Playing the Fiddles

© Michael Haynes, https://www.mhaynesart.com. Used with permission.

From beginning to end, the expedition is punctuated with dance. On the eve of departure upriver, at St. Charles, 18 May 1804, Private Joseph Whitehouse notes having “passed the evening verry agreeable dancing with the french ladies, etc.”[2]Whitehouse’s journal (Volume 7 of Original Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 1804-1806 edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites) Additional references from Whitehouse’s journal herein … Continue reading And, on arrival back home, on 25 September 1806, Clark reports, “payed some visits of form to the gentlemen of St. Louis. in the evening a dinner & Ball.” There are at least 27 separate dates mentioned in the journals when the men danced, but we know that there were many other occasions. On 30 October 1804, when newly arrived among the Mandans, Clark says the party “Danced as is verry Comm. in the evening . . .” And again on 31 March 1805, only a week before setting out from Fort Mandan, he writes: “all the party in high Sperits they pass but fiew nights without amuseing themselves danceing possessing perfect harmony and good understanding towards each other.”[3]The Journals of Lewis and Clark, edited by Bernard De Voto, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1953. References to quotations or passages from the journals by dates are from De Voto’s edition … Continue reading

Of the dancing noted in the journals, almost half of the occasions are in response to requests of the natives or their chiefs—among the Mandans, the Lemhi Shoshones, the Nez Perces, the Yakamas, the Skillutes, etc. These occasions often prompted reciprocal dances on the part of the natives, with the men of the Corps sometimes joining in the native dancing. Special dates (at least when outward bound) were celebrated by dancing: Meriwether Lewis‘s birthday (18 August 1804), Christmas, New Year’s, and July 4th.

There are less frequent mentions of dance during and after the winter on the Pacific. Did they dance in those quarters? Probably not much, if at all. Sickness, malnutrition, and weather must have dampened the will. As historian Bernard De Voto notes, the daily log from January through March 1806 reflects “the monotony of the life at Fort Clatsop” and bears the repeated refrain—”not any occurrences today worthy of notice.” But on Christmas morning 1805 they did at least manage to greet the captains at dawn by “a discharge of the fire arm[s] of all our party & a Selute, Shouts and a Song which the whole party joined in under our windows after which they retired to their rooms were chearfull all the morning.” No mention of dancing! There was nothing at that dreary time “to raise our Sperits or even gratify our appetites.”

The urge to dance, however, had not entirely subsided on the homeward road. We find the men dancing again near The Dalles. Clark notes on 16 April 1805, that a visiting chief “set before me a platter of onions . . . and we all eate of them” after which the natives requested the party to dance, “which they verry readily consented.” There was more dancing among the Walla Wallas, further up the Columbia. Especially striking is the colorful occasion on 28 April 1806, when some 250 natives of the “Chimnahpoms” and the “WallahWallahs” arrived at the party’s encampment and formed a half circle arround our camp where they waited verry patiently to see our men dance.” After the party obliged them, the Indians were inspired to do their own dancing—some 350 men, women, and children continued their performance until 10 p.m.

The next day, the Wallah Wallahs “insisted on our dancing this evening, but it rained a little, the wind blew hard, and the weather was cold, we therefore did not indulge them.” At least one other dance occurs on their eastward journey. On 8 June 1806, while waiting for their assault of the Bitterroot Mountains, “the party amused themselves in dancing.” Once the party was on the other side of the Divide, headed down river, there were no specific mentions of this “amusement” until the Welcome Home Ball at St. Louis. The closest thing to it occurs 14 September 1806, “a little below the lower [end] of the Kanzas Village.” Here they met a party ascending the Missouri and managed to come into a renewed supply of “sperits.” Clark reported that the men “received a dram and Sung Songs until 11 o’clock at night in the greatest harmoney”—apparently without breaking into dance, as so often had been the case when headed upstream.

A Reason to Dance

With this catalog of dance occasions, we see multiple reasons as to why the men danced. They danced first of all to amuse themselves, to relieve tension—in the same way in which soldiers on the march since the dawn of history have done.

