Thomas Jefferson loved secrecy. In his dining room at the President’s House, a sort of Lazy Susan of circular shelves could be rotated right through the wall, so that servants isolated in the next room could pass dishes to the diners without overhearing any juicy government gossip. During the planning and preparation of the Western Expedition, Thomas Jefferson practiced selective levels of secrecy.

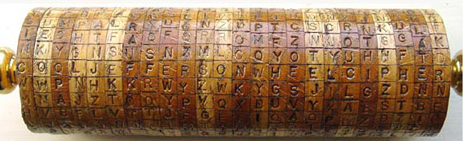

Jefferson’s Cipher Wheel

© Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc.

A 24-wheel reproduction of Jefferson’s 26-wheel cipher, otherwise built according to his instructions.

It was in character, then, for Jefferson to conceal selectively his plans for a government scouting trip overland to the Pacific Ocean. Because he needed public money for it, he had to take Congress into his confidence, but only under a stamp of “CONFIDENTIAL.” Even some close associates were given a false cover story about the explorers’ true destination. In sensitive matters the scouting party was to talk to headquarters in code (See Jefferson-Lewis Cryptology). All that stealth may look overly cautious, but it fit an era prone to intrigue. After all, the top U.S. Army general (James Wilkinson) was then in the pay of a foreign king, and giving secret advice on bow to stop the Lewis and Clark Expedition in its tracks.

Jefferson’s Confidential Request

On 18 January 1803, the Senate’s Executive Journal recorded the delivery of a confidential message from the President “by Mr. Lewis, his Secretary.” The 32 Senators were meeting in the first completed section of the Capitol, a boxy sandstone-walled unit just north of today’s center dome. Lewis took another copy to the 105 Representatives assembled in the “oven,” a temporary oval structure standing where the sandstone House wing would go up the following year. There, arrival of the President’s message caused the Speaker to clear the spectators’ galleries; after a ten-minute reading of the text, the public was re-admitted.[1]Washington National Intelligencer, 19 January 1803, 2.

Lewis’s role as courier was especially fitting, for this message was crucial to his next assignment of leading the proposed expedition to the Pacific. The message had two parts, the first dealing with government-run trading houses for Indians east of the Mississippi. Second, Jefferson said he wanted to send a small exploring party up “the whole line” of the Missouri River “even to the Western ocean.” In talks with the local Indians, the explorers would tout the advantages of dealing with a coming network of American traders. The President predicted this new transcontinental network would offer hot competition “to the trade of another nation, carried on in a high latitude … ” (He didn’t name that nation, but anyone could have shouted “Great Britain!”) The President added there would be a scientific bonus from gaining “geographical knowledge of our own continent,” and concluded:

“The appropriation of $2,500 ‘for the purpose of extending the external commerce of the U.S.,’ while understood and considered by the Executive as giving the legislative sanction, would cover the undertaking from notice, and prevent the obstructions which interested individuals might otherwise previously prepare in it’s way.”[2]Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Reuben Thwaites, ed. (New York: Antiquarian Press edition, 1959), 7:208-209.

Why?

Some historians have asked whether Jefferson fully leveled with Congress on his reasons for the expedition. But if it’s true he was mainly responding to Alexander Mackenzie‘s 1801 book urging expansion of Britain’s fur trade to the Pacific Northwest, then the American sortie to thwart Mackenzie’s plan was quite accurately explained to Congress: let’s take away their business. Who Jefferson didn’t fully level with were the diplomats of Britain, France and Spain. From them he sought passports for the American explorers, explaining in pseudo-confidence that he really wanted only a “literary,” or scientific, operation, but that the Constitution made him give it a commercial gloss to sneak it past Congress.

Since the President plainly told the diplomats his scouts would aim for the Pacific via the Missouri, who was all the secrecy directed at? Donald Jackson, the expedition’s respected chronicler, thought Jefferson “feared the intervention of his political enemies.”[3]Carlos Martinez de Yrujo to Pedro Cevallos, 31 January 1803 in Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois … Continue reading Yet Congress was the last national redoubt of his political enemies, harboring a loud minority of 50 Federalists, and Congress got the true story. Jefferson more likely wanted to hide his message’s anti-British strategy specifically from Edward Thornton, King George’s temporary envoy to America. Just then Jefferson was worried about a possible war over New Orleans with France, its new owner, in which case he would want Britain on his side.

