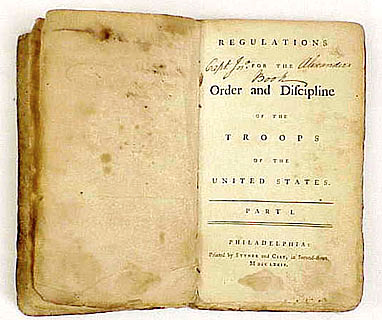

Regulations for the Order and Discipline of Troops of the United States. Part I

The John F. Reed Collection, Valley Forge National Historical Park, VAFO 3977

1779, 1st Edition. Philadelphia. Published by Styner and Cist (on order of Congress)

Paper, leather. W 11.9, H 19.1, T 1.9 cm

The handwritten inscription on the front cover says “July the 28th. 1779 Capt. John Alexander, 7th Pennsylvania Regiment.”

In February 1778 Frederick William Augustus, Baron von Steuben (or de Stuben), bearing a letter of recommendation from Benjamin Franklin, offered his services to General George Washington at the Continental Army’s Valley Forge encampment.

Having gained his military experience in the Prussian army during the Seven Years’ War (1756-63), Steuben quickly gained the respect and confidence not only of Washington but also of the rag-tag, dispirited American army. After personally training an elite drill company to demonstrate his principles of discipline, order, and method throughout the revolutionary forces, he began writing a manual titled Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. First published in 1778 and reprinted in 1794, it remained the U.S. army’s official handbook until 1812.[1]Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the troops of the United States . . . , by Baron de Stuben [sic], Late Major General and Inspector General of the Army of the United States. (1794; … Continue reading

Steuben’s book was much more than a “blue book” of military regulations and procedures. It concluded with guides to character, pride and conduct for men of every rank, from regimental commanders and their subordinates, to non-commissioned officers and privates.

It was in his instructions for each of the twelve ranks of officers soldiers in a battalion that the character of Steuben’s style of command was best illustrated. He emphasized the obligations of officers to the government and the people, the importance of orderliness and cleanliness, and the maintenance of a firm but even-handed chain of command. In several significant ways, the background in Steuben’s Regulations Lewis and Clark had gained under General Anthony Wayne provided some of the keys to the expedition’s success.

Directions for Privates

The recruit having received his necessaries, should in the first place learn to dress himself with a soldier-like air; to place his effects properly in his knapsack, so as to carry them with ease and convenience; how to salute his officers when he meets them; to clean his arms, wash his linen and cook his provisions. He should early accustom himself to dress in the night; and for that purpose always have his effects in his knapsack, and that placed where he can put his hand on it in a moment, that in case of alarm he may repair with the greatest alertness to the parade.

When learning to march, he must take the greatest pains to acquire a firm step and a proper balance, practicing himself at all his leisure hours. He must accustom himself to the greatest steadiness under arms, to pay attention to the commands of his officers, and exercise himself continually with his firelock, in order to acquire vivacity in his motion. He must acquaint himself with the usual beats and signals of the drum, and instantly obey them.

When in the ranks, he must always learn the names of his right and left hand men and file-leader, that he may be able to find his place readily in case of separation. He must cover his file-leader and dress well in his rank [align himself with the third man in front of him], which he may be assured of doing when he can just perceive the breast of the third man from him. Having joined his company, he must no longer consider himself as a recruit, but as a soldier; and whenever he is ordered under arms, must appear well dressed, with his arms and accoutrements clean and in good order, and his knapsack, blanket, &c. ready to throw on his back in case he should be ordered to take them.

When warned for guard, he must appear as neat as possible, carry all his effects with him, and even when on sentry must have them at his back. He must receive the orders from the sentry he relieves; and when placed before the guard-house, he must inform the corporal of all that approach, and suffer no one to enter until examined; if he is posted at a distance from the guard, he will march there in order, have the orders well explained to him by the corporal, learn which is the nearest post between him and the guard, in case he should be obliged to retire, or have any thing to communicate, and what he is to do in case of alarm; or if in a town, in case of fire and any disturbance. He will never go more than twenty paces from his post; and if in a retired placed, or in the night, suffer no one to approach within ten paces of him.