Captains Lewis and Clark knew that music “makes the hearts of men glad;” and “Whereas men rarely attain the end, but often rest by the way and amuse themselves, not only with a view to the further end, but also for pleasure’s sake, it may be well at times to let them find a refreshment in music.”[4]Aristotle, Politics, Book VIII, Ch. 5 [1339b]. With this in mind, the captains took care to let their men “find refreshment.” On special occasions they aided and abetted good spirits by the issuances of “ardent spirits.” Many of the dance occasions coincide with such issuances on “celebratory” dates. e.g.:

18 August 1804: “Cap. L. Birthday the evening was closed with an extra gill of whiskey and a dance until 11 o’clock”

30 October 1804: “. . . gave the party a dram, they Danced . . .”

25 December 1804: “the men merrily Disposed, I give them all a little Taffia (rum) . . . Some men went out to hunt & the others to Danceing and continued until 9 o’clock PM when the frolick ended . . .”

1 January 1805: Sgt. Gass records that after the morning firearms salute, and two glasses of “good old whiskey”—”about 11 o’clock one of the interpreters and half of our people went up at the request of the natives to the village to begin to dance . . .”[5]Gass’s Journal by Sgt. Patrick Gass (Reprinted from the edition of 1811) with analytical index and an introduction by James Kendall Hosmer, Chicago, A.C. McCurdy & Co., 1904. Additional … Continue reading (see similar entries by Clark, John Ordway, and Whitehouse).

26 April 1805: (after reaching the Yellowstone) Lewis relates that: “We ordered a dram to be issued to each person; this soon produced the fiddle, and they spent the evening with much hilarity, singing and dancing, and seemed as perfectly to forget their past toils, as they appeared regardless of those to come.”

4 July 1805: Whitehouse’s journal—”towards evening our officers gave the party the last of the ardent spirits except a little reserve for sickness. We all amused ourselves dancing until 10 o’clock . . .”

Though the “spirits” had run out by this Independence Day, we know the impetus to dance had not. There are repeated incidents afterwards, particularly on “diplomatic” occasions, when the fiddle was produced and the men danced. The natives were always fascinated by this strange behavior of their visitors, and frequently requested, even insisted on performances. The ability to entertain in this way and divert possible animosity undoubtedly helped the captains achieve more peaceful transit through potentially hostile country.

Thus, with the Mandans on 1 January 1805, Clark accompanies some of the men up to the village: “my views were to alay some little miss understanding which had taken place thro jelloucy and mortification as to our treatment towards them. I found them much pleased at the Dancing of our men . . .”

And Lewis, following his crucial horsetrading “deal” with the Shoshones on 26 August 1805, gave directions (perhaps with some bravado under the circumstances) for “the fiddle to be played, and the party danced very merrily much to the amusement and gratification of the natives” He then confesses that “the state of my own mind at this moment did not well accord with the prevailing mirth as I somewhat feared that the caprice of the Indians might suddenly induce them to withhold their horses from us without which my hopes of prosicuting my voyage to advantage was lost.” The order of the dancing seems thus to have been given as an act of confident cheerfulness in consummating the “deal,” maybe like “whistling in the dark.” We may surmise that music and dance helped allay any danger of backtracking on the trade.

The violin and dancing also reinforce the captains’ diplomacy at the Short Narrows on the Columbia (The Dalles proper) October 24-26, 1805. The advice of the Chiefs who accompanied the Corps from above The Dalles indicated that “the nation below had expressed hostile intentions against [them, and] would certainly kill them; particularly as they had been at war with each other. . .” Clark reports that at this tense moment when the principal chief from below visited the Corps, the captains seized that “favourable oppertunity of bringing about a Piece and good understanding between this Chief and his people and the two Chiefs who accompanied us. He then adds, as if to cap and seal this negotiation: “Peter Crusat played the violin and the men danced which delighted the nativs, who Shew every civility toward us.” Clark must have been counting on the ability of music to bring out a civil and cooperative spirit among the Chiefs.

