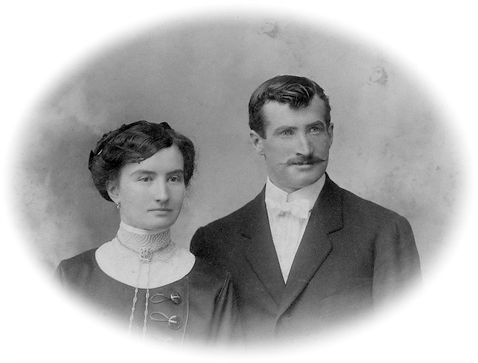

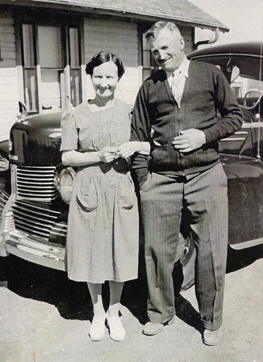

Catherine and John Etchart with their two flight-instructor sons, Mitch (left) and Gene, and Gene’s wife Elaine, in the winter of 1942-43.

Gene Etchart began flying in the late 1930s, and he soon extended his enthusiasm for aviation to other Montanans through the government-sponsored Civilian Pilot Training (CPT) flight schools he and others ran in Havre, Glasgow, and Miles City prior to World War II. Gene took his first flying lessons in 1936 and first soloed the following year. By 1940, he was running the Havre flight school and training scores of aspiring Montana fliers. As a boy, Gene recalls, “airplanes always fascinated me. They were out of reach, almost magic, a challenge and represented the object of a young boy’s fantasy.” At the same time, he wondered if airplanes could be useful in the operation of a ranch, and quickly answered his own question: “Being astride a tired saddle horse a long way from camp . . . sure made a weary cowboy wish he were on an airplane that seemed to travel distance so effortlessly.”[28]Pat Gudmundson, Gene Etchart, and Orval Markle, A Flying Start in the Big Sky (Miles City, MT: Star Printing Company, 1998), 72.

With the start of the Second World War, Gene and his brother Mitch Etchart (who had followed his older brother into the air in 1940) took their pilot-training skills to California, where they signed on as civilian instructors in an Air Corps contract flight school. The brothers enlisted in the Army Air Forces Reserve Corps, but on 17 April 1943, before Gene could receive his commission, he learned that his father John had suffered a fatal heart attack. As the eldest Etchart son, Gene was called back to Montana to run the ranch, an essential occupation in wartime.

Gene did not give up flying. Rather he applied it to ranch work and trained his sons, “plus a daughter-in-law,” as pilots, too. In fact, as of this writing (late 2007), just before his 91st birthday, Gene continues to fly. On the ranch, Gene mostly flew Cubs and Aeroncas, and he and the other Etchart pilots found the little planes to be a great help. In a recent interview, Gene recalled that, during winter in the early days, his father and a team of horses would head out to inspect the Etcharts’ sheep camps (“there might be ten of them”) in the Missouri Breaks. It would “take him a week or even ten days to make the circle of all those camps.” After John’s death, the younger aviator Etcharts—using planes with skis—could “visit every one of those camps and be back in Glasgow for lunch.” The planes not only increased efficiency, but they also allowed the Etcharts to keep a better eye on their domain. If a hunter left a gate open or spring runoff damaged a fence, they could land the plane and make repairs or let their hands know about the problem. “We used our planes like they were pickups,” Gene says. He recalls that when he started using “our small Aeronca plane to scout far and wide over range lands to spot cattle,” the foreman on the Etcharts’ North Ranch, Bud (Lloyd) Burger went along as a spotter and nicknamed Gene’s plane ‘the High Loping Buckskin’.” Gene notes that Bud Burger was a “dyed-in-the-wool cowboy,” who professed that “anything you couldn’t do horseback wasn’t worth doing,” and yet he grew enthusiastic about the plane’s “untiring range and ability to scope a lot of country in a short time.” Burger would frequently call Gene for “what he called air support.”[29]G. Etchart, Newby interview; Gene Etchart, The John and Catherine Etchart Famly Album, 40. See also Jim Gransbery, “Rancher’s Passion for Aviation Spans 7 Decades,” Billings … Continue reading

