Robert Hunt retired from Seattle Trust & Savings Bank in 1987 after 40 years of service. Bob has “trod” his own way along part of the Lewis and Clark story, having spent boyhood near the Missouri River, at St. Joseph and Kansas City, and studied in Philadelphia where he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania—all these places having figured in the expedition. He contributed many articles to We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation.

Contributions

Lewis and Clark appear to have been unaware of the existence of Chinook Trade Jargon. Never-the-less, some of the words they encountered would be later documented as part of the jargon.

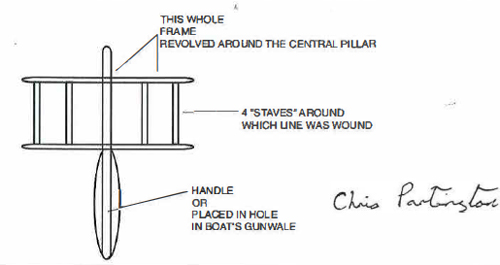

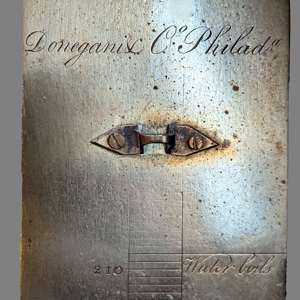

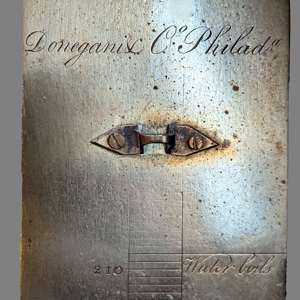

Lewis knew before embarking on his mission that there would be a pack of fish in his future. In Philadelphia in the summer of 1803, preparing for the expedition, he visited the “Old Experienced Tackle Shop” kept by George R. Lawton, a dealer in “all kinds of Fishing Tackle for the use of either Sea or River.”

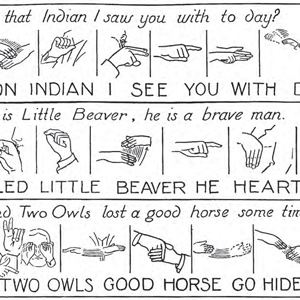

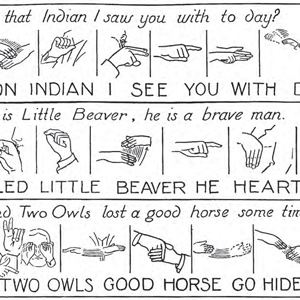

“our guide could not speake the language of these people but soon engaged them in conversation by signs or jesticulation, the common language of all the Aborigines of North America.” Lewis exaggerated the universality of sign language, which was mainly employed by tribes of the Great Plains.

Antoine Saugrain

by Robert R. Hunt

Called the “First Scientist of the Mississippi Valley,” Saugrain was a chemist and naturalist and the only physician in the frontier community of St. Louis when Lewis and Clark arrived there.

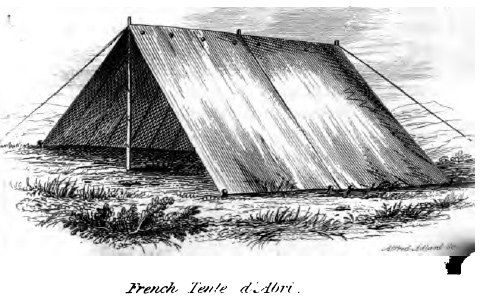

While in Philadelphia in the summer of 1803, Lewis clearly had foreseen the rigors of weather which would be encountered on a planned two year “campaign.” He carefully provided, as any military commander would, for appropriate protection for his soldiers.

The jolly men of Lewis and Clark danced their way into history—a fascinating look behind the “big scenes” of America’s intriguing Corps of Discovery.

Did they take on too much risk when they split into small groups on the way home? Did the Lewis and Clark Expedition actually fail?

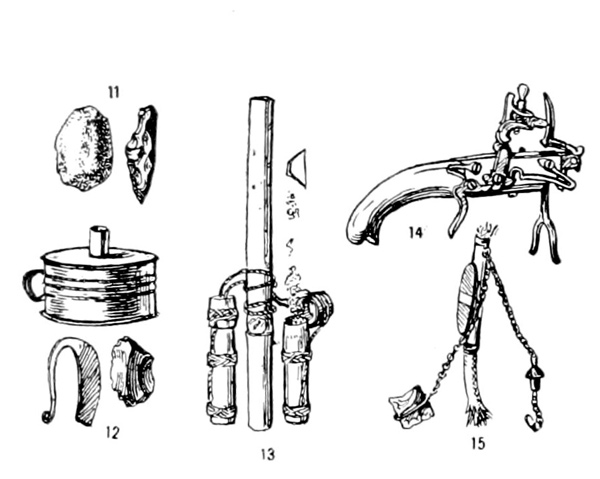

How did the Indians, expedition cooks, and the hunters make fire? Several methods were used.

The expedition left horse tracks of at least four to five hundred miles on a westward lineal course, plus at least a thousand miles easterly, widely scattered over strikingly varied terrain. The Corps of Discovery had become, in effect, a kind of cavalry unit.

Several anxious moments on the trail were associated with an implement which Lewis referred to in his journal as an “espontoon,” i.e., a half pike commonly carried by an eighteenth century infantry officer.

Thermometers and Temperatures

by Robert R. Hunt

President Jefferson held a long-term interest in climate and thermometers and recording climate data was included in his instructions to Lewis. Where Lewis obtained his thermometers and why the temperature on so many days days went unrecorded remains a mystery.

No military commander of the 18th-century would have thought of leading his troops on any mission without planning for liquor. In legislation and military orders of the day, the ration was typically expressed in “gills.”

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.