On 9 September 1805, the Corps of Discovery turned west from the Bitterroot River up the stream they dubbed “Travelers’ Rest Creek,” and stopped a mile or so above its mouth at a heavily used Indian campsite on its south bank. In Paxson’s Travelers’ Rest, the artist portrays a meeting that took place the next afternoon.

“Lewis and Clark’s Camp at Traveler’s Rest, Lolo Creek 1805”

Oil on linen, 5½’ by 10′. Commissioned for the Missoula County Courthouse. Missoula County Art Collection, Missoula Art Museum. Photo © 2023 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

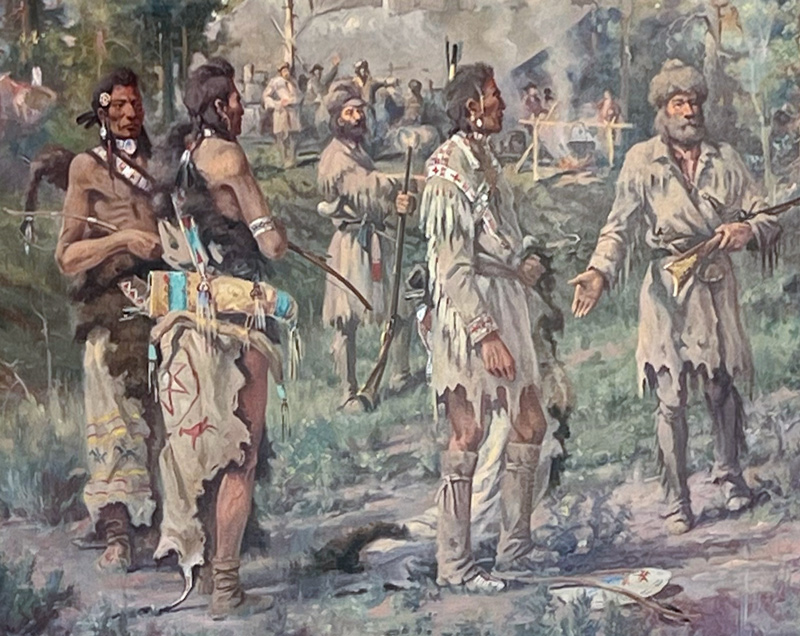

A Chance Encounter

Detail

Photo © 2023 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

George Drouillard, who is proficient in the common inter-tribal language of “signs or jesticulation”—known today as Plains Sign Language—is introducing to Captain Lewis three Nez Perce Indians whom Private John Colter met while hunting somewhere up the creek.[1]It was the Corps’ Lemhi Shoshone guide, Toby, who first engaged the three strangers in conversation “by signs or jesticulation, the common language of all the Aborigines of North America, … Continue reading Lewis extends the universal open-handed gesture of welcome. Afterwards one of the Indians, perhaps the best-dressed man, with a buffalo robe draped over his arm, will consent to join the Corps as a guide. However, he will grow impatient with their delay in departure on the 11th, and go on by himself, assuring them it will take only six days to cross the mountains. (Actually it will take them almost twice that long!) The mounted man beyond the oxbow in Travelers’ Rest Creek, at right, may be John Colter, leading one of the Indians’ fine horses to pasture with the Corps’ herd.

At Lewis’s right is Clark’s servant, York, dressed in blue as befitted a personal slave at that time. The Indian squatting at Lewis’s left hand is Toby, the Shoshone guide the captains had hired to lead them across the Bitterroot Mountains toward the Columbia River; he is displaying a map he has drawn for the captains with charcoal on deer skin. Behind Lewis, Captain Clark is apparently asking Sacagawea—who cradles her seven-month-old son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau—and her husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, whether they understand the strangers’ language. The young Shoshone woman’s averted gaze betrays her suspicion of these men from the Chopunnish nation, her peoples’ enemies.

Sometime before leaving Pittsburgh on 31 August 1803, Lewis paid $20—half of a captain’s monthly salary—for a “very active strong and docile” Newfoundland retriever he named Seaman. Paxson knew only that Lewis had a dog, but not its name, breed or appearance, since Lewis’s eastern journal had only recently been rediscovered and was not published until 1916. He has compromised by depicting a typical Indian dog like the ones described elsewhere in the journals.

