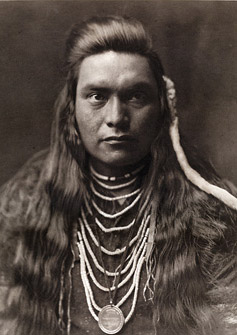

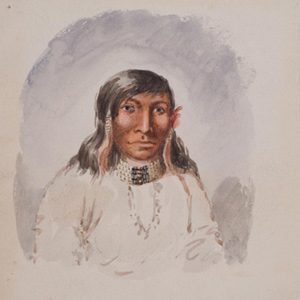

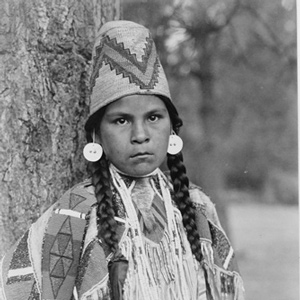

Lawyer, Nez Perce (1905)

Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952)

Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana.

The man in this portrait, wrote photographer Edward Curtis, “is a member of the family of that Lawyer who played a prominent role in Nez Perce affairs in the years following the treaty of 1855.” This man’s ancestor, the first “Lawyer”–so-nicknamed by white men in recognition of his persuasive eloquence and keen mind–was Aleiya, the son of Lewis and Clark’s friend, Twisted Hair. While negotiating the treaty of 1855, Governor Isaac Stevens declared him a “head chief,” over the objections of other acknowledged leaders of the tribe. Whites also renamed the Nez Perces’ Commearp Creek after him.

Sahaptian is a Plateau Penutian tongue; some scholars include Klamath-Modoc in the group, while others note only a close resemblance. The larger Penutian language family ranged from northern California across Oregon and north to Washington’s Columbia Plateau.

When Clark met the Nez Perce on Weippe Prairie in September 1805, he found “their dialect appears verry different from the . . . Tushapaws [Salish] although origneally the Same people,” but did not give his source for this incorrect information.

From The Dalles, Sahaptian (also Shahaptian) languages extended eastward to the Rocky Mountains. Speakers of these languages met by the Corps included the Walla Wallas, Klickitats, Teninos, Umatillas, Yakamas, Wanapums, and Nez Perces.

Sahaptin Peoples Encountered

The Walla Wallas

Walla Wallas, sometimes Waluulapam and sometimes on this site as Walula, are a Sahaptin-speaking indigenous people that lived primarily along their namesake river. There has been disagreement among historians regarding the nation’s etymology.

The Wanapums

Lewis and Clark called them “Sokulks” but they were ‘river people’ from the Sahaptin wána (river) and pam (people). Wanapam is an alternate spelling.

The Yakamas

The Yakama’s first Euro-American contact was the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. The captains named the people Chim’-nah-pum’ which was the name of the village at the mouth of the Yakima River.

The Teninos

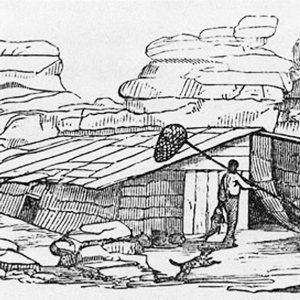

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Teninos lived on the north side of the Columbia River and controlled key fishing areas on the river’s south side. Tenino was a small village at Five Mile Rapids above The Dalles of the Columbia.

The Palouses

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Palouses had coalesced around four primary villages on the lower Snake River: Penewawa, Almota, Wawaiwai, and Palus. Lewis and Clark estimated their population as 2,300 which included Northern Nez Perce.

The Nez Perce

by Kristopher K. Townsend

First encountered September 1805 when John Colter met them on Lolo Creek near Travelers’ Rest, they would remain with the expedition in one way or another until 25 October 1805 saying their goodbyes at Rock Fort at The Dalles of the Columbia River. They were together again between 23 April 1806 and 4 July 1806, the expedition’s longest period of contact with any Native American Nation.

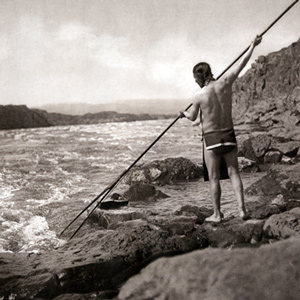

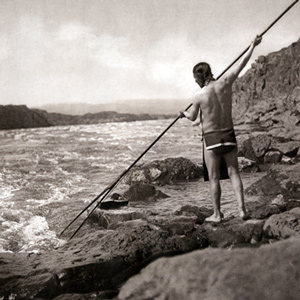

Life’s Cycle at the Dalles

by Barbara Fifer

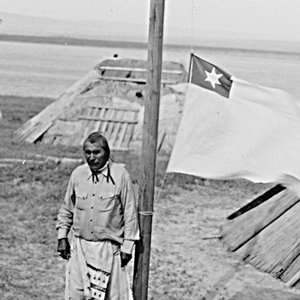

From the Columbia Plateau to the river’s mouth, people followed a yearly cycle for fishing, hunting, and harvesting wild foods. In the summer, people from many Sahaptin and Chinookan tribes visited The Dalles to trade and socialize.

The Umatillas

After emerging from the Wallula Gap on 19 October 1805, Clark came across some Umatillas hiding in their lodges, and he committed a serious faux pas by entering without permission.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.