The Dance Team

The inference from the many Journal entries cited above ls that all of the party (with the possible exception of the captains and Sacagawea) participated in the dancing, but there are several specific participants identified by name. Clearly the most important for these purposes is the “principal waterman of the party, Private Pierre Cruzatte, who was also the principal musician. Cruzatte carried with him a fiddle, as it is generally called in the Journals, though occasionally referred to as a “violin.” We have the testimony of Lewis himself as to Cruzatte’s ability with the instrument. On 25 June 1805, at White Bear Island Camp near Great Falls, he notes: “Such as were able to shake a foot amused themselves in dancing on the green to the music of the violin which Cruzatte plays extremely well“[6]Elliott Coues, History of the Expedition of Lewis & Clark, vol. II, p. 390, N.8. Because of his French origins, we assume that many French Canadian folk tunes of the era made up a considerable part of his repertoire. He was the indispensable key figure ln the dance life of the party.

One other man, Private George Gibson, also provided music. On 19 October 1805, while encamped on the Columbia in view of Mt. Adams Clark reports that after 100 Indians brought presents of wood to the Corps “two of our Party, Peter Crusat & Gibson played the violin which delighted them greatly.” It appears that Gibson also carried a violin—the reference in Elliott Coues’s edition of the expedition narrative to this event, among one of the Salishan tribes, near the mouth of Umatilla River, quotes Lewis as follows: “the highest satisfaction they enjoyed was the music of two of our violins (Cruzatte’s and Gibson’s) with which they seemed much delighted.”[7]Ibid. Nicholas Biddle, in preparing the narrative of the expedition (published in 1814), says there were two violins. It is the assumption of Elliott Coues that the second violin mentioned by Biddle … Continue reading

There were other musical “instruments” among the paraphernalia of the Corps. Ordway’s journal discloses, under date of 1 January 1805: “carried with us a fiddle & a Tambereen & a Sounden horn.”[8]Milo M. Quaife (ed.) The Journals of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Sergeant John Ordway, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1916. additional references from Ordway’s journal are simply … Continue reading Doubtless the “tambereen” appeared at the dances for beating rhythm. Among the camp supplies purchased by Lewis at Philadelphia were “4 Tin blowing Trumpets.”[9]Original Journals. Reuben G. Thwaites, ed. 8 Vols. New York, 1904-1905.

Other persons coming into the dance spotlight are:

- Private John Potts, who is alleged to have “frequently called the figures for square dances.”[10]David Moffitt, Music and Dance on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, unpublished manuscript in the “Music and Dance” file, Fort Clatsop National Memorial, Oregon. Thanks to information … Continue reading

- York, Clark’s black servant who was a “star” on 1 January 1805, at the Mandan frolic. Clark wrote: “I ordered my black Servant to Dance which amused the Crowd Verry much, and Somewhat astonished them, that So large a man should be active etc etc.”

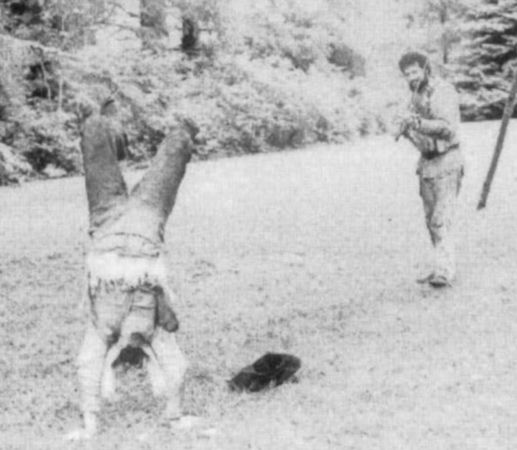

- Francois Rivet, a French engage. Though not a member of the Corps, he was with the party during the winter at Fort Mandan and is mentioned here as the Frenchman who, by Ordway’s report of the New Year’s celebration, “danced on his head and all danced round him for a short time then went into a lodge and danced a while . . .”

Sacagawea (though not necessarily her husband, Charbonneau) is believed to have been excluded from among the dancers of the party. This is based on the comments of the journalists with regard to the Christmas dance at the Mandan Village:

Gass wrote that the dance was “without the presence of any females except three squaws, wives to our interpreter, who took no other part than the amusement of looking on . . .”; and Whitehouse: “. . . all without the comp. of the female Sech . . .” Sacagawea presumably remained only a spectator of all the transcontinental dancing thereafter.