Paxson’s Travelers’ Rest

Headgear worn by the Corps was one of the most problematic details in all 20th-century illustrations. Paxson’s good friend and fellow Montanan, Charlie Russell, solved the problem for most of those who followed him by topping the captains with broad-brimmed hats turned up into tricorns. That had been the official military style throughout the Revolution, and it remained popular with some civilians for a while afterward. But fashion statements will not tolerate restraint, and new styles were adopted by the end of the 18th century in both military and civilian life. Nevertheless, in the absence of adequate research into the Jeffersonian era—and notwithstanding the testimony of those anonymous drawings that appeared in some early reprints of Gass’s journal—the tricorn remained the hat of choice for artists until historian Robert Moore and artist Michael Haynes finally provided alternatives at the outset of the bicentennial observance.[2]Robert J. Moore, Jr., and Michael Haynes, Lewis and Clark Tailor Made, Trail Worn; Army Life, Clothing, & Weapons of the Corps of Discovery (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003), 166-85. In these two murals Paxson ignored the cliche of the tricorn and instead chose a style that had first appeared in Canadian paintings after 1825, a trimmed fur cap with ear-flaps turned up, and a stiff, narrow bill.[3]Michael Haynes, personal communication, 24 February 2005. Inexplicably, Paxson reverted to the tricorn for Lewis in his mural, “Lewis and Clark at Three Forks” (1912), for the Montana … Continue reading The enlisted men wear less formal hats of fur, resembling those often seen on late-19th-century paintings of mountain men; their G.I. hats, narrow-brimmed beaver-felt toppers with low crowns, were worn out and discarded by this time.

All members of the party were clad in buckskins and shod in moccasins from the time they left Fort Mandan. In the mural, details such as the generous lapels on the captains’ coats are Paxson’s compromises between the mountain-man look and military formality. All wore moccasins for the rest of the journey. It is not known for certain whether the captains still had boots to wear at this time, but they had other parts of their dress uniforms until at least the time they started home from Fort Clatsop.

Painting the Nez Perce

Detail

Photo © 2023 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The facts are not known, but it seems more than likely that Paxson owned a copy of Nicholas Biddle‘s edition of the Lewis and Clark journals, or more likely a reprint of it, for the History of the Expedition under the Command of Lewis and Clark was still a basic handbook for any serious traveler through the Northwest in the 1870s when Paxson set out for Montana. Of course, Reuben Thwaites’s edition of the complete journals, verbatim, had come out in 1904-5, and Paxson might have had access to that seven-volume collection also, but Biddle’s two-volume summary would have provided sufficient background for all the scenes he created.

The Corps’ Shoshone guide, Toby, “could not speake the language of these people, but soon engaged them in conversation by signs or jesticulation, the common language of all the Aborigines of North America.” Lewis continued, “it is one understood by all of them and appears to be sufficiently copious to convey with a degree of certainty the outlines of what they wish to communicate.”

In Paxson’s mural, George Drouillard has witnessed the Nez Perces’ explanations and is explaining to the captains that the three warriors are in pursuit of two Shoshones who have stolen 23 Nez Perce horses. The handsomely dressed Indian nearest to Drouillard has laid his bow and shield on the ground before him in a gesture of peaceful intent. His two wary companions, their riding-skins—in lieu of saddles—hanging from their waists, stand by with their quivers and bow-cases over their shoulders and their bows at the ready. Nearby, an armed soldier, perhaps John Colter, strikes a pose of relaxed watchfulness.

10 October 1805, Clark (Biddle’s paraphrase)

The Chopunnish or Pierced-nose nation . . . are in person stout, portly, well-looking men; . . . though the complexion of both sexes is darker than that of the Tushepaws [Salish]. In dress they resemble that nation, being fond of displaying their ornaments. The buffalo or elk-skin robe decorated with beads; sea-shells, chiefly mother-of-pearl, attached to an otter-skin collar and hung in the hair, which falls in front in two cues; feathers, paints of different kinds, principally white, green, and light blue, all of which they find in their own country; these are the chief ornaments they use. In the winter they wear a short shirt of dressed skins, long painted leggings and moccasins, and a plait of twisted grass round the neck.[4]Elliott Coues, ed., History of the Expedition under the Command of Lewis and Clark . . . . 1893 (Reprint, 3 vols., New York: Dover, 1965), 623.

