The concept, purpose, and pre-requisites of an exploration of the American Northwest emerged during the Age of Enlightenment. The Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery was directed by President Thomas Jefferson to not only find and map a water passage between St. Louis and the Pacific Ocean, but to describe the native nations they encountered. They were to also describe its climate and find “objects worthy of notice” such as plants, animals, and “mineral productions.”[1]Jefferson’s Instructions to Lewis in Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), … Continue reading

Because the two commanders were the first to describe in writing many species new to science, Clark and Lewis would become known as “Pioneering Naturalists”[2]For more see, Paul R. Cutright, Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Naturalists (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1989 First Bison Books printing). and their work in the emerging fields of botany, ethnography, geography, geology, and zoology are now considered classics of early American scientific literature.

An Age of Enlightenment

Much of the daily work of the two captains was inspired by a set of transcendental values grouped under the rubric of Enlightenment philosophy—to observe, describe, and name all the universe’s constituent elements.

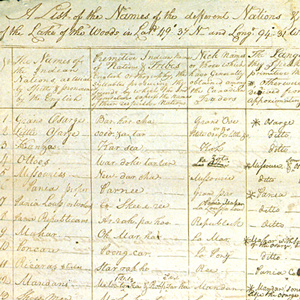

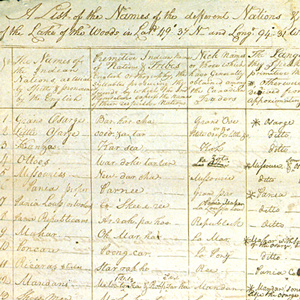

Ethnography

Nearly all the “discoveries” of the Lewis and Clark Expedition were already found by those living there and would be found again by Euro-Americans soon after. Their ethnographic data, on the other hand, provides us with a snapshot in time that can never be replicated.

The Dictionary of Bias-Free Usage remonstrated that “only by a strange twist of white ethnocentrism can one be considered to ‘discover’ a continent inhabited by millions of people.” Political correctitude might suggest that we simply drop the word discovery from our Lewis and Clark lexicon, and just speak of the captains as explorers.

For nearly 100 years, the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s full contribution to natural science was underpublished and a disappointment to many scientists expecting to learn more about the natural history of the regions explored. When it came to the mosquito, these naturalists were doubly disappointed.

Birds of the Expedition

The journals identify 134 species of birds with reasonable certainty and the President himself was an enthusiastic birdwatcher.

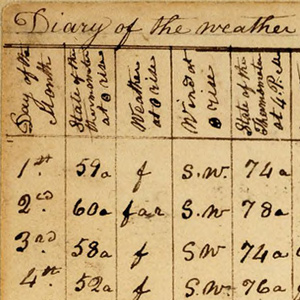

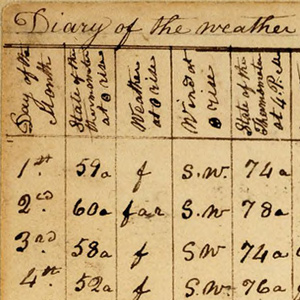

President Jefferson naturally was curious about weather conditions in the newly acquired expanse of Louisiana, and weather observations were on the long list of assignments for his exploring team. Jefferson instructed Lewis to record climate data observed on the trip.

Geology

The Missouri River exposed rock formations that were geologically diverse, distinctly colored, rich in mineral content, and in some places, dramatically distinguished by steaming and smoking hot earth that beckoned to be investigated.

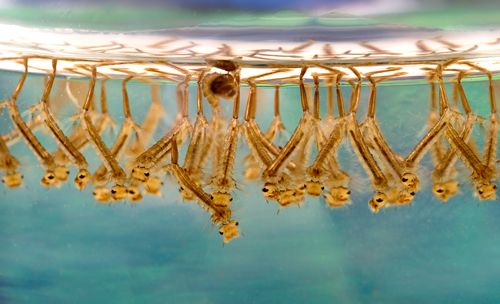

Insects

President Jefferson directed Lewis to observe seasonal transitions as they are marked by the “times of appearance of particular birds, reptiles or insects.”

Fish and Reptiles

Salmon as encountered by the Lewis and Clark Expedition and used by Native Americans are presented here along with eulachon, turtles, and rattlesnakes.

Geography

More than anything else, the objective of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was to lay claim to the new territory, and map it.

Related Naturalists

As describers of the natural world they encountered on the expedition, Lewis and Clark influenced—and were influenced by—several people who could now be called naturalists.

Mammals

“Meriwether Lewis contributed importantly to the development of American Zoology by making the first faunal studies in the newly acquired Louisiana Territory and by heeding Jefferson’s directive to observe ‘the animals of the country generally, & especially those not known in the U.S.'”

Plants of the Expedition

The more than two hundred specimens that reached Philadelphia signified the richness of the flora of the Pacific Northwest and particularly the states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Western Montana.

Medicine on the Trail

From major crisis such as the death of Sgt. Floyd, Lewis’s gunshot wound, and the illness of Sacagawea to minor events such as sexually transmitted diseases, mosquito-born illnesses, and deep cuts, the medical aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition provide an interesting topic of study.

“Late at night we were awaked by the sergeant on guard to see the beautiful phenomenon called the northern light….” What did Meriwether Lewis and William Clark understand about the aurora borealis? Scientific theories of their time may sound a bit fanciful today.

Influence on Science

The captains’ careful observations of the geography, natural history, and ethnography of the American west and Pacific Northwest influenced many scientists who built on their work.

Notes

| ↑1 | Jefferson’s Instructions to Lewis in Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 61–63. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For more see, Paul R. Cutright, Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Naturalists (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1989 First Bison Books printing). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.