Essentially, a bench plane is a chisel locked into a holder or “stock” of a hard wood such as beech. The chisel, or blade, is called the iron. The beveled and sharpened bottom edge of the iron, called the bezel or basil, may be straight, simply curved, or in two linked convex and concave curves for use in shaping moldings around doorways and windows.[1]James Smith, The Panorama of Science and Art: Embracing . . . the Methods of Working in Wood and Metal. . . . , 2 vols. (Liverpool: Nuttall, fisher and Co., 1815), 1:109-10, 112.

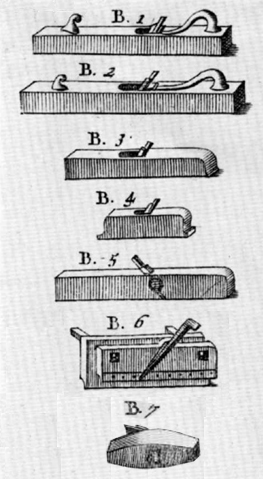

There are six planes in a joiner’s basic kit, often used in the following order:

- Fore plane or jack plane: Its blade, with flattened thumbnail curve (look at your own thumbs), cuts deeply to remove rough and uneven surface material;

- Jointer plane: Flattens the surface;

- Strike-block plane: Used for cross-grain cuts;

- Smoothing plane: Prepares the surface for finishing;

- Rabbet plane: Cuts a groove of controlled width and depth on the edge of a board;

- Plow plane: Cuts a narrow channel on the edge of a board, to admit the narrowed edge of another board that has been trimmed with a rabbet plane.

- Smoothing plane: Prepares the surface for finishing;[2]Joseph Moxson, Mechanick Exercises, 3rd ed., London, 1703; via Peter C. Welsh, Woodworking Tools 1600-1900, Smithsonian Institution, Contributions from The Museum of History and Technology, Paper 51.

A full set of planes may consist of as many as 14 different instruments.

Carpenters and Joiners

By the middle of the 18th century the varied disciplines of woodworking, long kept separate by the power of the guilds of artisans or craftsmen guilds that had arisen in the 12th century, were reorganized into two main types of general work, carpentry and joinery. A house carpenter worked on-site outdoors, with hammers, saws and axes; he framed-in houses and shops, and completed exterior work. A joiner was skilled in the shaping of pieces of wood with bench-planes, chisels and augers, and joining them together without metal fasteners to make fittings and furniture of all sorts. A house joiner would have been experienced in interior finish work, including stairways, doorways, and window frames, as well as decorative panelings, moldings, and wainscottings.[3]Elizabeth A. Davison, The Furniture of John Shearer, 1790-1820: A True North Britain in the Southern Backcountry (Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira Press, 2011), 10-11.

Notes

| ↑1 | James Smith, The Panorama of Science and Art: Embracing . . . the Methods of Working in Wood and Metal. . . . , 2 vols. (Liverpool: Nuttall, fisher and Co., 1815), 1:109-10, 112. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Joseph Moxson, Mechanick Exercises, 3rd ed., London, 1703; via Peter C. Welsh, Woodworking Tools 1600-1900, Smithsonian Institution, Contributions from The Museum of History and Technology, Paper 51. |

| ↑3 | Elizabeth A. Davison, The Furniture of John Shearer, 1790-1820: A True North Britain in the Southern Backcountry (Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira Press, 2011), 10-11. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.