Henry Dearborn was Secretary of the War Department throughout the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which was a military corps through and through. He made several decisions critical to its success, and he was the ultimate decider that gave Clark his military rank of lieutenant.[1]Extracted from Sherman L. Fleek, “The Army of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 30 No. 4, November 2004, 8–14. The original full-length article is available at our sister site, … Continue reading.

Secretary of War

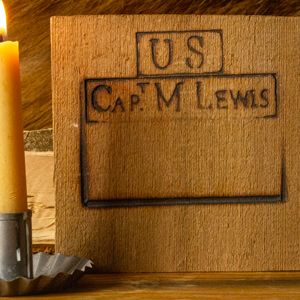

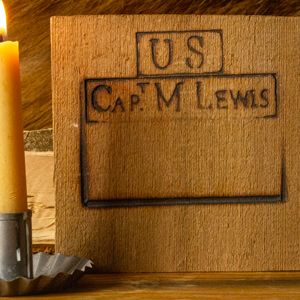

Henry Dearborn served as President Thomas Jefferson‘s secretary of war for the entire eight years of his administration. A native of New Hampshire, he came to the job with a wealth of military experience acquired during the Revolutionary War—he had fought at Bunker Hill, Quebec, and Saratoga, and later served on Washington’s staff. A hands-on administrator with a penchant for detail, he peppered Joseph Perkins, the superintendent of the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia with suggestions about the design of the U.S. Model 1803 rifle. Meriwether Lewis carried Dearborn’s instructions to Perkins when he visited the armory to outfit the expedition. Although the Model 1803 went into production too late to be part of the Corps of Discovery’s arsenal, some of its design features (including a half stock and relatively short barrel) were probably incorporated into the rifles issued to Lewis[2]See on this site The Muskets and Rifles. Dearborn also came up with an idea, ahead of its time, for highly mobile “flying” artillery, which would be used to great effect forty years later during the Mexican War.[3]Theodore J. Crackel, Mr. Jefferson’s Army: Political and Social Reform of the Military Establishment, 1801–1809 (New York: New York University Press, 1987), 78–9.

It was under Dearborn, too, that the army began the systematic exploration of the American West—an enterprise that was to last the better part of a century and for which the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with its emphasis on natural history and cartography, was a prototype. In 1805, while the Corps of Discovery was following the Missouri to its source on the Continental Divide, Lieutenant Thomas Freeman led a party up the Red River on the southern plains—the Freeman-Custis Expedition and Lieutenant Zebulon Pike explored the headwaters of the Mississippi. In 1806, Pike and Lieutenant James Wilkinson[4]The son of General James Wilkinson. led a detachment up the Arkansas River to the Colorado Rockies. Subsequent decades were marked by the expeditions of other soldier-explorers, including Major Stephen H. Long (1819-20), Lieutenant John C. Frémont (1842, 1843-33, 1845), and Lieutenant William H. Emory (1846).[5]William H. Goetzman, Army Exploration in the American West, 1803-1863 (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1991). James P. Ronda, Beyond Lewis & Clark: The Army Explores the West … Continue reading

Dearborn and Clark’s Commission

Dearborn has come in for criticism for his role in the confused affair of Clark’s commission. As every student of Lewis and Clark knows, Jefferson agreed to Lewis’s request to offer his friend a captaincy in the Corps of Engineers, but to the chagrin of both men, the commission eventually authorized was a second lieutenant’s in the artillery.[6]When Clark left the army in 1796 he held the rank of lieutenant—not, it is sometimes erroneously reported, a captain. Nor was he a first lieutenant. At the time, the army didn’t distinguish … Continue reading Adding insult to injury, this was a grade below first lieutenant, the rank Clark had held when he left the army in 1796. Clark accepted Lewis’s invitation and began recruiting men for the expedition in early August of 1803, but the commission that gave him the authority to do so was effective March 26, 1804, the date it was approved by the Senate as part of a list of nominations from the War Department.[7]Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:172–73. The late date of the commission denied Clark seniority important for future promotion, and because there was no provision for back pay, he was left uncompensated for his first eight months of service.

Lewis’s biographer Stephen E. Ambrose offered several hypotheses for the government’s failure to grant Clark his promised rank: Jefferson and Dearborn overlooked the details, or Jefferson wanted Lewis in “sole command.”[8]Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), 135. Commissioning Clark a captain would have jumped him ahead of lieutenants on the active-duty rolls, and it could be that Dearborn and Jefferson simply bowed to the army’s seniority system. But there was a bigger problem, as William E. Foley points out in his biography of Clark: “In fairness to Dearborn he had to operate under the constraints of an 1802 statute designed to shrink the military establishment during peacetime, and there were no vacant captain’s slots at the time.”[9]William E. Foley, Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004), 70. Ironically, this statute—the Military Peace Establishment Act—had been passed at Jefferson’s behest, and it would have taken another act of Congress to create a captain’s slot for Clark.

