Clark Waits

The Partnership Begins

© Michael Haynes, https://www.mhaynesart.com. Used with permission.

As the days grew shorter and cooler, William Clark must have worn a path to the Louisville landing. He probably had received Lewis’s letter of 28 September 1803, predicting his arrival before the letter’s, about 6 October 1803 or so. The barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) could be expected to heave into site at any moment. Since receiving his friend’s invitation on 17 July, Clark had devoted his time, energy, and abilities to preparing for the expedition. Lewis’s delay in reaching Louisville probably only served to heighten not only Clark’s, but also the recruits’ and area residents’ anticipation. Finally, on 14 October 1803, Lewis arrived! Clark, who had spent most of the summer in Louisville preparing for the expedition, almost certainly was there to greet his partner in discovery. A study of their correspondence that summer clearly establishes their intention to meet in Louisville. It is scarcely credible to think that he would not have been keeping a close watch upstream and at the landing for his friend. Eminent Lewis and Clark historian Donald Jackson believed so, writing in Thomas Jefferson and the Stony Mountains that “Clark met Lewis joyfully at Louisville.”[1]Donald Jackson, Thomas Jefferson & the Stony Mountains: Exploring the West from Monticello (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 145. There is confusion regarding where Lewis and Clark … Continue reading

No Journal Entries

Lewis’s “Leather Boat” Makes News

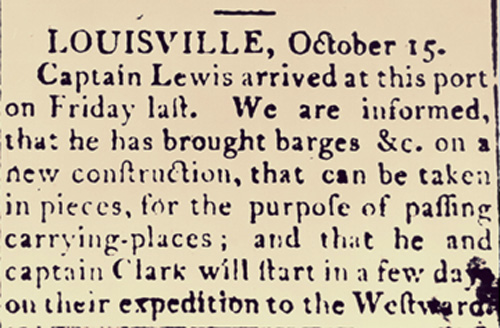

The Kentucky Gazette, Lexington, 1 November 1803

Courtesy the Filson Historical Society, Louisville.

Transcription: Captain Lewis arrived at this port on Friday last. We are informed that he has brought barges &c on a new construction, that can be taken in pieces for the purpose of passing carrying-places; and that he and captain Clark will start in a few days on their expedition to the Westward.

The second sentence refers to Lewis’s “experiment,” the 30-foot-long iron-framed, hide-covered collapsible boat Lewis himself had designed, and the construction of which he had personally supervised at Harpers Ferry the previous spring. It was a matter of great pride and high expectations.

Lewis’s account of making his way downriver over the seemingly endless riffles and visits to towns soon ended. He described a visit to Grave Creek Mound, a major Indian burial mound below Wheeling, as well as a stop at Marietta. But four days after leaving Marietta and having routinely recorded towns visited, river conditions, and distances traveled until then, Lewis abruptly discontinued his Eastern Journal. The last entry is dated 18 September 1803.

Why he stopped keeping the journal isn’t known. From 18 September until the 11 November 1803 arrival at Fort Massac on the lower Ohio, there is a gap. It is most unfortunate that there is not a daily log of what happened during this interim. Much must be pieced together from other sources, some must be deduced from evidence, and some facts remain a mystery. Information regarding Lewis’s visits at Maysville and Cincinnati; his stop at Big Bone Lick for fossil specimens for President Jefferson; his arrival at Louisville and meeting with Clark; his estimate of the men Clark had recruited; the Corps’ thirteen-day stay at the Falls of the Ohio and why it was delayed there that long; the departure from Clarksville; and the other towns the explorers visited between the Falls and Fort Massac–all remains fragmentary or unknown to this day.

So much more would be known if Lewis had maintained his journal or if Clark had begun a journal upon leaving the Falls. This foreshadowed Lewis’s journal keeping practices on the expedition–gaps for weeks and months at a time–but was uncharacteristic of Clark, who rather faithfully kept a journal or memorandum book while on trips. If he did keep a journal or any notes of the trip down the Ohio they have never been found nor their existence even hinted at.

What we do know after 18 September 18 is that the lower on the Ohio that Lewis descended, the more navigable the river became, even if still very low. About 24 September 1803, Lewis arrived at Maysville and on the 28 September 1803 he reached Cincinnati. He spent a week at the future Queen City, resting the men, visiting old friends, learning about and viewing animal bones and fossils from Big Bone Lick courtesy of Dr. William Goforth, and writing to Jefferson and Clark. On 1 October 1803, he dispatched the boats to Big Bone Lick, and then followed himself three days later via land. Lewis noted in his letter of 3 October 1803 to the President that the low water would require the barge three days to travel the fifty-three river miles to the lick, while he would spend less than a day going the seventeen land miles. Several days were apparently spent at Big Bone Lick in collecting specimens for Jefferson. Unfortunately, they never made it to him. The following year, sitting in crates on a boat at the Natchez dock, they sank in the Mississippi River.[2]Jackson, Letters, 1:126-132.

