Lewis is likely at Big Bone Lick collecting ancient bones for President Jefferson.[1]No known record provides the exact dates Lewis was at Big Bone Lick. We do know he was in Cincinnati on 3 October 1803, and that he had left Big Bone Lick before Thomas Rodney arrived there on 10 … Continue reading Fellow traveler Thomas Rodney and scientist Caspar Wistar describe bones from there that resemble the American bison—the latter collected by William Clark in 1807.

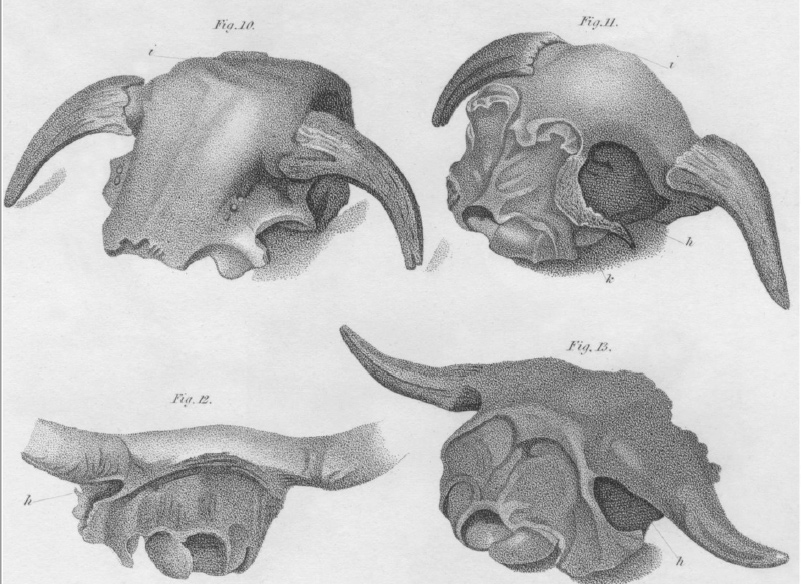

Above: the first two are specimens collected by William Clark at Big Bone Lick in 1807. The bottom row, an ox and buffalo, were used by Caspar Wistar for comparison.

Ancient Bones

As to the bones found at these places most of those now there are only buffelo bones. This no doubt was there last resort when they were sick; and here they died and left their bones which sunk into the mud.

—Thomas Rodney (10 October 1803)[2]Dwight L. Smith and Ray Swick, ed., A Journey Through the West: Thomas Rodney’s 1803 Journal from Delaware to the Mississippi Territory (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1997), 112–13.

Deep Wells

The main spring at the uper salt works boiled up to the sufface of the ground and fell into the salt wells they had dug around it, which were only 4 or 5 feet deep at the lower works. There was several large wells 10 or 12 feet deep.

—Thomas Rodney (10 October 1803)[3]Ibid., 113.

Clark’s 1807 Visit

In an 1818 paper addressed to the American Philosophical Society, Caspar Wistar examined two skull types from specimens collected at Big Bone Lick by William Clark in the fall of 1807:

The two heads which are the subjects of the following observations, were selected from a large number of bones presented to the society by our much venerated President Jefferson. Being satisfied that the morass near the falls of Ohio, called the Big Bone Lick, still contained many animal remains which were worthy of attention, he engaged General Wm. Clarke, who is so honourably known to the world by his Journey to the Pacific Ocean, to explore it, and furnished him with all the means necessary for so expensive an undertaking.

Gen. Clarke accomplished the business committed to him with great promptitude, and procured several large boxes of bones.-

By comparing the Big Bone Lick specimens collected by Clark, (see figure, top row) with that of the common ox, Wistar concluded, “Was not this animal nearly allied to the bison?”[4]Mr. Jefferson, and Caspar Wistar. “An Account of Two Heads Found in the Morass, Called the Big Bone Lick, and Presented to the Society, by Mr. Jefferson.” Transactions of the American … Continue reading

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to October 6, 1803:

Notes

| ↑1 | No known record provides the exact dates Lewis was at Big Bone Lick. We do know he was in Cincinnati on 3 October 1803, and that he had left Big Bone Lick before Thomas Rodney arrived there on 10 October. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Dwight L. Smith and Ray Swick, ed., A Journey Through the West: Thomas Rodney’s 1803 Journal from Delaware to the Mississippi Territory (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1997), 112–13. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., 113. |

| ↑4 | Mr. Jefferson, and Caspar Wistar. “An Account of Two Heads Found in the Morass, Called the Big Bone Lick, and Presented to the Society, by Mr. Jefferson.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 1 (1818): 375-80. doi:10.2307/1004925. |