Whitehouse offers another group of potential dancers during the expedition. After watching the Shoshones do a “war dance” on 27 August 1805, Whitehouse wrote: “they tell us that some of their horses will dance but I have not seen them yet.”

Did the captains dance? It’s doubtful. Their entries almost invariably state that “the men amused themselves dancing,” not “we amused ourselves.” however, we must consider Gass’s report of 2 January 1805, in which he says that “Captain Lewis, myself and some others went up to the second village [of Mandans] and amused ourselves with dancing etc. the greater part of the day . . .” Somehow it’s difficult to think that “ourselves” was to include Lewis, or that the captains would ever have joined these frolics. The image we have of their military training, discipline and instincts as officers would seem to distance them, though we would not say this when thinking of the ceremonious “Balls” at St. Charles on the eve of departure or at St. Louis on their return. For those two occasions, we readily imagine one or the other of the officers joining in the civilities. But on the road? To express a guess: No . . .

We can imagine that (except for winter quarters and except for the staged performances before the natives) the dances were generally done spontaneously near a campfire in any kind of open space. At Fort Mandan, on Christmas day, Gass says “the men cleared out one of the rooms and commenced dancing.” Whitehouse’s entry for the same day says that after the morning flag raising and another glass of brandy “the men prepared one of the rooms and commenced dancing.”

Fisher’s Hornpipe

Music: “Fisher’s Hornpipe” played by Ralph Page’s Orchestra on Folk Dancer Label MII 1071.

The Dance from Griffith’s manuscript:

Cast off back, up again

Lead down the Middle, up again, and cast off one Co.,

Hands cross at Bottom, halfway, back again

Right and left at Top.

Modern-day translation: Couples 1 – 4 – 7 etc., active Do NOT cross over.

Active couples down the outside and back.

Active couples down the center with partner and back, cast off.

Right hand star with the couple below, left hand star back.

Active couples right and left four with the couple above.

Explanation:

Active couples turn out (man turns left, lady turns right) and walk down the outside of the set, behind their own respective lines, 8 steps in all.

Same couples turn toward the center of the set and walk up the outside of the set to original place.

Same active couples join right hands and walk down the center of the set, turn alone and, still holding right hands return to place. Cast off one couple. (Active man walks round second man who turns with him as the two turn as a couple to face the center of the set; the lady does the same with the second lady.)

Couples one and three make a right hand star and walk the star once around; same couples make a left hand star and walk it once around. Couples one and two right and left four. (The two couples pass through, passing partners right shoulder to right shoulder. 4 steps; the two men and the two ladies turn as couples with the active lady and the inactive man holding the pivot as they back around in place to face the center in 4 steps; again the two couples pass through as before in 4 steps; as before they turn as couples to face the center of the set in 4 steps.)

Continue the dance as long as desired.[11]“A COLLECTION OF THE NEWEST AND MOST FASHIONABLE COUNfRY DANCES AND COTILLIONS.” The Greater Part by Mr. John Griffith. Dancing Master in Providence, 1788. Said to be the first dance book … Continue reading

The Dance Step

Now we open the curtain on the more baffling and perhaps the most intriguing aspect of our subject. How did the men dance? What kind of dancing was performed? Although the journals do provide a wealth of detail about how the Indians danced, they tell us nothing specifically about how the expedition members danced. We have no “primary” sources: i.e. no journalist bothered to record what tunes were played or what steps were danced—nothing about the styles, figures and movements of the dancing. We are forced to guess and make inferences based upon likely secondary sources, such as the little we know of the men, their backgrounds, their origins, and the times and places in which they lived. In short, we must try to assemble such clues as we can—all in the hope that this may lead to further dialogue and study among expedition enthusiasts and dance students as to what likely was happening when, in Lewis’s phrase, the men “were able to shake a foot.”[12]Coues, Vol. II, p. 390, N.8.