17 May 1806, Lewis (Biddle’s paraphrase)

The Chopunnish themselves are in general stout, well formed, and active; they have high, and many of them aquiline, noses; the general appearance of the face is cheerful and agreeable, though without any indication of gayety and mirth. Like most Indians, they extract their beards; . . . The dress . . . consists of a long shirt reaching to the thigh, leggins as high as the waist, moccasins, and robes—all of which are formed of skins.

Their ornaments are beads, shells, and pieces of brass attached to different parts of the dress, or tied around the arms, neck, wrists, and over the shoulders; to these are added pearls and beads suspended from the ears, and a single shell of wampum[5]Sometimes the journalists’ use of wampum, a Northeast Indian loanword, denotes strings of beads used as a status symbol, for ceremonial exchange, or as currency. In this instance the … Continue reading through the nose. The head-dress of the men is a bandeau of fox or otter-skin, either with or without the fir, and sometimes an ornament tied to a plait of hair, falling from the crown of the head; . . . while the hair . . . falls in two rows down the front of the body. Collars of bears’ claws are also common. But the personal ornament most esteemed is a sort of breastplate, formed of a strip of otter-skin six inches wide, cut out of the whole length of the back of the animal, including the head; this being dressed with the hair on, a hole is made at the upper end, through which the head of the wearer is placed, and the skin hangs in front with the tail reaching below the knee, ornamented with pieces of pearl, red cloth, and wampum or, in short, any other fanciful decoration.[6]Coues, op. cit, 3:1016-17. In the original journals this description is found on May 13.

Paxson’s Historical Accuracy

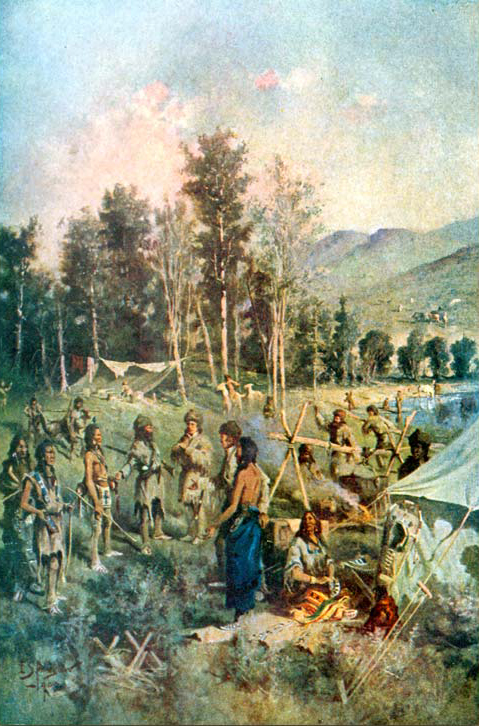

Frontispiece from The Trail of Lewis and Clark, Volume 2

E. S. Paxson, commissioned for Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

Titled “Lewis and Clark in Camp on Traveller’s[sic]-Rest (Lolo) Creek, Montana,” the original oil painting, which Paxson created in about 1900 for Olin Wheeler’s book, The Trail of Lewis and Clark[7]Two volumes; New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904., turned out to be a study for his 1913 mural (above). A few of the groupings and details are similar. Drouillard is introducing to Clark and Lewis the three Nez Perce he has just met. Toby wears a blue robe and carries a knife on his hip. At right is the captains’ tent (of Civil War design); York is at its door. Sacagawea is seated nearby; 7-month-old Jean-Baptiste sits next to a Plains-Indian style cradleboard. At left foreground is one of the company’s pack saddles.

On the whole, Paxson’s portrayals of the three Nez Perce men indicate that he had done his historical homework, at least to a limited extent. Among the obvious digressions from visual truth is that whereas Clark actually wrote that the Nez Perce were “Stout likely men,” Biddle transcribed Clark’s phrase as “stout, portly, well-looking men.” Indeed, the word “stout” is most often taken to mean “bulky in figure; thickset or corpulent,” but in Clark’s day its primary definition was “strong, valiant, brave, resolute.”[8]American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed., 2000). Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806). Thus Paxson’s lean and lithe figures might still have been stout men. More than likely he used some of his Indian friends, who might have included some Nez Perce, as models. Paxson did not show any of the Nez Perce men with pierced noses, even though Lewis observed that the practice was stylish in 1805 and 1806.

