“Lewis could write at great length about the taxonomy of plants and animals because the relatively advanced state of botany and zoology gave him the intellectual framework and vocabulary to do so. It was the nascent state of geology, not deficiencies in the captains’ dedication or attention, that precluded similar efforts in the science of rocks and minerals.”

The Fort Mandan shipment of specimens was registered in the so-called “Donation Book” that was compiled for the Lewis and Clark materials received in November 1805. The entries were sequentially numbered by John Vaughan of the APS in Philadelphia.

Paleontology

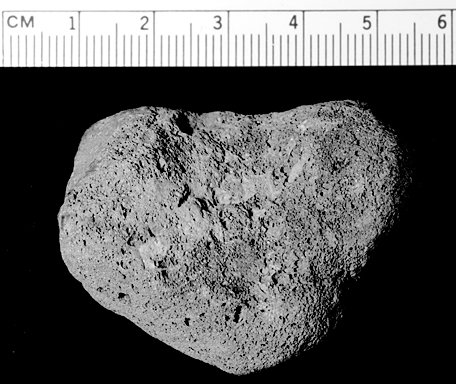

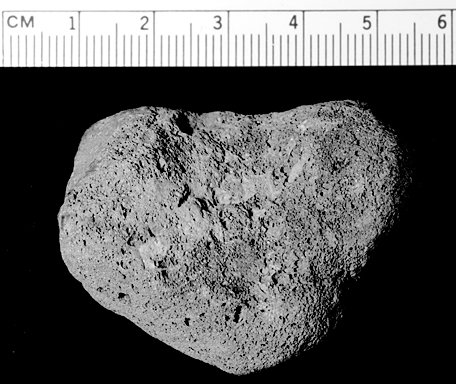

After leaving Pittsburgh, Lewis had his first opportunity to personally delve into the new science of paleontology—a trip to Big Bone Lick. Despite his efforts there, the only known fossil specimen to survive was found by Sgt. Patrick Gass and recorded by Lewis prior to shipment from Fort Mandan.

The Missouri River exposed rock formations that were geologically diverse, distinctly colored, rich in mineral content, and in some places, dramatically distinguished by steaming and smoking hot earth that beckoned to be investigated.

Searching for Lead

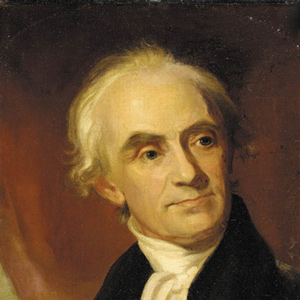

by John W. Jengo

In the afternoon of 4 June 1804, William Clark decided to investigate the purported occurrence of lead in the vicinity of a rather unique prominence he named “Mine Hill,” but which is known today as Sugar Loaf Rock. The search was unsuccessful, but Lewis’s previous inquiries while in St. Louis resulted in 11 specimens sent to Thomas Jefferson.

Missouri River Geology

The Missouri River exposed rock formations that were geologically diverse, distinctly colored, rich in mineral content, and in some places, dramatically distinguished by steaming and smoking hot earth that beckoned to be investigated.

Pumice Stone

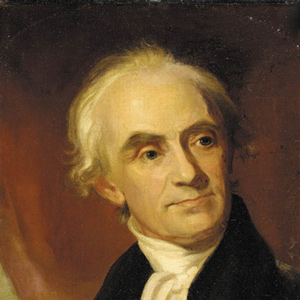

by Robert N. Bergantino

“The Pumies Stone which is found as low as the Illinois Country is formed by the banks or Stratums of Coal taking fire and burning the earth imedeately above it into either pumies Stone or Lavia. This Coal Country is principly above the Mandans.”

October 19, 1803

Clarksville Fossil beds

In Louisville, Gibson, Shields, and Shannon officially enlist as privates in the “corps of volunteers for North West Discovery”. The Clarksville fossil beds are described by contemporary travelers.

Among the “objects worthy of notice” President Jefferson instructed Meriwether Lewis to watch for en route were saltpetre deposits and salines. By “salines” Jefferson meant salt flats, salt marshes, salt pans, salt springs, and rock or “fossil” salt deposits.

Columbia River Geology

The route down the Snake and Columbia Rivers, amongst dark menacing rocks and through ferocious whitewater rapids, was perhaps the most thrilling, dramatic, and geologically fascinating.

The expedition camped amid very picturesque boulders of pink granite at Lolo Hot Springs, and crossed large masses of it on their way across Idaho.

Although not nearly as celebrated as their botanical and zoological work, Lewis and Clark collected a multitude of mineralogical specimens throughout the expedition.

The lignite in the Fort Union Formation ignites easily. Sometimes the materials adjacent to the burning coal beds become so hot that they actually froth and, when cooled, resemble the bubbly and cratered volcanic rock called pumice.

As a reference, Lewis purchased the second edition (1784) of Richard Kirwan’s Elements of Mineralogy. Although Lewis and Clark had the book at hand throughout the expedition, its usefulness as a field guide was limited.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.