Why the Delay?

The Clark home known as “Mulberry Hill,” built under the supervision of Jonathan and George, William’s older brothers in 1783-84, by slaves who included Old York, the father of William Clark’s personal slave, who was also called York. The rest of the Clark family, including 14-year-old William, arrived here in March 1785. In 1799 William inherited the house from his father, and in 1803 sold it to Jonathan. It remained in the Clark family until its collapse in the early 1900s. This photo was taken about 1890.

The 15 October 1803 edition of the Louisville Farmer’s Library newspaper reported Lewis’s arrival the day before. The report was reprinted by the Lexington Kentucky Gazette and it is this source that survives today: “LOUISVILLE–Captain Lewis arrived at this port on [14 October 1803] . . . he and captain Clark will start in a few days on their expedition to the Westward.” More than “a few days” passed, however, before the foundation of the Corps began their journey west. It wasn’t until 26 October 1803, thirteen days after Lewis’s arrival, that they left.[3]Kentucky Gazette, 1 November 1803 and 8 November 1803. No issues of the Farmer’s Library from those dates are known to be extant. During that time period the Farmer’s Library was … Continue reading

Why the delay? A few days became a week and a week became almost two weeks. Did something happen to the barge in going through the Falls? Thomas Rodney went through the Falls three days after Lewis and Clark in a bateau with less than half that boat’s draft. He described a terrifying trip through the churning, rock-strewn channel–even with James Patten, the Falls’ most experienced pilot, guiding the craft.[4]Smith and Swick, pp. 124-25. James Patten was one of Louisville’s original settlers. He was also the former father-in-law of Nathaniel Hale Pryor. His daughter Peggy married Pryor in 1798 but … Continue reading Did William Clark perhaps suffer a bout of illness? Soon after leaving, Clark fell ill not once, but twice. It’s possible, but he doesn’t reference his illness on the Ohio and Mississippi as being relapses of an earlier malady.[5]James J. Holmberg, editor, Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark, with a Foreword by James P. Ronda (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), pp. 60, 64-65n. Perhaps more time to evaluate and enlist the recruits? That’s unlikely. Clark had enlisted three of “the best woodsmen & Hunters, of young men in this part of the Countrey” by the time Lewis arrived, and the other “Nine Young Men from Kentucky” were enlisted from 15 October 1803 to 20 October 1803.[6]Jackson, 1:117. Was the delay another of Lewis’s emerging trends of procrastinating or staying somewhere longer than he stated he intended? Maybe one day we’ll know.

Tasks

While at the Falls of the Ohio, Lewis and Clark are known to have spent their time enlisting the other six members of the “Nine Young Men,” making other preparations, and visiting.

From their base at Clarksville, the captains went back and forth between the Clark farm and Louisville. On the evening of 17 October 1803, they visited Rodney on his boat tied up at the Louisville waterfront and enjoyed a glass of wine with him.[7]Smith and Swick, p. 124. They most likely ventured out to Jonathan Clark’s Trough Spring estate and to Locust Grove, home of Clark sister and brother-in-law, Lucy and William Croghan.