A sentinel must never rest upon his arms, but keep walking on his post. He must never suffer himself to be relieved but by his corporal; challenge briskly in the night, and stop those who have not the countersign; and if any will not answer to the third challenge, or having been stopped should attempt to escape, he may fire on them.

. . . When arrived at camp or quarters, he must clean his arms, prepare his bed, and go for necessaries, taking nothing without leave, nor committing any kind of excess.

He must always have a stopper for the muzzle of his gun in case of rain, and when on a march; at which times he will unfix his bayonet.

Instructions for Captains (partial)

A Captain cannot be too careful of the company the State has committed to his charge. He must pay the greatest attention to the health of his men, their discipline, arms, accoutrements, ammunition, clothes and necessaries.

His object should be, to gain the love of his men, by treating them with every possible kindness and humanity, enquiring into their complaints, and when well founded, seeing them redressed. He should know every man of his company by name and character. He should often visit those who are sick, speak tenderly to them, see that the public provision, whether of medicine or diet, is duly administered, and procure them besides such comforts and conveniencies as are in his power. The attachment that arises from this kind of attention to the sick and wounded, is almost inconceivable; it will moreover be the means of preserving the lives of many valuable men. . . .

He must keep a strict eye over the conduct of the non-commissioned officers; oblige them to do their duty with the greatest exactness; and use every possible means to keep up a proper subordination between them and the soldiers: For which reason he must never rudely reprimand them in presence of the men, but at all times treat them with proper respect.[2]Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. to which is added, An Appendix, containing, the United States Militia Act, Passed in Congress, May, 1792, by Baron de … Continue reading

Similar instructions directed toward commissioned junior officers, or subalterns—lieutenants and ensigns—followed by instructions for the sergeant-major, quartermaster sergeant, and first sergeant of a company. Next came instructions for sergeants and corporals, who commanded platoons and squads.

Instructions for Sergeants

It being on the non-commissioned officers that the discipline and order of a company in a great measure depend, they cannot be too circumspect in their behaviour towards the men, by treating them with mildness, and at the same time obliging every one to do his duty. By avoiding too great familiarity with the men, they will not only gain their love and confidence, but be treated with a proper respect; whereas by a contrary conduct they forfeit all regard, and their authority becomes despised.

Each serjeant and corporal will be in a particular manner answerable for the squad committed to his care. He must pay particular attention to their conduct in every respect; that they keep themselves and their arms always clean; that they have their effects always ready, and put where they can get them immediately, even in the dark, without confusion; and on every fine day he must oblige them to air their effects.

. . . In teaching the recruits, they must exercise all their patience, by no means abusing them, but treating them with mildness, and not expect too much precision in the first lessons, punishing those only who are willfully negligent.

They must suppress all quarrels and disputes in the company; and where other means fail, must use their authority, confining the offender.[3]Ibid., 144-47.

Adapting Steuben’s Regulations

On 31 March 1804, the captains selected “the Detachment destined for the Expedition through the interior of the Continent of North America,” including the men who were to take the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) back to St. Louis. On the next day they formalized the process in a detailed set of Detachment Orders. They appointed three sergeants—Charles Floyd, John Ordway, and Nathaniel Pryor—”with equal Power (unless when otherwise specially ordered).” To insure order among the party, they continued, “as well as to promote a regular Police in Camp, The Commanding officers, have thought to devide the detachment into three Squads, and to place a Sergeant in Command of each, who are held imediately responsible to the Commanding officers, for the regular and orderly deportment of the individuals Composeing their respective Squads.” With apparently some participation from the enlisted men, they assigned eight to each squad, then ordered the sergeants to divide their respective squads into two messes, or eating units, and distributed “Camp Kittles, and other Public utensels for Cooking.” All in all, these Detachment Orders duly reflected the spirit of the procedures Baron von Steuben had outlined.

