Editor’s Note: Archaeological investigations by the author and his students between 2017 and 2019 revealed the location of the American Fort Kaskaskia one hundred yards north of the older French fort. Below are extracts—mainly the introduction and sidebars—from “Bound to the Western Waters: Searching for Lewis and Clark at Fort Kaskaskia, Illinois” which document their work and findings. The complete We Proceeded On article is available at our sister site: lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol47no1.pdf#page=25.[1]Extracts from Mark J. Wagner, “Bound to the Western Waters: Searching for Lewis and Clark at Fort Kaskaskia, Illinois,” We Proceeded On, 47:1, 25–29. Dr. Mark J. Wagner is the Director … Continue reading

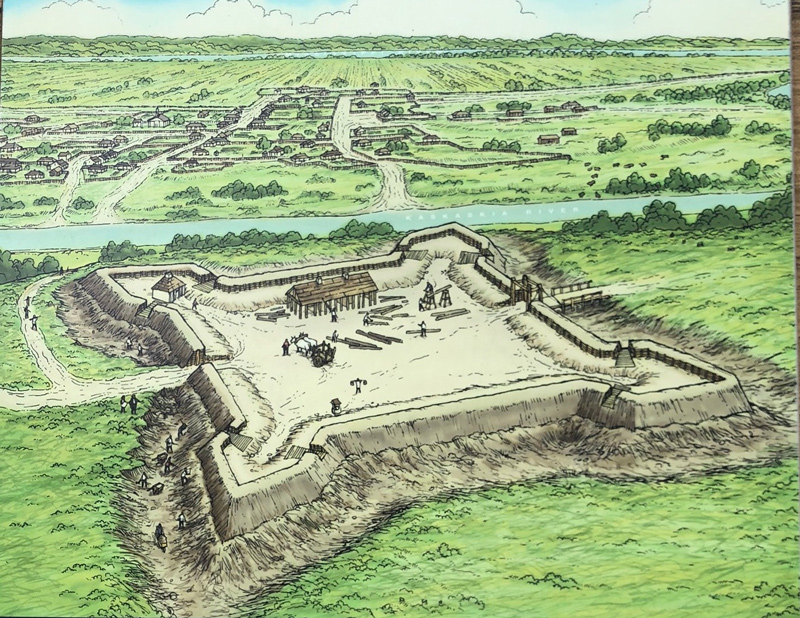

Fort Kaskaskia View

© 5 March 2012 by Goodpairofshoes. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FortKaskaskiaView.jpg accessed on 21 April 2022.

Both the American and French forts provided a strategic view of the important village of Kaskaskia across what was then the Kaskaskia River. The Mississippi channel now flows in the channel directly below the bluff.

The small American military outpost of Fort Kaskaskia (1803–1807), Illinois, played a pivotal role in the early days of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Fort Kaskaskia was one of a series of forts constructed by the U.S. Army in 1803 under orders from Secretary of War Henry Dearborn to protect the frontier. It was there on 29 November 1803, that Lewis and Clark stopped to recruit eleven soldiers (Table 1)[2]Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), 122–123.. Lewis and Clark lingered at Fort Kaskaskia for about a week, conducting business or visiting influential citizens such as fur trader and merchant Pierre Menard in the nearby town of Kaskaskia. With the departure of Lewis on 3 December 1803, followed by Clark on 7 December 1803, the fort slipped away into obscurity.

Table 1. Lewis and Clark Expedition Men Recruited at Fort Kaskaskia

- Captain Amos Stoddard‘s Artillery[3]Captain Amos Stoddard commanded an artillery company (approximately forty men) at Fort Kaskaskia in 1803. He and part of his company represented the United States in St. Louis in March 1804 when … Continue reading

- Captain Russell Bissell’s 1st Infantry[4]Captain Russell Bissell was a former Revolutionary War soldier who commanded a company (about eighty men) of the 2nd Infantry Regiment (approximately 800 men) in 1802. When President Thomas Jefferson … Continue reading

- Civilian Recruit

The French Fort Kaskaskia

The French Redoubt

From an interpretive sign at Fort Kaskaskia State Historic Site. Source: “Fort Kaskaskia,” Mythic Mississippi Project, https://mythicmississippi.illinois.edu/french-towns/fort-kaskaskia/, accessed 20 April 2022.

The old Kaskaskia village was located west of the Kaskaskia River and east of the Mississippi. The French fort was never completed.