Over the Falls

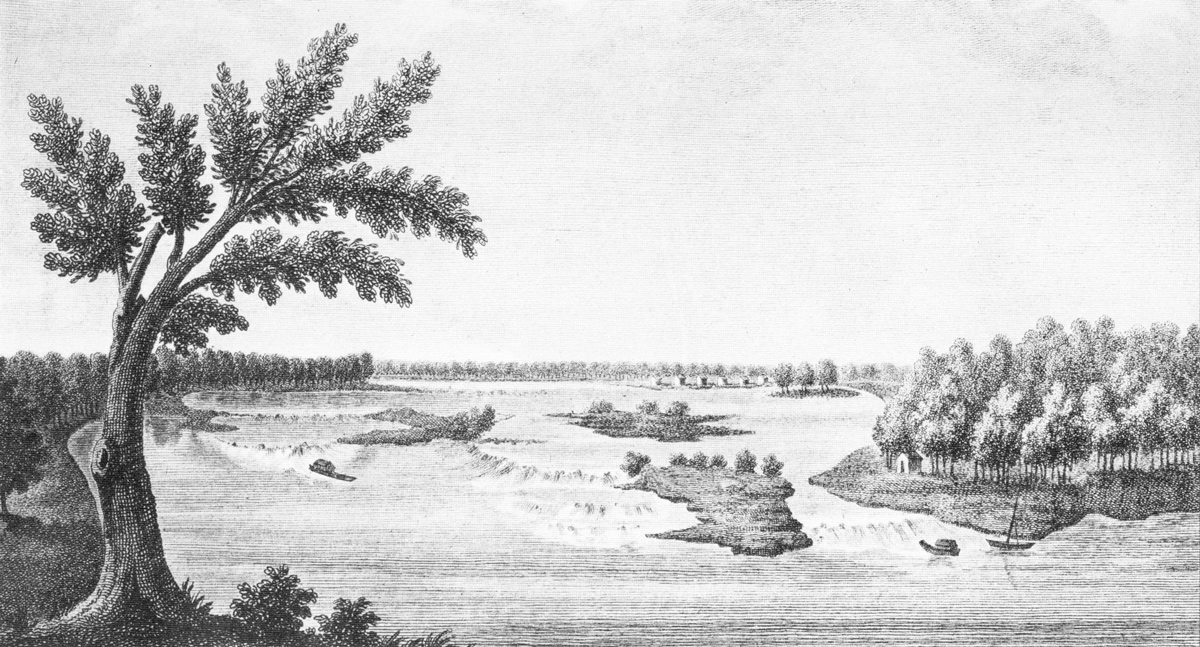

The French explorer General George Henri Victor Collot (1750-1825) came to America in 1796 on a secret mission to investigate the possibilities of inciting settlers on the western frontier to rebel against the U.S. government and join the French empire. On orders of Arthur St. Clair, the American governor of the Northwest Territory, Collot was arrested for espionage when he reached Cahokia, and was deported.

As recounted in his book, Voyage dans Amerique Septentrionale (Voyage in North America), Collot’s description of the “Rapids or Falls” of the Ohio at Louisville suggests the difficulties and dangers Lewis and Clark may have encountered in October 1803. They, like Collot, were obliged to hire a pilot to avoid the hazards:

Near the fall the islands and rocks by which it is formed take up nearly three quarters of the bed of the river, and fill up and obstruct all the side on the southeast; the waters have no other passage in dry seasons than on the side of the north-west, but as they are much confined, and the plane over which they roll is very shelving, and they have to make their way across every obstacle, they rush along with the greatest impetuosity and violence.

On the side which is obstructed there are only five or six inches of water, and often the bank of stones is dry. In the channel where the boats pass, the depth of water varies, but is never less than from four to five feet: this depth would become more than sufficient to pass at all times with security, if the windings of the channel were not so abrupt and numerous, and the current so strong; but in the present state of the passage, the pilot has scarcely time to steer, or the boat to change its direction.[8]Collot, 1:151-152.

Despite the pilot’s skill and attention, Collot’s boat struck a rock and scraped off three feet of the keel. “In the season of floods,” Collot remarked, “these inconveniences disappear, and during eight months in the year there is water enough to pass the double channel with all kinds of boats.”[9]Ibid., 152.

The so-called Falls of the Ohio consisted of a series of rapids and cascades that dropped the river a total of twenty-four feet in two miles.

Notes

| ↑1 | Donald Jackson, Thomas Jefferson & the Stony Mountains: Exploring the West from Monticello (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 145. There is confusion regarding where Lewis and Clark met to actually form their famous partnership. Was it Louisville or Clarksville? The great weight of evidence places the meeting in Louisville. It was in Louisville that Clark was spending much of his time preparing and recruiting for the expedition and wrapping up his affairs. His family and friends lived in and around Louisville and he spent time with them as well. Their correspondence clearly states their intention to join forces in Louisville. How is it then that Clarksville is sometimes cited as the meeting place? The basis for it seems to be a geographical error made by Roy Appleman in his Lewis Clark: Historic Places Associated with their Transcontinental Exploration (1804-1806). Appleman placed Louisville at the foot of the Falls of the Ohio, directly across the river from Clarksville, instead of at the head of the Falls where it actually was in 1803 (later growth resulted in it stretching downstream to well below the Falls). When Lewis reached the Falls, Appleman assumed he went through the Falls in order to reach either town. Since Clark had moved across the river to Clarksville earlier in 1803, Appleman believed it was a simple matter of Lewis’s taking a right to Clarksville instead of a left to Louisville and then going in search of his partner (see Appleman, 52). Later writers, including Stephen Ambrose, have relied on Appleman as their source for the explorers’ meeting and this error continues to be perpetuated today. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jackson, Letters, 1:126-132. |

| ↑3 | Kentucky Gazette, 1 November 1803 and 8 November 1803. No issues of the Farmer’s Library from those dates are known to be extant. During that time period the Farmer’s Library was published on Saturdays which corresponds to the date of the reports picked up by the Gazette. Both papers were weeklies, as were most newspapers at that time. |

| ↑4 | Smith and Swick, pp. 124-25. James Patten was one of Louisville’s original settlers. He was also the former father-in-law of Nathaniel Hale Pryor. His daughter Peggy married Pryor in 1798 but is believed to have been dead by the fall of 1803. |

| ↑5 | James J. Holmberg, editor, Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark, with a Foreword by James P. Ronda (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), pp. 60, 64-65n. |

| ↑6 | Jackson, 1:117. |

| ↑7 | Smith and Swick, p. 124. |

| ↑8 | Collot, 1:151-152. |

| ↑9 | Ibid., 152. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.