The “young men from Kentucky” were no doubt conditioned to whatever dance habits they already had: i.e., to the rustic dance patterns of the frontier—patterns which were certainly less sophisticated than those found in New England, Virginia, or any more “civilized” part of the country. Ralph Sweet, a well-known student of American folkdance, reminds us that “at the time, Kentucky was the frontier, and didn’t have its dancing teachers, dance classes, much less music & dance publishing companies . . .”[13]Ralph Sweet, letter to author, July 27, 1987. such as those generally present back east. Mr. Sweet has tentatively suggested that on the frontier of that day, “it’s a pretty good bet that what they were doing is what is called “Big Circle” dancing, that is when they had a crowd together of both men & women.”

In the absence, however, of women dance participants on the expedition, some of the men would have had to do the usual women’s part under this scenario. On the other hand, if they did not indulge in dancing which typically called for both men and women, we might think that “probably what they did was an early form of clog dancing . . . called ‘Buck Dancing,’ ‘Hoedowning,’ or just plain ‘dancing.’ Mostly only men did it back then . . .”

That this is a reasonable first guess is corroborated by a leading authority on American folkdance, Kate Van Winkle Keller. On supposition that the men danced solely for their own entertainment, she writes “I strongly suspect that the form used would have simply been solo or duo jigs or hornpipes—i.e., stepping dances, the ancestors of today’s clogging.”[14]Kate Van Winkle Keller, Curator, Country Dance and Song Society of America, letter to author, September 11, 1987. But, Ms. Keller warns, all such opinion must be conjectural only, dependent upon more authoritative knowledge of where the men came from, their upbringing, their place in the community prior to military service, and similar background information.

Several of the dance episodes in the journals focus solely on Clark’s black servant, York, when Clark has him dance before the natives—apparently as a solo performer. It seems safe to assume that York would have done the “clogging,” jig type of movement mentioned above, to the accompaniment of Cruzatte’s fiddle.[15]For an interesting discussion of embellishments brought to English contra and square dances of the period by negroes on southern plantations, see Jerry Duke, Clog Dance in the Appalachians, Duke … Continue reading

But for the group dancing, we may have more insight by reviewing, as Ms. Keller suggests, what we know of the members of the Corps. These men were not “country bumpkins,” skipping around as in a Breughel etching! Though we have limited information about their upbringing, we see them in the journals as seemingly intelligent, resourceful young men, often with training in journeyman trades, comparatively literate for their times. With this background in mind we come to Lewis’s entry of 25 June 1805, at White Bear Island Camp near the Great Falls: all who “could make use of their feet had a dance on the green to the music of the violin.”[16]Coues. Lewis’s phrase here, “a dance on the green,” is an echo of the traditions and backgrounds of most of the men of the permanent party. According to Charles G. Clarke’s “biographical roster” of the members of the expedition,[17]Charles G. Clarke, The Men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, a biographical roster of the 51 members and a composite diary of their activities from all known sources, the Arthur H. Clark Company, … Continue reading most of them were either born or reared in families coming originally from Virginia, Pennsylvania, or a New England state, usually of Scotch, Irish, Welsh, or English background. As noted in The Country Dance Book, by Ralph Page and Beth Tolman, these areas grew from coastal settlements which had “experienced a constant injection of lusty immigrants fresh from dancing on their own village greens.”[18]Beth Tolman and Ralph Page, The Country Dance Book, (the Old-Fashioned Square Dance, it’s History, Lore, Variations and It’s Callers’ Complete & Joyful Instructions), Countryman … Continue reading Speaking of New England, particularly as representative of much of the United States during the post Revolutionary years, these writers declare:

If ever a people were given a chance to be born and bred in the purple of their dances, the Yanks were those people. As babies they were often lulled to rest to the measures of Speed the Plow or Smash the Window; and often they were carried to an assembly or junket where they were cradled in communal beds made from benches, seat to seat arrangement. Way before they were out or their swaddling clouts, then, these kids must have understood what was what on the dance floor. Then at an early age they began doing the dances themselves. During the revolutionary years everybody danced . . . the officers in both the English troops and the Colonials were so crazy about dancing that some say, if you listen hard enough, the hills of New England will give forth a faint echo of Lord Howe’s revels, or perhaps let go a few strains of Washington’s favorite, Sir Roger de Coverly.[19]Ibid., p. 13.

