Minuets of the Canadians (1807)

George Heriot (ca. 1759-1839)[1]George Heriot was born in Scotland in 1759, He emigrated to Quebec in 1792, and in 1799 became postmaster general of British North America. Heriot traveled extensively throughout Canada, producing … Continue reading

Etching and aquatint, handcolored with watercolor. National Archives of Canada, Ottawa (Accession No. 1989-479-3).

As part of his early education—a gentleman’s education—Thomas Jefferson learned to read music and to play the violin, and by age fourteen he was capable of writing down his favorite fiddle tunes. Many years later he recalled that as a young man he regularly practiced three hours a day. Unfortunately, he fractured his right wrist in 1786, and his playing was severely curtailed thereafter.

The large library of music he eventually collected, contained works by old masters such as Vivaldi (d. 1741), Corelli (d. 1713), and Handel (d. 1759), plus works by contemporary composers such as Carlo Campioni (1720-1788) and Joseph Haydn (1732-1809). In addition, there were books of popular songs, and a few volumes of psalms, hymns, and anthems.

During his lifetime he owned several violins, the finest of which may have been an Amati, made in Cremona, Italy in the 17th century.[2]Meriwether Lewis probably never heard his President play the violin, because Jefferson had fractured his right wrist in a fall, in Paris in 1786. Also, there were harpsichords, fortepianos and guitars in his household, but they were primarily ladies’ instruments.

While he was in Paris during the 1780s Jefferson may have purchased a bow by François Tourte (pronounced toort; 1747-1835), which represented a significant change in the mechanics of bow design, and has remained the accepted standard ever since. The inverted bend in the stick makes possible an even pressure between bow-hair and string through the whole stroke, which made it easier to play the long lyrical melodies and intricate, wide-ranging allegros of the music of Corelli and Haydn.

Thomas Jefferson’s younger brother, Randolph, who as a youth also studied the violin, was more inclined toward the vernacular idiom. According to Isaac, a family slave, Randolph “used to come out among the black people, play the fiddle and dance half the night.”[3]Isaac Jefferson, “Memoirs of a Monticello Slave,” in Jefferson at Monticello, ed. James A. Bear, Jr. (Charlottesville, Virginia, 1967), 22.

The Violin

In his first dictionary, published in 1806 while the Corps of Discovery was still on the road, Noah Webster defined violin in four simple words: “A sweet musical instrument.”[4]A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806; Facsimile, New York: Crown Publishers, 1970).

The violin evolved in Europe during the Renaissance (between about 1450 and 1600), in the vernacular (“popular”) musical tradition, to provide music for dancing, often out-of-doors. Early in the 17th century it became the mainstay of instrumental ensembles in the cultivated (“classical”) idioms, the opera and the sinfonia, which then were performed in the small private salons of the aristocracy. In the vernacular tradition the instrument retained its older name, fiddle; in the cultivated tradition it was called a violin.

It reached its first peak of general popularity in Western culture during the late 18th century. Around 1800, in the vicinity of just one southeastern German town, Klingenthal, eighty-five violin-makers (luthiers) produced an average of thirty-six thousand instruments a year, while a comparable number of cottage craftspersons produced strings and bows. Many other cities and towns throughout Europe were equally productive, and part of their total output was exported to North America for its relatively large number of dance musicians, and its less numerous but equally sincere devotees of the cultivated tradition.

Bows

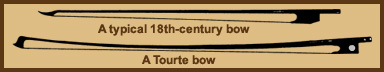

The stick of the bow Heriot’s fiddler is using is curved away from the bow-hair, rather than toward it, and is perhaps four inches shorter than the later Tourte bow. The 18th-century bow stick in the illustration at right is straight when the hair is loose. When it is tightened, either with the player’s right thumb or by means of a screw in the nut, the stick bends upward. The bow-hairs will then easily touch two or more strings at once, one or two sounding a “drone” pitch, while the remaining one carries the melody. It also means that the player must not use any vibrato in the melody because it would sound out-of-tune with the drones.

With the 18th-century bow the heaviest pressure on the string is in the center of the bow-hair, so that the middle of a long note or a melodic figure will be louder than the beginning or the end. Fiddlers did not play with the extreme ends—the point or the heel—of the bow, and the melodic style was connected rather than detached, for the bow seldom left the strings. A tune was played with an endless stream of up-and-down bowings, varying chiefly in repeated patterns of long and short up-and-down strokes. There were many different bowing patterns, comparable to regional speech dialects, such as the Georgia bow and the Tennessee half-shuffle.

