Side Stepping Orders

Dearborn gave the departing Lewis an order dated 2 July 1803, that seemed to limit his permanent “payload” party to the now accepted total number of 15 men: Lewis himself, another officer, 12 Army enlisted men and a hired interpreter. These soldiers also were to be obtained at Kaskaskia and other Illinois Army posts, or newly recruited into the Army from “suitable Men” encountered by Lewis along the way. “The whole number of non-commissioned officers and privates should not exceed twelve,” said Dearborn, setting a ceiling that would seem to apply to all the enlisted explorers, whether old soldiers or new recruits.

Yet here’s the way Lewis interpreted his authority in his June 19 letter inviting Clark in Louisville to join the expedition as co-captain:

I am instructed to select from any corps in the army a number of noncommissioned officers and privates not exceeding 12, who may be disposed voluntarily to enter into this service; and am also authorized to engage any other men not soldiers that I may think usefull in promoting the objects or success of this expedition. (emphasis added)[2]Thwaites, Reuben G., ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. (Antiquarian Press edition, N.Y., 1959), 7:227.

From this it would appear that Lewis decided the 12-man ceiling applied just to soldiers already serving, and that he could bring aboard as many additional civilians as he wanted. Lewis planned on his way down the Ohio to “engage some good hunters, stout, healthy, unmarried men, accustomed to the woods . . .” He suggested that Clark start a similar talent search around Louisville. The 12 soldiers would be picked up later, in Illinois.

Colter and Shannon Jump On

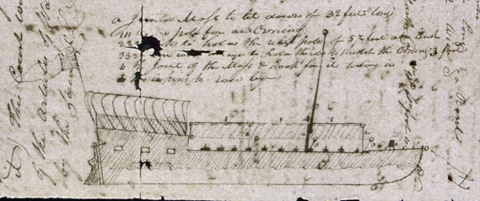

Clark’s Sketch

To see labels, point to the image.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

This military barge was designed by Lewis, built at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and floated down the Ohio River to the Expedition’s first (1803–1804) winter camp across the Mississippi from the mouth of the Missouri. The following spring it was taken to the Knife River Villages, 1600 miles up the Missouri and sent back down river the following spring.

Lewis left Washington for Pittsburgh on 5 July 1803, just having learned that the Louisiana treaty actually had been signed in Paris. His purchased cargo arrived in Pittsburgh on time, as did the temporary boat crew of seven Army recruits (one deserted), but tardy completion of the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) delayed his departure until August 31. Lewis headed down the Ohio with his seven soldiers, a river pilot and “three young men on trial” who wanted to go exploring. Several historians think one of them was George Shannon, who became the permanent party‘s youngest member.[3]Appleman, Roy E., Lewis and Clark: Historic Places Associated with Their Transcontinental Expedition. (National Park Service, Washington, 1975), 49; Dillon, Richard, Meriwether Lewis: A Biography. … Continue reading

John Colter jumped aboard the big boat as a permanent party volunteer at Maysville, Kentucky, according to Colter family tradition.[4]Appleman, 51. Thus, when Lewis arrived at Cincinnati on 28 September 1803, he wrote ahead to Clark that he now had just two young men on trial—presumably Shannon and Colter—who Lewis thought would “answer tolerably well.”

“Young men who joined at Clarksville”

The barge arrived at the Falls of the Ohio on 14 October 1803, and pulled into Clarksville, Indiana, across the river from Louisville, the next day. Clark was waiting with seven woodsmen he had picked for the expedition. in an interview with Nicholas Biddle seven years later, Clark referred to this group—plus Shannon and Colter—as a distinct cluster within the eventual permanent party, calling them the “young men who joined at Clarksville.”[5]Jackson, 2:534. When writing his 1814 narrative of the Expedition, Biddle used the expression “nine young men from Kentucky“—the label that has stuck to them ever since.

Clark also greeted Lewis by saying he would take a slave, York, to be his wilderness valet for the whole trip.

The leaders started laying their plans in detail. If Lewis ever thought of roaming the West with a split party of soldiers and civilian auxiliary hunters, the idea died right there: discipline would be impossible to maintain. Except for the authorized interpreter and York, everyone would have to be in the Army, equally subject to military orders. The Kentucky Nine were enlisted into the service on the spot . . .[6]Dates of enlistment for soldiers of the entire party are shown in Thwaites, 7:360. For the Kentucky Nine, enlistment was completed by 20 October 1803, six days before the Expedition left Louisville. But that, in turn, almost filled the Expedition’s authorized strength under Dearborn’s 12-soldier quota. Judging by their later actions, it must have been in Louisville that Lewis and Clark decided to keep adding more men, the quota and brother George’s advice notwithstanding. A locally written newspaper story attempting to describe the Expedition said “about 60 men will compose the party.”[7]Printed with a Louisville dateline in Philadelphia. Aurora, 17 November 1803, 2. While exaggerated, that was an indication the captains were already thinking big.

Fort Massac Additions

The barge left Louisville on 26 October 1803 and on 11 November 1803 came to its next stop, Fort Massac, on the Illinois side of the Ohio River. The post was garrisoned by Captain Daniel Bissell’s company of infantry, on which Lewis was authorized to draw volunteers. He came at a time of hectic turmoil for the American frontier Army, then preparing to send occupation troops westward into newly acquired Louisiana. The temporary boat crew from Pittsburgh, which dropped off here, was part of that movement. As far as is known, Lewis obtained only two privates from the Massac garrison. Worse, six to eight soldiers supposedly sent from South West Point weren’t waiting for him at Massac, as expected. To find them he dispatched George Drouillard, a locally renowned woodsman hired at Massac as the Expedition’s civilian interpreter.

At the mouth of the Ohio, Lewis and Clark turned northward into the Mississippi. Now the soldiers got their first taste of trying to make the big boat go upstream, which may have nailed down the captains’ conviction that a small crew wouldn’t do. On 28 November 1803, they pulled into the big Army post at Kaskaskia, on the Illinois shore. It was home to Captain Russell Bissell’s infantry company, plus an artillery company commanded by Captain Amos Stoddard, who was waiting to occupy St. Louis when the old owners moved out. Lewis wrote Jefferson that at Kaskaskia “I made a selection of a sufficient number of men from the troops of that place to complete my party.”[8]Jackson, 1:145. He didn’t say how many, but it probably was something more than a dozen, including the small boat escort group plus men for the permanent party.

Notes

| ↑1 | Arlen J. Large, “‘Additions to the Party’: How an Expedition Grew and Grew,” We Proceeded On, February 1990, Volume 16, No. 1, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. Editorial additions include page titles, side headings, and graphics to assist the web-based reader. The original full-length article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol16no1.pdf#page=4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Thwaites, Reuben G., ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. (Antiquarian Press edition, N.Y., 1959), 7:227. |

| ↑3 | Appleman, Roy E., Lewis and Clark: Historic Places Associated with Their Transcontinental Expedition. (National Park Service, Washington, 1975), 49; Dillon, Richard, Meriwether Lewis: A Biography. (Coward-McCann, N.Y., 1965), 58. |

| ↑4 | Appleman, 51. |

| ↑5 | Jackson, 2:534. |

| ↑6 | Dates of enlistment for soldiers of the entire party are shown in Thwaites, 7:360. For the Kentucky Nine, enlistment was completed by 20 October 1803, six days before the Expedition left Louisville. |

| ↑7 | Printed with a Louisville dateline in Philadelphia. Aurora, 17 November 1803, 2. |

| ↑8 | Jackson, 1:145. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.