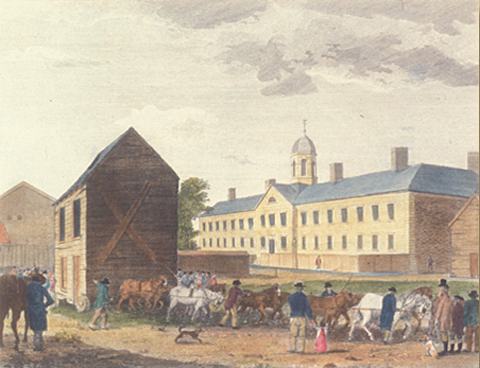

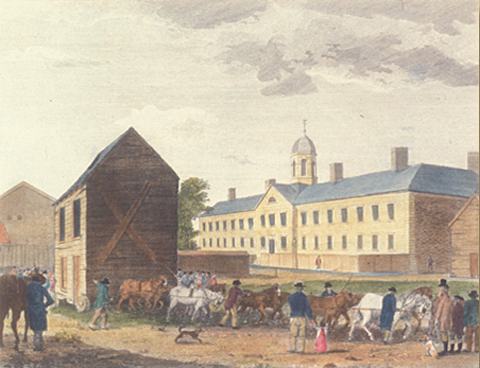

The paintings of William Birch preserve a period of epic expansion as Philadelphia became the scientific center of the young nation.

“Arch Street Ferry”

William Birch

Courtesy Independence National Historical Park, Karie Diethorn, Chief Curator, and with the kind assistance of library technician Andrea Ashby Leraris.[1]The prints in the INHP collection, which originated in various portfolio sets that preceded Birch’s book, The City of Philadelphia, in the State of Pennsylvania North America, as it appeared in … Continue reading

“The ground on which it stands,” wrote Birch in the preface to his collection of hand-colored engravings, The City of Philadelphia, . . . as it appeared in the Year 1800, “was less than a century ago, in a state of wild nature.” Situated about 100 miles up the Delaware River from the Atlantic Ocean, it had, he wrote, “in this short time, been raised, as it were, by magic power, to the eminence of an opulent city, famous for its trade and commerce, crouded in its port, with vessels of its own producing, and visited by others from all parts of the world.”

The Arch Street Ferry was one of the links between the thriving metropolitan area and the farms across the river in New Jersey.

William Russell Birch, a distinguished English artist known especially for his enamels of brilliant color and his miniature landscape engravings, was living at the time at his country house “Springland” north of Philadephia. A first edition copy of his famous views of Philadelphia, uniquely documenting an early American city, was then on display in the office of subscriber Thomas Jefferson, as it would be throughout his presidency. Although Birch found it easy to come by wealthy patrons, it was his interest to display not only the architecture of the young city but also the life of its inhabitants, whatever their occupations and status. There were always people in his scenes—often throngs of people. Their presence was not considered an obstruction to the view. The City of Philadelphia in the State of Pennsylvania as it Appeared in 1800 depicts not only the grand churches of the city but also a blacksmith’s shop being pulled to a new station in life as the first incarnation of Mother Bethel Church.

The buildings Birch portrayed have in turn tended to be those that have been preserved, restored or reconstructed, for which we are fortunate in the sense that the structures resurrect that particular brief period when an epic expansion began its exploratory trickle. The vigor of the expansion came close to ignoring and destroying some of the buildings we now honor by preserving. It certainly destroyed the rural countryside that once began at Ninth Street, to say nothing of the world of native peoples of the region and beyond. Birch’s scenes of Philadelphia displayed the strong foothold of the Europeanizatized that had begun at the eastern seaboard and was about to engulf all other societies. For the people along the Missouri who examined Jefferson’s portrait on an Indian peace medal, perhaps some glimpses from Jefferson’s copy of Birch’s plates would have made even clearer the solemn implications of the arrival of Lewis and Clark.

Featured Works

Lewis’s visit to Philadelphia in 1803 came at a time of diminished status for the State House. The national government had moved to Washington. Old City Hall was no longer occupied by the Supreme Court of the United States and Congress Hall was without Congress.

Rafinesque took a scientific interest in the plants and animals mentioned by Lewis and Clark. In addition to the six species of conifers, he also established the scientific name for the prairie dog, the white-footed mouse and the mule deer.

To understand the Lewis and Clark Expedition, one must understand this complex American leader.

Like the European charity hospitals, and unlike the Alms House a block away at 10th and Spruce, free medical care was to be provided for the poor, though paying patients were also welcomed. Not admitted were victims of contagious disease and “incurables” except “lunaticks.”

When Meriwether Lewis traveled to Philadelphia in 1802, his guide to the city was Mahlon Dickerson who gave him a survey of people and places well beyond the privilege or opportunity of most Philadelphians of the time.

Port and Shipyard

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Kensington was one of the two shipbuilding areas at Philadelphia. The other was at Humphrey’s Shipyard. The tree may have been the one beneath which William Penn consummated his peace treaty with the Lenni Lenape Indians.

Although it would be many years before the entire city had access to pure water, the completion of the Water Works in 1800 helped to reduce the threat of epidemics and provided a foundation for continued urban growth.

The irony inherent in the juxtaposition of the A.M.E. Church’s prime sanctuary as a symbol of fellowship and hope, with the Walnut Street Gaol (jail) as a place of isolation and despair, would not have been lost on any black person or white abolitionist.

The New Market

by Charles F. Reed

In 1845 the busy activity of the markets on High Street was matched by a new market on a slight elevation above Dock Creek, between Walnut and South Streets. The neighborhood was called Society Hill, from the Society of Traders that once had an office there.

Lewis may have viewed this bank as a symbol of a victory of Hamilton over Jefferson in the first clash of their respective interpretations of the Constitution.

Christ Church

by Charles F. Reed

One of Bishop White’s parishioners at Christ Church was George Washington. The burial ground contains Benjamin Franklin’s grave and those of seven other signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Notes

| ↑1 | The prints in the INHP collection, which originated in various portfolio sets that preceded Birch’s book, The City of Philadelphia, in the State of Pennsylvania North America, as it appeared in the Year 1800, measure approximately 18 by 14½ inches. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.