Thornton apparently bought it. To their lordships in Whitehall he passed along unskeptically Jefferson’s story about a strictly literary venture. Thornton not only gave the expedition a passport (See February 28, 1803), but also is believed to have let Lewis copy a valuable map of the upper Missouri River, as drawn by British surveyor David Thompson.

The Bills

Congress, meanwhile, split the two topics of Jefferson’s 18 January message into separate legislative bills, and passed the Indian trading house measure routinely. The other bill granting $2,500 for the Pacific expedition temporarily sank from sight Lobbyists of that day didn’t have the luxury of televised floor proceedings, or a verbatim account in a thick Congressional Record available the following morning. Legislative developments had to be tracked in the major newspapers, which hired stenographers to sit in the galleries and take everything down word-for-word.

Under Senate rules, Presidential messages labeled “confidential” were to be “kept inviolably secret.” Rumors, of course, could always filter out, and one of them fooled the Spanish ambassador. On 31 January, he reported to his superiors that the expedition’s $2,500 appropriation was in trouble in the Senate, “and consequently it is very probable that the project will not proceed.”[4]Jackson, 1:15.

However, on 22 February 1803, the Senate passed the bill without even bothering with a roll-call vote—a sign of harmony—and sent it to the House. This closed-door action escaped notice by the Washington National Intelligencer, but at the end of its account of House proceedings for the same day, the newspaper printed this terse sentence: “The galleries were cleared to take up two bills of a confidential nature received from the Senate.”[5]National Intelligencer, 23 February 1803, 3. One was the expedition’s appropriation, which the House then passed. Having been approved by both houses in identical form on 22 February, the $2,500 appropriation “for the purpose extending the external commerce of the United States” was signed by the President on 28 February. The Intelligencer printed the bill’s inscrutably brief text, with no hint of a Pacific expedition, on 14 March. Today, incidentally, Congress no longer passes secret bills in secret, though it regularly hides money for the CIA within routing appropriations for other agencies.

Clark’s Secrecy

If the President had an arguable case for misleading Britain, there was one other tight secret justifiably guarded during the expedition’s planning stage. In his 19 June 1803, letter to Louisville, Kentucky, inviting William Clark to be co-leader, Lewis told Clark to keep mum about the whole plan, and then doubly swore him to secrecy about the government’s “very sanguine expectations” of soon buying all of Louisiana from France.[6]Thwaites, 7:228.

This was hot stuff, fresh off the boat from Paris. All winter Robert Livingston, the American ambassador to France, had been trying to get Napoleon to sell the port of New Orleans. Then on 11 April 1803, the French foreign minister abruptly asked Livingston whether he’d take the whole of Louisiana. Livingston’s report of this offer arrived in Washington on 9 June, and Lewis learned of it just before composing his invitation to about Clark. The secret was preserved, more or less for about three weeks only.[7]Rumors of expanded negotiations for Louisiana were current in America before any official announcements. On 22 June 1803, The Guardian of Freedom newspaper in Frankfort, KY, printed part of “a … Continue reading Word of the Louisiana treaty’s actual signing reached Jefferson on 3 July, and the next day’s National Intelligencer broke the news under a headline of “Official.”

The impulse for secrecy seemed excessive in other respects, however. Lewis’s invitation to Clark also suggested a nonsensical cover story about the expedition’s destination. In recruiting men for the party, Clark was to fib that “the direction of this expedition is up the Mississippi to its source, and thence to the lake of the Woods.” That whopper originated with Jefferson, who gloated that “it satisfies public curiosity and masks sufficiently the real destination.”[8]Thwaites, 7:219.