Illinois was a key part of the French empire in the mid-continent during the eighteenth century, helping to protect the Mississippi River which linked French Louisiana and Canada. The French began construction of Fort Kaskaskia in 1759 during the Seven Years War (1756–1763) to protect the nearby town of Kaskaskia but abandoned it before it was completed. British soldiers sent to occupy Illinois in 1765 reported that the unfinished Fort Kaskaskia consisted of a rectangular earthworks faced with horizontal logs. Only two buildings—a barracks and bake house—had been completed within the fort interior. The British Lieutenant Phillip Pittman, who completed the first detailed map of the fort in 1766, described it as unfinished with “most of the planks and timbers rotten . . . the ditch, parapet, and ramparts entirely overgrown with bushes.” The people of Kaskaskia supposedly set fire to the abandoned fort in 1766 to stop the British from occupying it. Their plan, if that is what it was, failed as the British decided instead to construct a fort in the heart of Kaskaskia named Fort Gage. They continued to occupy Fort Gage until 1779 when it and the town of Kaskaskia were captured by Virginia troops under the command of George Rogers Clark during the American Revolution. The French Fort Kaskaskia was repaired and later used by an American adventurer named John Dodge to control the town of Kaskaskia for several years before he fled to Missouri in the 1780s.

The American Fort Kaskaskia

2nd Infantry Regiment Button

From the author.

Early 1800s U.S. Army 2nd Infantry Regiment pewter button found at American Fort Kaskaskia (Site 11R612) in 2017.

Artillery Button Model 1802–1808

Artifact on display at Fort Walla Walla, Washington. Photo © Kristopher K. Townsend 30 September 2015.[5]For more on this artillerist’s button, see A Manual for Interpreting Lewis and Clark (Great Falls: Lewis & Clark Honor Guard, 2003), 51 and Tice, W. K. Uniform Buttons of the United States … Continue reading

The 1803 construction of the American Fort Kaskaskia was tied to the Louisiana Purchase of that same year. Secretary of War Henry Dearborn instructed two U.S. Army officers—Major Amos Stoddard and Captain Russell Bissell—to identify a location for a new fort that would help establish an American military presence in the St. Louis area. The two officers suggested a location northeast of St. Louis within Illinois, but Dearborn told them instead to lease 150 acres southeast of St. Louis on the bluff top overlooking Kaskaskia. Bissell’s company of the 2nd (later to become the 1st) Infantry Regiment was already stationed there and living in log huts, which may have factored into Dearborn’s decision.

Kaskaskia also was the center of all political and economic activity in Illinois at that time with an estimated population of 7,000. In September 1803 the Army leased 150 acres from General John Edgar, a prominent Kaskaskia businessman, for three years for the construction of the fort. The fort plans have not been found, but it probably consisted of barracks and other buildings enclosed within walls of wooden pickets with blockhouses at the corners similar to other American frontier forts of the period. When Lewis and Clark visited in November 1803 the fort most likely was still under construction. Captain Bissell commanded a company of the 1st (formerly the 2nd) Infantry Regiment while Major Stoddard commanded an artillery unit of about forty men. It is doubtful that all of these men were present at the fort at any one time. A requisition to Captain Amos Stoddard for 175 pounds of gunpowder from Fort Kaskaskia signed by Meriwether Lewis still exists in the Amos Stoddard Manuscript Collection in the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis.[6]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1753–1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963), 1:142. Robert Stoddard, a descendant of Amos Stoddard, has recently argued that Fort Kaskaskia was intentionally constructed to pre-position men and supplies for the Lewis and Clark Expedition. This argument has some merit in that the Army held only a three-year lease on the fort site, which appears to have been abandoned shortly after the return of the expedition in 1806. Over the years the location of this small fort was completely forgotten as it became confused in memory with the earlier French fort of the same name.

An English Fort?

Kings 8th Regiment of Foot Button

From the author.

Kings 8th Regiment of Foot Button (replica)

From the author.

“Kings 8th Regiment of Foot” Revolutionary War British uniform button recovered at French Fort Kaskaskia and modern replica of this same button.

Early Illinois historians argued back and forth for decades about whether the British ever reoccupied the old French Fort Kaskaskia in the 1760s. They eventually concluded that the British instead built an entirely new fort called Fort Gage in the heart of Kaskaskia. So the discovery of a button from a Revolutionary War British unit—the King’s Own 8th Regiment of Foot—from a fort that British soldiers are believed never to have occupied raises the question of “how did it get here?” The answer may lie in Colonel George Rogers Clark’s attack on the British fort at Vincennes, Indiana, in 1779. George Rogers Clark had captured both Vincennes and Kaskaskia in the summer of 1778. While at Fort Kaskaskia, he learned that the British governor, Colonel Henry Hamilton, had come down from Detroit with a force of thirty-seven soldiers of the King’s Own 8th Regiment of Foot, militia, and Indians and retaken Vincennes. George Rogers Clark immediately led an overland march in the dead of winter under terrible conditions across southern Illinois to re-capture Vincennes in February 1779. He subsequently sent Hamilton and the British soldiers he captured as prisoners east to Virginia, raising the question once again of “how did one of their uniform buttons travel in the opposite direction to Fort Kaskaskia?” The most likely answer is that one of George Rogers Clark’s men in need of warm clothing in the dead of winter stripped a British prisoner of his uniform coat and wore it back home to Kaskaskia.