Two of the three appointed sergeants—Charles Floyd and Nathaniel Pryor—had no background in the Army before they enlisted in the detachment that was to become the Corps of Discovery. This suggests that both captains relied on their own abilities to recognize positive leadership qualities in men who may not themselves have claimed them. There are no indications in the journals that Lewis and Clark systematically indoctrinated the green sergeants into the basic regulations as laid down by Steuben. Instead, marksmanship, which was of secondary importance to Steuben, was cultivated and encouraged, partly in order to sort out the best hunters. To expedite that process, Lewis declared in his orders of 20 February 1804, that riflemen would “in futur discharge only one round each per. day, . . . all at the same target and at the distance of fifty yards off hand.” He made the effort worth their attention by offering an extra gill of whiskey, plus exemption from guard duty, to each day’s best marksman.

Of the members of the permanent company who completed the round trip, thirteen volunteered from four different frontier garrisons, including the First Infantry Regiment and the artillery company at Kaskaskia, Indiana Territory; another company of the First Infantry Regiment at Fort Massac, also in Indiana Territory; and the Second Infantry Regiment at South West Point, Tennessee. It is uncertain whether McNeal, Goodrich, Frazer, Thompson or Werner were previously in the army or not. Privates Pierre Cruzatte and Labiche were civilians who were enlisted at St. Charles on the basis of their qualifications as boatmen experienced in navigating the Missouri River. It was a motley crew, indeed, and Lewis and Clark—especially Clark—knew from their experiences on the frontier in Ohio and Indiana which of Steuben’s instructions would work on this expedition, and which would not.

Most of Steuben’s instructions for the “private Soldier” were aimed toward making him an effective and reliable member of a well-coordinated frontline musket-and-bayonet battle force. They would have held no relevance to the needs of an exploratory team, who had to be capable of wrestling heavily loaded boats up or down challenging rivers, or coaxing cooperation from headstrong Indian horses. It is clear Lewis knew from his own experience that they would need “good hunters, stout, healthy . . . men, accustomed to the woods, and capable of bearing bodily fatigue in a pretty considerable degree,” and that Clark understood precisely what he meant.[4]Lewis to Clark, 19 June 1803. Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854; 2nd ed.; 2 vols. (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:58. Despite the disciplinary problems Clark had to cope with that winter, he recognized the qualities he valued in the members of the permanent party on the day of their departure from Wood River, but in candor crossed out his true assessment of them: “robust Young Backwoodsmen of Character helthy hardy young men, recommended.”

One of Steuben’s incidental directions to captains, “to prevent the soldier loading himself with unnecessary baggage,” and correspondingly to the “private Soldier” not to “charge himself with any unnecessary baggage,” came up during the expedition. On the day the party left the upper portage camp at the Great Falls of the Missouri in their heavily loaded dugout canoes, Lewis admitted the futility of bucking the universal tourist’s curse: “we find it extreemly difficult to keep the baggage of many of our men within reasonable bounds; they will be adding bulky articles of but little use or value to them.”

Notes

| ↑1 | Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the troops of the United States . . . , by Baron de Stuben [sic], Late Major General and Inspector General of the Army of the United States. (1794; Reprint, New York, Dover, 1985), 147-51. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. to which is added, An Appendix, containing, the United States Militia Act, Passed in Congress, May, 1792, by Baron de Stuben [sic]. Boston: Thomas and Andrews, 1794. Facsimile reprint (New York: Dover, 1985), 134-35. Steuben insisted a captain “must keep a book, in which must be entered the name and description of every non-commissioned officer and soldier in his company,” including “his trade or occupation; the place of his birth and usual residence; where, when, and for what term he inlisted.” Had one of the captains only done so, we would now be able to memorialize the contributions of all the men in the Corps on an equal basis. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., 144-47. |

| ↑4 | Lewis to Clark, 19 June 1803. Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854; 2nd ed.; 2 vols. (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:58. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.