This tradition of “dancing on the green” may or may not have been ingrained so deeply in these young soldiers, most of whom were recruited in Kentucky or at other frontier military posts. But it is interesting that Lewis uses this particular phrase in describing their activity. We may cautiously assume then that at least some of the dancing of the Corps would have been reminiscent of the village dancing known to have occurred in the post Revolutionary War era of early America, i.e., 1788 to 1808.

Among the many publications and resource material of the Country Dance and Song Society (CDSS), one reference is especially pertinent in our guessing game about Lewis’s “village green.” Entitled A Choice Selection of American Country Dances of the Revolutionary Era 1775-1795,[20]Kate Van Winkle Keller and Ralph Sweet, A Choice Selection of American Country Dances of the Revolutionary Era 1775-1795, Country Dance and Song Society of America, NY, Second Revised edition, 1976. … Continue reading this collection contains 29 examples of music and dance figures drawn from manuscript sources and “represents as authentic a recreation as is possible of the way these tunes were played 200 years ago.” The text notes:

Country dances were the most popular of the social dances done by all ages and all classes of society in America during the latter part of the 18th century. They were basically English in origin, but were danced throughout the British Isles and parts of Western Europe as well. During the period . . . “country dance” was a generic term for progressive dances in longways formation, and did not have the connotation of rural or rustic dancing that the name may conjure up today. By the 1780s Americans began calling these dances contra dances, probably derived from the French term contredanse, and the two names for this type of dance, country and contra, coexisted well into the l9th century . . . The basis for choosing dances for this collection has been the frequency with which the dance names occur in the music and dance manuscripts of the period. Thus, these dances represent some of the most popular ones during and immediately following the American Revolution.

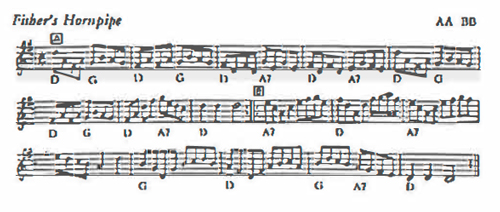

Since these contra dances are among the most popular ones during the period, we may surmise that Cruzatte and the men of the Corps would have become familiar in one way or another with some of them. One of the dances in this collection is called “Fisher’s Hornpipe.”[21]Ibid., p. 24. In his book Heritage Dances of Early America,[22]Ralph Page, Heritage Dances of Early America, Lloyd Shaw Foundation, Colorado Springs, CO, printed by Century One press, Colorado Springs, Co, 1976. Ralph Page gives us a detailed description of “Fisher s Hornpipe.” He notes that it “is found in more early American dance manuscripts than any other dance, so it must have been a popular dance. The tune is a popular one with fiddlers all over the country.”[23]Ibid., p. 18.

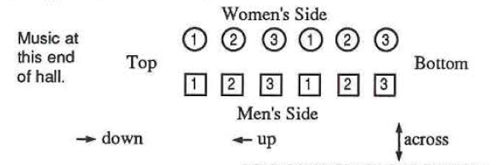

If then we can picture the figure of this particular dance and hear the tune which governs it, we may at last have a reasonably good idea of how the Corps danced. But first we must understand what a contra dance is. Literally, “a contra dance is a dance of opposition, a dance performed by many couples face-to-face, line-facing-line,”[24]Ibid., p. 9. such as:[25]Keller, Sweet, p. 11.

With the above sketch as a pattern, here is Ralph Page’s explanation of what happens in a “Fisher’s Hornpipe.”[26]Page, p. 18.

The Dance Music

And to be sure that we have the correct music for the above performance, here is the tune for Cruzattes’s fiddle:[27]Keller, Sweet, p. 24.