Why? The governments of Britain, France and Spain already knew the real destination, if not the real purpose, and the Federalists in Congress knew everything. Moreover, Jefferson spread the cover story haphazardly, telling the Missouri truth to scientific cronies in Philadelphia and Paris, and the Mississippi fib to James Monroe and others who might actually need to know the “secret.” Picked as a special envoy to head the New Orleans negotiations in Paris, Monroe could have expected the President’s full trust. Yet on 25 February, Jefferson sent Monroe the misleading news that “Congress has given authority for exploring the Missisipi, which however is ordered to be secret.”[9]Jefferson to Monroe, 25 February 1803 in Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress.

At best, the cover just caused confusion. A month after Congress acted, the Philadelphia Aurora ran a rather garbled version of the Mississippi cover story: “It is reported that captain Lewis, the president’s private secretary, is to proceed in a few weeks on a journey towards our south western frontier, and that its object is of a political nature.” The story speculated that his political business “merely concerns our own territory, to which it is believed the journey of captain Lewis will be confined.”

Public News

Newspapers of that day freely reprinted each other’s news, so that 23 March 1803 story in Philadelphia may have circulated on the Western frontier. In his 18 July 1803 letter accepting Lewis’s invitation, Clark said that as a recruiter he was “holding out the Idea as stated in your letter—The subject of which has been mentioned in Louisville several weeks ago.”[10]Thwaites, 7:259. From that, however, it’s hard to know what destination Louisville was gossiping about.

On 29 August 1803, as Lewis was about to head down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh, a Louisville paper reported: “An expedition is expected to leave this place shortly, under the direction of Capt. William Clark and Mr. Lewis, (private secretary to the President) to proceed through the immense wilderness of Louisiana to the South or Pacific Ocean.”[11]Reprinted in the Philadelphia Aurora, 20 September 1803, page 2. The story’s source could only have been Clark, who by that time felt free to talk more openly.

By October Lewis had joined Clark in Louisville, and it was clear the President’s secretary now was doing the talking. In mid-November the Aurora printed this story without other attributions:

LOUISVILLE (Ken.) October 29. Captain Clark and Mr. Lewis left this place on Wednesday last, on their expedition to the Westward. We have not been enabled to ascertain to what length this route will extend—as when it was first set on foot by the President, the Louisiana country was not ceded to the United States, it is likely it will be considerably extended—they are to receive further instructions at Kahokia. It is, however, certain that they will ascend the main branch of the Mississippi as far as possible; and it is probable they will then direct their course to the Missouri, and ascend it. They have the iron frame of a boat, intended to be covered with skins, which can, by screws, be formed into one or four, as may best suit their purposes. About 60 men will compose the party.[12]Aurora, 17 November 1803, 2.

In talking to the Kentuckians, Lewis perhaps was trying to save the government’s credibility: in telling our original Mississippi story, we merely neglected to say we would also go up the Missouri. The reference to Lewis’s cherished iron-framed boat was a dead giveaway to the story’s source.

Notes

| ↑1 | Washington National Intelligencer, 19 January 1803, 2. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Reuben Thwaites, ed. (New York: Antiquarian Press edition, 1959), 7:208-209. |

| ↑3 | Carlos Martinez de Yrujo to Pedro Cevallos, 31 January 1803 in Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:14n. |

| ↑4 | Jackson, 1:15. |

| ↑5 | National Intelligencer, 23 February 1803, 3. |

| ↑6 | Thwaites, 7:228. |

| ↑7 | Rumors of expanded negotiations for Louisiana were current in America before any official announcements. On 22 June 1803, The Guardian of Freedom newspaper in Frankfort, KY, printed part of “a letter from Bordeaux, dated 24 April, stating: “It is even said there is no doubt about the cession of Louisiana to the U. States, on condition that the latter settle all claims of their individuals against the French Republic, and pay 3 millions of dollars in the bargain.” |

| ↑8 | Thwaites, 7:219. |

| ↑9 | Jefferson to Monroe, 25 February 1803 in Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. |

| ↑10 | Thwaites, 7:259. |

| ↑11 | Reprinted in the Philadelphia Aurora, 20 September 1803, page 2. |

| ↑12 | Aurora, 17 November 1803, 2. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.