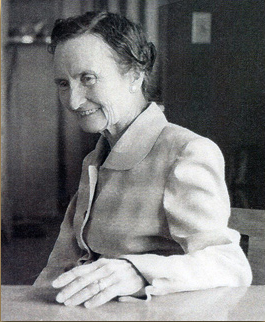

Catherine Etchart: Ranch Matriarch

Although her husband contributed mightily to the success of the Etchart ranching enterprise, Catherine Urquilux Etchart played an equally central role in building, and sustaining, the ranch. As historian Jeronima Echeverria has written, Catherine—like many Basque women—was “particularly adept at eschewing traditional female roles when necessary.” Immediately upon her arrival in Montana, Echeverria goes on, Catherine:

began learning to work a ranch, including butchering and salting meats, preserving fruit, washing clothes by scrubboard, fencing pastures, and raising a vegetable garden, as well as four sons. Despite John’s protestations that she was working too hard, and the fact that he had hired a cook, Catherine took her place at the stove alongside the hired girl.[30]Jeronima Echeverria, Ph.D., “Basque Pioneer Women,” in Amerikanuak: Basques in the High Desert, ed. Robert G. Boyd (Bend, OR: The High Desert Museum, 1995); see … Continue reading

In a moving tribute to Catherine in Montana The Magazine of Western History, Basque-American scholar Monique Laxalt Urza notes that, despite her husband’s desire to release her from “working too hard,” Catherine continued—throughout her long life—to rise at five-thirty:

to have the ranch hands’ breakfast on the table by six-thirty, spending the morning hours at housework, helping the cook in the preparation of the noon and evening meals, tending her garden, canning her fruits and making her wine. As so many women of the day, she claimed that recreation was a foolish waste of time. In the evenings she took long walks in the country, alone or with a little ranch dog.

After John died, Catherine never moved into town from the irrigated place at Tampico, and when her many grandchildren would visit, “her idea of entertaining them was to have them work alongside her as she prepared the meals, cleaned the house, tended to her chickens and to her garden.” Gene recalls that his mother was deeply religious, “solid and conservative in her Christian beliefs.” When her granddaughters would marry, she wrote each of them the same note: “Love has no boundaries. You delight in doing things for each other, being kind. I crossed the ocean confident in my beloved. I never regretted it.”[31]Monique Laxalt Urza, “Catherine Etchart: A Montana Love Story,” Montana The Magazine of Western History, Winter 1981, 15, 17.

Upon her death at age 90 in 1978, Catherine Etchart left behind a remarkable legacy. She could no doubt concur with what her husband John had written forty years earlier, when they were briefly apart while John had minor surgery: “We can be satisfied with our past, we have accumulated a ranch and livestock which will keep us and our family from the poor house if we just give them the chance.”[32]Ibid., 14, 17.

Largely Unchanged?

When we visit the cities along the course of Lewis and Clark’s journey, whether they be St. Louis, Omaha, or Great Falls, we have little difficulty in imagining the dramatic changes that these urban places have undergone over the last two centuries. And yet, on the Upper Missouri, where the place, as Gene Etchart says, “is largely unchanged” (at least at first glance), the changes have been less obvious perhaps, but no less remarkable. Just as ranching brought fences and new water sources, cattle and sheep in lieu of bison, and machines that transformed human relationships to work and the landscape, so too would a next wave of settlement, the coming of the homesteaders, alter this place irrevocably.

Note: I wholeheartedly thank Terrell and Ed Newby and the extended Etchart family, especially Gene Etchart and his wife Elaine, Joe Etchart, and Paulette Etchart & Jon Satre, for their generosity and insight and deep knowledge of ranching in northeastern Montana. My gratitude, too, to Barb Cosens, Moscow, Idaho, and Susan Cottingham and Joan Specking of the Montana Reserved Water Rights Compact Commission staff for smoothing my way.