There you have the music and explanation of movements for a dance which in all likelihood may have been danced by the men of the expedition. Others like it may have been part of their regular routine. We are somewhat confirmed and reassured in arriving at this conclusion by the careful work done at present day Fort Clatsop National Memorial. There, under the leadership of Superintendent Franklin Walker and Chief Ranger Curtis Johnson, extensive efforts have been made in recent years to offer authentic demonstrations to visitors, which illustrate how music and dancing was a key to the success of the expedition. The “Music and Dance” file at Fort Clatsop,[28]Fort Clatsop National Memorial, Astoria, OR. The author gratefully acknowledges the helpfulness of Superintendent Franklin Walker, Chief Ranger Curtis Johnson and Jane Warner, Visitor Services, in … Continue reading compiled by Cynthia Wright, David Moffitt, and other associates, includes outlines of mini-skits and cassettes of fiddle music centered on this theme. In addition to “Fisher’s Hornpipe” annotated above, David Moffitt’s fiddle cassettes include such enticing selections as “Devil’s Dream,” “Soldier’s Joy,” “Fire on the Mountain,” “Whiskey Before Breakfast,” “Miss McCloud’s Reel,” “Boil the Cabbage,” and many other Scotch-Irish jigs, reels and hornpipes. To be sure, there are also included, with a bow to Pierre Cruzatte (pun intended), tunes with a French Canadian accent or origin, such as “Jolie Blonde,” “Old French Hornpipe,” and “La Belle Catherine.” The modern day Fort Clatsop people thus seem to have envisioned the men of the Corps in contra dance tunes and patterns on the basis of the same general line of reasoning which has been outlined above.

We come then at last to the end of this roundabout effort to track our men on their dance trail across the Great West. Not being able quite to catch up with them, our energies begin to flag. We see in the distance that the campfire burns low, the fiddle has been put to rest and the men fade from the scene. We close the journals on the dance chapters, imagining perhaps a bit more vividly what was happening on Lewis’s “green.” Hereafter, in our musings and re-enactments about the expedition, if we but watch and listen more carefully, we may readily see

“our young men break forth into dancing and singing, and we who are their elders dream that we are fulfilling our part in life when we look on at them . . . we delight in their sport and merrymaking, become able to awaken in us the memory of our youth.”[29]Plato, Laws, Book II [653].

Long may they dance with gusto and merriment in the life of the Republic!

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert R. Hunt, “Merry to te Fiddle: The Musical Amusement of the Lewis and Clark Party”, We Proceeded On, November 1988, Volume 14, No. 4, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol14no4.pdf#page=10. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Whitehouse’s journal (Volume 7 of Original Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 1804-1806 edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites) Additional references from Whitehouse’s journal herein are identified in the text of this paper simply by date. |

| ↑3 | The Journals of Lewis and Clark, edited by Bernard De Voto, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1953. References to quotations or passages from the journals by dates are from De Voto’s edition unless noted otherwise. Portions of quoted texts have been placed in italics by the author to emphasize their relation to the subject of this paper. |

| ↑4 | Aristotle, Politics, Book VIII, Ch. 5 [1339b]. |

| ↑5 | Gass’s Journal by Sgt. Patrick Gass (Reprinted from the edition of 1811) with analytical index and an introduction by James Kendall Hosmer, Chicago, A.C. McCurdy & Co., 1904. Additional references from Gass’s journal simply are identified in the text of this paper by date. |

| ↑6 | Elliott Coues, History of the Expedition of Lewis & Clark, vol. II, p. 390, N.8. |

| ↑7 | Ibid. Nicholas Biddle, in preparing the narrative of the expedition (published in 1814), says there were two violins. It is the assumption of Elliott Coues that the second violin mentioned by Biddle belonged to Private Gibson. As to the power and effect of the dancing and singing of the Corps, we are indebted to Sgt. Ordway for his incomparable description of the events of April 28, 1806. His entry for this date, in part, is as follows: . . . the Indians Sent their women to gether wood or Sticks to See us dance this evening. about 300 of the natives assembled to our Camp we played the fiddle and danced a while the head chief told our officers that they Should be lonesom when we left them and they wished to hear one of our meddicine songs and try to learn it and wished us to learn one of theirs and it would make them glad. So our men Sang 2 Songs which appeared to take great affect on them. They tryed to learn Singing with us with a low voice. the head chief then made a speech & it was repeated by a warrier that all might hear. then all Savages men women and children of any size danced forming a circle round a fire & jumping up nearly as other Indians, & keep time verry well they wished our men to dance with them So we danced among them and they were much pleased, and said that they would dance day and night until we return . . .” |

