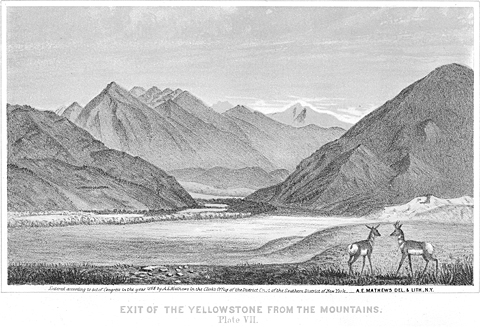

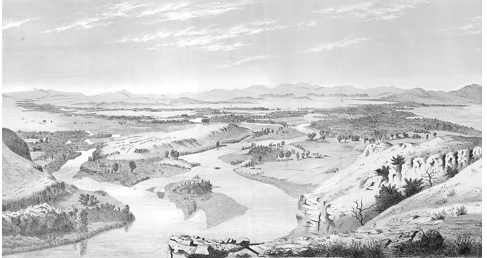

Lithograph from Pencil Sketches of Montana

by Alfred E. Mathews (1831-1874)

Published by the author in New York, in 1868. Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula.

Alfred Edward Mathews (1831-1874) emigrated to the U.S. from England to become an itinerant bookseller and artist. After serving in the Civil War he headed west, producing some of the earliest views of Texas (1861), Colorado (1866 and 1870), and Gems of Rocky Mountain Scenery: Containing Views Along and Near the Union Pacific Railroad (1869).

The technology basic to the science and art of photography evolved during the 18th and early nineteenth centuries. In 1816 a French scientist combined the camera obscura with photosensitive paper, and after ten more years of experimentation finally produced a permanent image. In 1837, Louis Daguerre successfully demonstrated his invention, by which a copper sheet coated with silver iodide was “exposed,” and then “developed” with warm mercury. The Daguerreotype was displaced in 1851 by the new and cheaper wet plate collodion process, which permitted unlimited reproductions, and which prevailed until George Eastman perfected a dry-plate process in 1879.

In his introduction to Pencil Sketches of Montana, Mathews expressed a conservative view on the aesthetics of outdoor photography:

The author has frequently been asked why he did not take a Photographic Instrument along, in order to photograph Mountain scenery; for it is generally supposed that a photograph of Mountain scenery is always perfectly accurate. This, however, is far from being the case. In taking a picture, the lens of an instrument must be adjusted to focus on a certain object or objects; and all others more distant, or nearer, will be more or less indistinct. Another disadvantage of an instrument is that objects near at hand are magnified, while those farther off are reduced in size. So apparent is this defect in large photographs of persons that a small picture is now first taken, and afterwards copied and enlarged. Shadows, too, are apt to be deepened and lights intensified. A good artist can, with ordinary care, produce a more accurate and pleasing picture with the pencil or brush.

Fundamentally, Mathews’ objection is still valid. The human eye, linked to the brain, is of course subjective, and thus selective; the camera lens, reacting only to light within the range of its own inanimate eye, is objective and comprehensive. However, during the twentieth century the medium became so integral a part of everyday life, worldwide, that its optical illusions are now tacitly accepted as realities.

Featured Works

Late in the day on 19 July 1805, Lewis and his party entered a canyon between “the most remarkable clifts that we have yet seen.” They seemed to rise “from the waters edge on either side perpendicularly to the hight of 1200 feet.”

The Bears Tooth was an important landmark on the the ancient Indian road that has come to be known as the Old North Trail. It was included on Nicholas King’s 1804 map, and the captains expected to find it.

As he started over the mountains at today’s Bozeman they observed several Indian and buffalo roads heading northeast across the mountains. Clark reported, “the indian woman who has been of great Service to me as a pilot through this Country recommends a gap.”

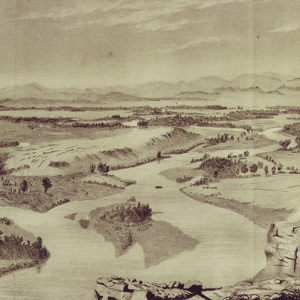

July 25, 1805

End of the Missouri

Early in the day, Clark reaches the headwaters of the Missouri. Lewis is behind with the dugouts. He describes the speed of pronghorns, and Clark explores what they would later name the Jefferson River.

After the expedition, the Three Forks area would see the death of Potts and Drouillard, the start of Colter’s famous run, and an emerging frontier lifestyle in Gallatin City, later to be known as Three Forks, Montana.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.