After the Expedition

Patrick Gass’ biographer claimed that he became the assistant commissary or civilian supply officer for “the outpost of Kaskaskia” after the return of the expedition in 1806.[7]J. G. Jacob, ed., The Life and Times of Patrick Gass (Wellsburg, Va.: Jacob & Smith, Publishers and Printers, 1859), 141. Census records indicate that Gass indeed was present in the nearby town of Kaskaskia as late as 1810, so he may have been acting as a local agent for a man from Kentucky who held the primary contract to supply the post.

The remains of the Lewis and Clark-era Fort Kaskaskia (Illinois Archaeological Survey [IAS] site 11R612) as well as that of an earlier French fort of the same name are today contained within the Fort Kaskaskia State Historic Site in southwestern Illinois. This park was established in the early 1900s to protect the 1750s French Fort Kaskaskia, which now consists of a series of grass-covered earthworks enclosed by a moat, its log walls long vanished. Because both the French and American forts had the same name, researchers had long assumed that they were one and the same, with the American Fort Kaskaskia constructed on top of and through the earlier French fort.

For all intents and purposes, the fort appears to have been abandoned by the U.S. Army by at least 1807. Parts of it may have been reused as an Illinois militia outpost during the War of 1812, but after that nothing more is heard of it, its location and very existence quickly forgotten.

Notes

| ↑1 | Extracts from Mark J. Wagner, “Bound to the Western Waters: Searching for Lewis and Clark at Fort Kaskaskia, Illinois,” We Proceeded On, 47:1, 25–29. Dr. Mark J. Wagner is the Director of the Center for Archaeological Investigations and Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale where his research interests include the Native American rock art of Illinois as well as historical archaeology. He has been researching the Lewis and Clark Expedition since 2003 when he directed an archaeological project that relocated the site of Cantonment Wilkinson, a very large 1801-1802 U.S. Army base in southern Illinois at which several of the Lewis and Clark Expedition men, including Patrick Gass, served prior to the expedition. For more about the project and a link to an interview with Dr. Wagner, see “Fort Kaskaskia,” Mythic Mississippi Project, https://mythicmississippi.illinois.edu/french-towns/fort-kaskaskia/, accessed 20 April 2022. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), 122–123. |

| ↑3 | Captain Amos Stoddard commanded an artillery company (approximately forty men) at Fort Kaskaskia in 1803. He and part of his company represented the United States in St. Louis in March 1804 when Spain transferred Upper Louisiana including St. Louis to France, which in turn transferred it to the United States a day later. Stoddard later died from wounds received at the Battle of Fort Meigs in Ohio during the War of 1812 in May 1813. Robert A. Stoddard, ed., The Autobiography Manuscript of Major Amos Stoddard (San Diego: Robert Stoddard Publishing, 2016), 48–51. |

| ↑4 | Captain Russell Bissell was a former Revolutionary War soldier who commanded a company (about eighty men) of the 2nd Infantry Regiment (approximately 800 men) in 1802. When President Thomas Jefferson reduced the size of the Army that same year, many of the 2nd Infantry companies including Bissell’s were transferred to the 1st Infantry Regiment. This accounts for the presence of both 1st and 2nd Infantry buttons at Fort Kaskaskia as many of Bissell’s men apparently were wearing a combination of buttons from their old and new regiments on their uniforms. Bissell was promoted to Major in the 1st Infantry Regiment in 1807, but died of illness almost immediately afterwards. He is buried in Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. |

| ↑5 | For more on this artillerist’s button, see A Manual for Interpreting Lewis and Clark (Great Falls: Lewis & Clark Honor Guard, 2003), 51 and Tice, W. K. Uniform Buttons of the United States 1776–1865 (Gettysburgh, Thomas Publications, 1997). |

| ↑6 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1753–1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963), 1:142. |

| ↑7 | J. G. Jacob, ed., The Life and Times of Patrick Gass (Wellsburg, Va.: Jacob & Smith, Publishers and Printers, 1859), 141. |