Jefferson’s Favorites

One of Thomas Jefferson’s favorite compositions was the Sonata for Violin and Continuo, Opus 5, written by the famous Italian composer, Archangelo Corelli (1653-1713) in 1700. It consisted of a set of twenty variations on a graceful old Spanish tune called (in Italian) La Follia—pronounced la fo-LEE-ah, and meaning something like “A Madness,” presumably a musical definition of love.[5]The term sonata,from the Italian verb sonare, “to sound,” began to be used in the 17th century to refer to a composition for instruments, as opposed to a cantata, from the Italian verb … Continue reading

The well-thumbed and copiously annotated copy of the music in his library suggests that, at least prior to his wrist injury in 1786, Jefferson was capable of performing the difficult bowings required in many of the twenty elaborate variations of the simple theme.

Using a German-made instrument dating from the second half of the 18th century, as well as a modern violin such as Jefferson owned, violinist Samuel Taylor plays the theme and two of the variations from Corelli’s composition. He also discusses and demonstrates several differences between the styles of playing typically used by fiddlers such as Pierre Cruzatte in the vernacular tradition, and cultivated-tradition violinists such as Thomas Jefferson.

Three Demonstrations

Molto Expressivo

Mr. Taylor first demonstrates the expressive style of playing that Jefferson would have applied to the lovely theme. The expressive mood is established partly through the use of vibrato—moving the finger back and forth rapidly to impart a delicate wavering quality to each note. Expression is also heightened by subtle changes in loudness within the limits of each phrase—one of the advantages of the new Tourte bow. We may assume that Cruzatte would not have played expressively, as Jefferson would. He then shows us how Jefferson would have had to shift the position of his left hand up and down the fingerboard in order to execute one of the wide-ranging, ornate variations in Corelli’s composition.

You will hear Mr. Taylor use the the term with which Corelli’s era has been labled—Baroque (pronounced bah-ROHK)—an Italian word meaning “irregular in shape,” which refers to the elaborate ornamentation and embellishment that was typical of art, architecture, and music during the years between 1600 and about 1750. Probably, Cruzatte would not have shifted his left hand through as many different positions, for the music he played would not have required it.

Tuning Up

Mr. Taylor speaks of the difference between standard tuning in our own era, and standard tuning during Jefferson’s time. Jefferson would have checked the tuning of his harpsichord or piano using a tuning fork—a metal device invented in 1711 that was manufactured to vibrate with standard pitch when struck—then tuned his violin to match that of the keyboard instrument. Other instruments involved had likewise to tune to the keyboard instrument. Cruzatte, on the other hand, wasn’t a “team” or ensemble player, so matching a standardized pitch was unimportant to him. He undoubtedly would have tuned the strings of his fiddle to one another “by ear”—by listening to the intervals resulting from bowing adjacent strings—but he would cheerfully have tolerated at least slight differences in the overall tuning of his instrument caused by fluctuations in humidity or temperature.

Different Strokes

A variation of La Follia played with a modern bow held in the old-fashioned gamba manner. Jefferson would no doubt have used the gamba grip before he acquired his new Tourte bow in Paris. The new style of playing rapid notes with a “bouncing” bow required an overhand grip with a three-fingered fulcrum—thumb, middle finger, fourth finger—on the handle or “frog,” as demonstrated in the two previous examples.

Notice that Mr. Taylor is not using a chin rest. Until Jefferson received his first one, he would have braced the instrument against his neck or his collarbone. (Cruzatte would have braced his against his chest or, if his instrument were small enough, against the crook of his left arm.)

Recommended Reading

Sandor Salgo, Thomas Jefferson, Musician & Violinist. Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2000.

Helen Cripe, Thomas Jefferson and Music. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974.

Notes

| ↑1 | George Heriot was born in Scotland in 1759, He emigrated to Quebec in 1792, and in 1799 became postmaster general of British North America. Heriot traveled extensively throughout Canada, producing numerous scenic sketches and watercolors that were widely admired for their documentary value. He published a book, Travels through the Canadas, in 1808. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Meriwether Lewis probably never heard his President play the violin, because Jefferson had fractured his right wrist in a fall, in Paris in 1786. |

| ↑3 | Isaac Jefferson, “Memoirs of a Monticello Slave,” in Jefferson at Monticello, ed. James A. Bear, Jr. (Charlottesville, Virginia, 1967), 22. |

| ↑4 | A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806; Facsimile, New York: Crown Publishers, 1970). |

| ↑5 | The term sonata,from the Italian verb sonare, “to sound,” began to be used in the 17th century to refer to a composition for instruments, as opposed to a cantata, from the Italian verb cantare, “to sing,” which denoted a composition for voices. The word continuo stood for the accompaniment to the solo violin, which consisted of a keyboard instrument such as a harpsichord—or later, piano—plus a low stringed instrument such as a gamba. The word gamba (Italian for leg) is short for viola da gamba, a small bass viol of the Baroque Era that was placed between the player’s legs, like a modern cello. The bow was held with an underhand, palm-up grip. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.