Figure 1

Plaster cast of the skull of Sergeant Charles Floyd

Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

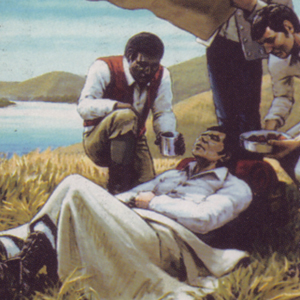

Before Floyd’s remains were sealed in the concrete core of an obelisk’s base, two plaster casts of the skull and jaw were made and photographed (Figure 1). One of the casts has long since been lost. The other, now in the Sioux City museum, served as the basis for a reconstruction of Floyd’s head by a forensic artist in 1997 (Figure 2), and placed on a specially designed and suitably uniformed mannequin that is now on display in the Sergeant Floyd Riverboat Museum.

Figure 2

Reconstruction of Sergeant Floyd’s Facial Features

by forensic artist Sharon Long[1]V. Strode Hinds, “Reconstructing Charles Floyd,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 27, No. 1 (February 2001), 16-19. See also James J. Holmberg, “Monument to a y’oung Man of Much … Continue reading

Courtesy, Sergeant Floyd Museum and Welcome Center at Sioux City

Charles Floyd, born in 1782, was the only one of the expedition’s famed “Nine Young Men from Kentucky” who actually was born there. He was a cousin of another expedition member, Sergeant Nathaniel Pryor, and may have been remotely related to William Clark. On 11 August 1803, 21-year-old Charles enlisted in the Corps of Discovery direct from civilian life. As an infantry officer prior to his retirement in 1796 on grounds of poor health, Captain Clark had developed the ability to recognize the potentials of his recruits, and he immediately began to systematically groom Floyd as a soldier.

Young Charles was a quick study. On 20 February 1804 Lewis placed him in charge of the officer’s quarters during their absences in St. Louis, and added: “the commanding Officer hopes that this proof of his confidence will be justifyed by the rigid performance of the orders given him on that subject.” In April 1804 he was promoted to the rank of sergeant.

Floyd began his journal on 14 May 1804, the day of the expedition’s departure from Camp Dubois, and with occasional advice thereafter from his captain, faithfully entered in it his brief, often fragmentary but usually pointed memoranda.

On 30 July 1804, Clark noted that Sergeant Floyd was “verry unwell a bad Cold & c,” and the next day Floyd himself admitted, “I am verry Sick and Has ben for Somtime but have Recoverd my helth again.” Meanwhile, the captains were preoccupied with the pursuit and punishment of a deserter, Private Moses Reed, and diplomatic relations with the Oto people. On 18 August 1804, Floyd wrote his last entry, emphasizing that “the Grand Chief of the ottoes” had arrived in camp. That same day, Clark reported that Floyd was “dangerously ill,” and that every man was attentive to him, especially Clark’s black servant, York. Shortly after noon on the 20th, Charles Floyd died “with a great deal of composure.”

Today it is generally agreed that he probably suffered a ruptured appendix, with resultant peritonitis. The captains tried every treatment they knew of, unaware that even the most advanced medical care of that day would not have saved his life.

“We carried him to the top of a bluff,” Clark wrote, “below a small river to which we gave his name and he was buried with the honors of war, much lamented.” Lewis read the funeral service, and the men marked the grave with a cedar post bearing the sergeant’s name and date of death. Two days later the men elected Patrick Gass, originally a private in Floyd’s squad, to assume Floyd’s rank and post.[2]Many years later, when Patrick Gass was in his late 70s, he offered a wholly fictitious account of the cause of Floyd’s demise. On 19 August 1804, he said, Floyd “had been amusing himself … Continue reading

On the expedition’s return from the mouth of the Columbia River in early September 1806, the men paused to visit Floyd’s grave for a final farewell. Finding that it had been partly uncovered, they refilled it and restored the fallen wooden marker.

After the Expedition

In his official post-expedition report to Secretary of War Henry Dearborn, dated 7 January 1807, Lewis affirmed that Charles Floyd was:

a young man of much merit. His father, who now resides in Kentucky, is a man much rispected, tho’ possessed of but moderate wealth. As the son has lost his life while on this service, I consider his father entitled to some gratuity, in consideration of his loss, and also, that the deceased being noticed in this way, will be a tribute but justly due to his merit.[3]Private Floyd’s father, also named Charles, was a surveyor who moved from Virginia to the Falls of the Ohio in 1779-80 via Daniel Boone‘s Wilderness Road. Jackson, Letters,, 1:366.

Pvt. Floyd’s land allotment of 320 acres (half a square mile) in Adams County, Mississippi, was conveyed to his heirs, and in 1839 his sister, Mary Walton, sold it for $640. His heirs also received his salary in cash–$86.33⅓ for one year of service (August 1803-August 1804)–as a member of the Corps of Volunteers for North-Western Discovery.

Related Pages

Floyd’s grave became a conspicuous point and a historic shrine on the Lewis and Clark trail almost immediately after the expedition was over. The American artist George Catlin painted Floyd’s Bluff in 1832, with the original cedar marker still in place.

No military commander of the 18th-century would have thought of leading his troops on any mission without planning for liquor. In legislation and military orders of the day, the ration was typically expressed in “gills.”