Paxson’s use of red in the trim of their clothing may add important highlights to the painting from a purely artistic viewpoint, but the color, it is said, would not be used decoratively by Nez Perce people, since red is symbolic of death—the faces of dead people are painted red before burial. Indeed, these men being in pursuit of Shoshone horse thieves, the one at far left has painted a large red spot on his forehead to show that he is prepared both to inflict and accept death.

Lewis emphasized (13 May 1806) that “the article of dress on which they appear to bstow most pains and ornaments is a kind of collar or brestplate” made of the skin of an otter hung with “whatever they conceive most valuable or ornamental,” including pieces of red cloth. That may be the article partly hidden behind the man at left. Each of the Indians is wearing a collar made not of bear claws but wampum—in this case, evidently dentalium shells—as a talisman.

The deep scallops on the extreme edges of the leather coats and shirts were caused by pegging the raw hides to the ground during scraping to remove the hair, and for brain-tanning to make the leather soft. They were sometimes left on in order to wick rainwater from the body of the garment. It has been suggested that the Indians’ shirts would have been neater in that detail than Paxson has shown.

The knee-high leggings on the principal Indian figure would have been suitable for an Indian of one of the midwestern woodland tribes, but not for a Nez Perce, who would have worn waist-high leggings. Finally, the designs in the decorative features of each of these men strongly hint at the use of small “seed-beads” such as are now associated with traditional Indian dress. However, seed-beads were not common among the Nez Perce until the 1850s.

It may be that Paxson’s divergences from Lewis’s accounts regarding Nez Perce appearance were based on an intimate knowledge of contemporary Indian culture and tradition, indicating that some fashions may have changed by the end of the 19th century. On the other hand, the oppressive treatment of Indian people, including the suppression of time-honored traditions, may have caused his informants to have lost much of their cultural recollections. Or, Paxson may have deliberately created a stylized “Indian” imagery to meet the expectations of his customers and viewers.

With assistance from Rob Collier, Native American Program Coordinator, Travelers Rest State Park.

Notes

| ↑1 | It was the Corps’ Lemhi Shoshone guide, Toby, who first engaged the three strangers in conversation “by signs or jesticulation, the common language of all the Aborigines of North America, it is one understood by all of them and appears to be sufficiently copious to convey with a degree of certainty the outlines of what they wish to communicate.” (Lewis, 10 September 1805.) |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Robert J. Moore, Jr., and Michael Haynes, Lewis and Clark Tailor Made, Trail Worn; Army Life, Clothing, & Weapons of the Corps of Discovery (Helena, Montana: Farcountry Press, 2003), 166-85. |

| ↑3 | Michael Haynes, personal communication, 24 February 2005. Inexplicably, Paxson reverted to the tricorn for Lewis in his mural, “Lewis and Clark at Three Forks” (1912), for the Montana state capitol building. |

| ↑4 | Elliott Coues, ed., History of the Expedition under the Command of Lewis and Clark . . . . 1893 (Reprint, 3 vols., New York: Dover, 1965), 623. |

| ↑5 | Sometimes the journalists’ use of wampum, a Northeast Indian loanword, denotes strings of beads used as a status symbol, for ceremonial exchange, or as currency. In this instance the “single shell of the wampum” probably refers to the small (1″ to 1.25″) “tusk shell” belonging to the order of molluscs called Scaphopods (scaff-o-pods, “shovel foot”). The American tuskshell, Dentalium spp., is a genus which once was plentiful along the Pacific Coast and was similarly valued as standard currency. Those “round bones which look like the joints of a fishes back” (Lewis, 21 August 1805), were also made into collars to be worn around the neck. See “Introduction to the Scaphopoda,” http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/mollusca/scaphs/scaphopoda.html (accessed 5 February 2005). |

| ↑6 | Coues, op. cit, 3:1016-17. In the original journals this description is found on May 13. |

| ↑7 | Two volumes; New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904. |

| ↑8 | American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed., 2000). Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.