Notes

| ↑1 | Conrad Kohrs, Conrad Kohrs: An Autobiography (Polson, MT: privately printed, 1977), 80, 99. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Emory Cecil Newby,” Progressive Men of the State of Montana, Illustrated (Chicago: A. W. Bowen & Company, ca. 1901), 1744. |

| ↑3 | Arthur Davenport Newby, “Early Days in Montana,” Montana Farmer-Stockman, 15 May 1955. |

| ↑4 | Ibid. |

| ↑5 | Terrell C. Newby, unpublished poems and prose, courtesy of Terrell Newby, Seattle, WA. |

| ↑6 | “Incidents in the Lives of the Emory and Margaret Newby Family in the Early Days of Chinook in Montana Territory (as told to a reporter),” publication name, location, and date unknown, courtesy of Terrell Newby, Seattle, WA. |

| ↑7 | Gene Etchart, interview with the author, Glasgow, MT, 22-23 October 2006 (hereafter G. Etchart, Newby interview). An excellent interview with Gene Etchart by Brian Kahn, Home Ground Radio, was broadcast on Yellowstone Public Radio, 26 December 2006. |

| ↑8 | Barbara Cosens, conversation with the author, Helena, MT, summer 2006. |

| ↑9 | Ibid., 42, 41. |

| ↑10 | G. Etchart, Newby interview. |

| ↑11 | Ibid. |

| ↑12 | Gerald D. Nash, The Federal Landscape: An Economic History of the Twentieth-Century West (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999), 32. |

| ↑13 | Gene Etchart, “Some of the Impacts of Federal Legislation and Programs in the Milk River Country of North Central Montana,” unpublished manuscript. |

| ↑14 | Gene Etchart, The Way It Was, 45. |

| ↑15 | Quoted in Robert S. Fletcher, “That Hard Winter in Montana, 1186-1887,” Agricultural History, Vol. 4, No. 4 (October 1930), 124; original source for quote was Weekly Yellowstone Journal (Miles, City, MT), 23 October 1886. |

| ↑16 | Fletcher, “That Hard Winter,” 125; Fletcher’s source was again the Weekly Yellowstone Journal, various issues in January, February, March,and April 1887. |

| ↑17 | Quoted on “The Cowboy Poetry of Charlie Russell’s Stagecoach” website, www.charlierussell.org/lastofthe5000.htm |

| ↑18 | Fletcher, “That Hard Winter,” 130. |

| ↑19 | Gene Etchart, “Hard Winters,” The John and Catherine Etchart Famly Album (Glasgow, MT: privately printed, 2007), 32-33. |

| ↑20 | Ibid, 33. |

| ↑21 | Ibid. |

| ↑22 | Ibid, 34. |

| ↑23 | Ibid. |

| ↑24 | E. G. Nourse, “Some Economic and Social Accompaniments of the Mechanization of Agriculture,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 20, No. 1, Supplement, Papers and Proceedings of the Forty-second Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association. (Mar. 1930), 129, 118. |

| ↑25 | Gene Etchart, The John and Catherine Etchart Famly Album, 38, Photo Insert #24. |

| ↑26 | Ibid., Photo Inserts #25, 27. |

| ↑27 | Ibid., 40. |

| ↑28 | Pat Gudmundson, Gene Etchart, and Orval Markle, A Flying Start in the Big Sky (Miles City, MT: Star Printing Company, 1998), 72. |

| ↑29 | G. Etchart, Newby interview; Gene Etchart, The John and Catherine Etchart Famly Album, 40. See also Jim Gransbery, “Rancher’s Passion for Aviation Spans 7 Decades,” Billings Gazette, 27 November 2007; http://www.billingsgazette.net/articles/2007/11/27/news/state/18-flyingcowboy.txt |

| ↑30 | Jeronima Echeverria, Ph.D., “Basque Pioneer Women,” in Amerikanuak: Basques in the High Desert, ed. Robert G. Boyd (Bend, OR: The High Desert Museum, 1995); see www.sde.idaho.gov/InternationalEducation/docs/Basque/BasqueWomen.pdf |

| ↑31 | Monique Laxalt Urza, “Catherine Etchart: A Montana Love Story,” Montana The Magazine of Western History, Winter 1981, 15, 17. |

| ↑32 | Ibid., 14, 17. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.