Church in St. Charles

by Joseph A. Mussulman

On the first Sunday after leaving Camp River Dubois, Joseph Whitehouse wrote that some of the party “went to church, which the french call Mass, and Saw their way of performing &c.”

On 20 August 1804, the Corps proceeded thirteen miles, while young Floyd quickly grew worse. A little past noon they landed, and presently Floyd said, “I am going away.”

Two hundred years after the event, interpretive artist Michael Haynes explains how he created his painting “Hallowed Ground.”

Selected Journal Excerpts

December 16, 1803

Eight men from Tennessee

Samuel Griffith, a local farmer, visits camp at Wood River, and Clark sends Sgt. Floyd to Cahokia with letters for Lewis. In the evening, Drouillard arrives at Cahokia with eight new recruits.

December 21, 1803

Seven fat turkeys

The enlisted men continue to raise cabins at Wood River, and two hunters bring in several turkeys. In a letter dated 28 December, Lewis describes the nature of his work in Spanish controlled St. Louis.

March 1, 1804

Quarters and stores

At Wood River, Illinois, the day begins with sub-zero temperatures. While they are in St. Louis, the captains leave specific orders for Sgt. Floyd regarding quarters and stores.

April 7, 1804

Capt. Stoddard's ball

Clark, Lewis, and York travel to St. Louis to attend a formal dinner and ball hosted by Captain Amos Stoddard, new Commandant of Upper Louisiana. Sgt. Ordway is left in charge at Camp River Dubois.

April 12, 1804

Discipline problems

On this or the next day, Clark and the Army Commissary leave St. Louis with provisions for the men at winter camp. Also near this date, Clark summarizes the discipline problems encountered thus far.

April 18, 1804

Sending for Capt. Lewis

Sgt. Charles Floyd and Pvt. George Shannon leave Camp River Dubois with two horses to meet Cpt. Meriwether Lewis who is crossing over from St. Louis by boat. By afternoon, Lewis arrives at camp.

May 14, 1804

Leaving Camp River Dubois

Clark and most of the men leave winter camp at the River Dubois and begin their journey up the Missouri. Several enlisted men begin their journals while in St. Louis, Lewis makes final preparations.

May 26, 1804

New orders

The boats make about ten miles reaching the area of present-day Berger, Missouri. Lewis issues detachment orders dividing the enlisted men into three squads with specific directions for handling rations.

July 7, 1804

Frazer's sun stroke

As the men row and tow the boats up the Missouri. Pvt. Frazer is “Struck with the Sun,” and Sgt. Ordway is separated from the main party. They camp across from present St. Joseph, Missouri.

August 12, 1804

Rounding Snyder Bend

The boats travel around an eighteen-mile bend in the Missouri—present Snyder Bend. It can be crossed by land in less than a mile. In Sgt. Floyd’s mess, Pvt. Weiser replaces Pvt. Thompson as cook.

August 19, 1804

Otoe's council, Floyd's illness

During a council at Fish Camp near present Homer, Nebraska, speeches with the Otoes are exchanged, but they appear dissatisfied with their gifts. Sgt. Floyd becomes seriously ill requiring urgent care.

August 20, 1804

Burying Sgt. Floyd

The expedition stops near present Sioux City, Iowa to bury Sgt. Floyd with a full military ceremony. Elsewhere, Salcedo reports on several American expeditions in contested Spanish territory.

June 2, 1806

Managing horses

At Long Camp in present-day Kamiah, Idaho, a horse corral is made, and Lewis’s horse must be shot. Ordway brings in seventeen tainted salmon, and Drouillard returns with Sergeant Floyd‘s old tomahawk.

September 4, 1806

Floyd's grave

On a wet morning, the expedition sets out with ample tobacco and flour obtained from trader James Aird. They stop to visit Sgt. Floyd’s grave and camp early to dry out near present Dakota City, Nebraska.

Notes

| ↑1 | V. Strode Hinds, “Reconstructing Charles Floyd,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 27, No. 1 (February 2001), 16-19. See also James J. Holmberg, “Monument to a y’oung Man of Much Merit’,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 22, No. 3 (August 1996), 4-13. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Many years later, when Patrick Gass was in his late 70s, he offered a wholly fictitious account of the cause of Floyd’s demise. On 19 August 1804, he said, Floyd “had been amusing himself and carousing at an Indian dance until he became overheated and it being his duty to stand guard that night, he threw himself down on a sand bar of the Missouri, despising the shelter of a tent offered him by his comrade on guard, and was soon seized with the cramp cholic, which terminated his life” on the following day. Gass’s memory simply failed him, and he obviously saw no reason to check his own journal, in which he would have been reminded that, to begin with, Floyd was sick all night on the 15th. John G. Jacob, The Life and Times of Patrick Gass, Now Sole Survivor of the Overland Expedition to the Pacific, Under Lewis and Clark, in 1804-5-6 (Wellsburg, Virginia: Jacob & Smith, 1859), 43-44. |

| ↑3 | Private Floyd’s father, also named Charles, was a surveyor who moved from Virginia to the Falls of the Ohio in 1779-80 via Daniel Boone‘s Wilderness Road. Jackson, Letters,, 1:366. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.