| ↑8 | Milo M. Quaife (ed.) The Journals of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Sergeant John Ordway, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1916. additional references from Ordway’s journal are simply identified in the text of this paper by date. See on this site Fiddle Music, Tambourine and Sounding Horn. |

| ↑9 | Original Journals. Reuben G. Thwaites, ed. 8 Vols. New York, 1904-1905. |

| ↑10 | David Moffitt, Music and Dance on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, unpublished manuscript in the “Music and Dance” file, Fort Clatsop National Memorial, Oregon. Thanks to information provided to the author by Superintendent Franklin Walker, Fort Clatsop National Memorial, it appears that the information about Potts’s role as a “caller” comes from Lewis and Clark Partners in Discovery by john Bakeless (New York, 1947). p. 268. Bakeless seems to have gotten his information from a manuscript of Nez Perce Indian statements collected by Mrs. Joe Evans, Sr. The manuscript is located in the Sacagawea Museum, Spaulding, Idaho. Bakeless writes: “The white men, as usual, danced for the Indians, whose modern descendants could still describe the scene in the 1930s. Potts – his monosyllabic name was easy for the redskins to remember – ‘he boss over mans how to do funny dance and sing songs, and all laugh.'” |

| ↑11 | “A COLLECTION OF THE NEWEST AND MOST FASHIONABLE COUNfRY DANCES AND COTILLIONS.” The Greater Part by Mr. John Griffith. Dancing Master in Providence, 1788. Said to be the first dance book published in the United States. |

| ↑12 | Coues, Vol. II, p. 390, N.8. |

| ↑13 | Ralph Sweet, letter to author, July 27, 1987. |

| ↑14 | Kate Van Winkle Keller, Curator, Country Dance and Song Society of America, letter to author, September 11, 1987. |

| ↑15 | For an interesting discussion of embellishments brought to English contra and square dances of the period by negroes on southern plantations, see Jerry Duke, Clog Dance in the Appalachians, Duke Publishing Co., San Francisco, 1984. York doubtless had his own variations of the clog type movements which could be imputed to his white, fellow voyagers on the expedition. For more on clog dancing, see also Annie Fairchild, Appalachian Clogging, what it is and how to do it, and Ira G. Bernstein, American Clogging Steps and Notation – Texts available from Country Dance and Song Society, Northampton, MA. |

| ↑16 | Coues. |

| ↑17 | Charles G. Clarke, The Men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, a biographical roster of the 51 members and a composite diary of their activities from all known sources, the Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale, CA 1970. |

| ↑18 | Beth Tolman and Ralph Page, The Country Dance Book, (the Old-Fashioned Square Dance, it’s History, Lore, Variations and It’s Callers’ Complete & Joyful Instructions), Countryman Press, NY, a.S. Barnes and Company, 1937; p. 12. |

| ↑19 | Ibid., p. 13. |

| ↑20 | Kate Van Winkle Keller and Ralph Sweet, A Choice Selection of American Country Dances of the Revolutionary Era 1775-1795, Country Dance and Song Society of America, NY, Second Revised edition, 1976. See also James J. Fuld and Mary Wallace Davidson, 18th Century American Secular Music Manuscripts: An Inventory, (Music Library Association, Philadelphia, PA, 1980) providing a census of manuscripts documenting the popularity of printed editions of American printed music for manuscripts started before 1801. |

| ↑21 | Ibid., p. 24. |

| ↑22 | Ralph Page, Heritage Dances of Early America, Lloyd Shaw Foundation, Colorado Springs, CO, printed by Century One press, Colorado Springs, Co, 1976. |

| ↑23 | Ibid., p. 18. |

| ↑24 | Ibid., p. 9. |

| ↑25 | Keller, Sweet, p. 11. |

| ↑26 | Page, p. 18. |

| ↑27 | Keller, Sweet, p. 24. |

| ↑28 | Fort Clatsop National Memorial, Astoria, OR. The author gratefully acknowledges the helpfulness of Superintendent Franklin Walker, Chief Ranger Curtis Johnson and Jane Warner, Visitor Services, in identifying data and references located at the Memorial, and making such resources available for the purposes of this paper. |

| ↑29 | Plato, Laws, Book II [653]. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.