Presumably at Dearborn’s direction, the War Department eventually made at least partial amends for its shoddy treatment of Clark. Army pay records indicate that he was promoted to first lieutenant in February 1806, while the Corps of Discovery was still on the Pacific. Following the expedition’s return, when the department computed Clark’s back pay it did so from August 1, 1803, thereby restoring both the early pay due him (albeit as a second lieutenant) and his seniority. In addition, on Jefferson’s orders the War Department made up the difference in total compensation (pay plus subsistence allowance) between a lieutenant and a captain, and like all members of the expedition, Clark was also awarded double pay for his service and a grant of land (in his and Lewis’s case, 1,600 acres west of the Mississippi).[10]Arlen J. Large, “‘Captain’ Clark’s Belated Bonus,” We Proceeded On, November 1997, 12-14, lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol23no4.pdf#page=10; Jackson, 1:363-364 and 375–76. Clark’s total pay package for his 43 months with the corps amounted to more than $4,000, equivalent in today’s currency to about $60,000.[11]“Economic History Services” (http://eh.net/hmit/ppowerusd), accessed 6 September 2004.

Dearborn also asked the Senate to promote Clark to lieutenant colonel in the Second Regiment of Infantry—a jump of three grades. His request was presumably intended to recognize Clark’s contributions to the expedition, although Dearborn must have realized it had little chance of approval. Some senators were apparently unwilling to buck the seniority system, and the request was rejected.[12]Jackson, 1:376n; Foley, 158.

[For Clark’s perspective on his rank, see on this site Clark’s Military Rank by Joseph Mussulman.]

The Letters of Henry Dearborn

These pages include letter excerpts to or from Henry Dearborn related to the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

February 15, 1803

Pressing Indian affairs

In Washington City, President Jefferson urges the War Department to negotiate for Native Nation lands in the Illinois and Mississippi Territories before France assumes control of New Orleans and Louisiana.

In Washington City, President Jefferson urges the War Department to negotiate for Native Nation lands in the Illinois and Mississippi Territories before France assumes control of New Orleans and Louisiana.

February 19, 1803

Stoddard's orders

Captain Amos Stoddard is ordered to proceed to Kaskaskia as part of a military buildup along the Mississippi. President Jefferson has little hope of giving Thomas Rodney a federal appointment.

March 14, 1803

Appropriations

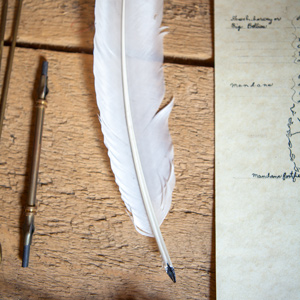

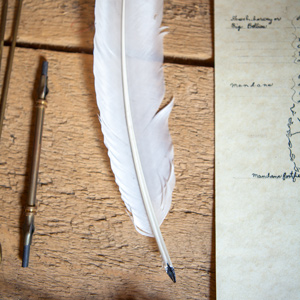

In Washington City, the expedition’s appropriation is made public, and a warrant for $2500 is issued. Lewis is granted access to the Harpers Ferry armory and Israel Whelan, “Purveyor of Public Supplies”.

March 24, 1803

One thousand dollars

In Washington City, the Secretary of the War Department, Henry Dearborn, informs his purchasing agent Israel Whelan that he will receive $1000 to purchase expedition supplies for Meriwether Lewis.

June 30, 1803

Whelan's statement

U.S. Army records summarize the purchases made while Meriwether Lewis was in Philadelphia. Now in Washington City, Lewis also records a payment of $1000 to his primary purchasing agent, Israel Whelan.

July 2, 1803

Dear Mother

With departure from Washington City imminent, Meriwether Lewis writes to his mother Lucy Lewis Marks. The War Department requests boats and soldiers from the U.S. Army.

August 3, 1803

Thanks to Clark

From Pittsburgh, Lewis writes a letter thanking Clark for joining the Western Expedition. He asks Clark to find interpreter John Conner, and to stop engaging recruits until he arrives in Louisville.

October 5, 1803

Big Bone Lick

Lewis is likely at Big Bone Lick collecting fossils and fellow travelers Thomas Rodney and Nicholas Cresswell describe the diggings that he saw. Elsewhere, the U.S. Army expects problems with Spain.

March 1, 1804

Quarters and stores

At Wood River, Illinois, the day begins with sub-zero temperatures. While they are in St. Louis, the captains leave specific orders for Sgt. Floyd regarding quarters and stores.

June 3, 1804

Mosquitoes and ticks

At the mouth of the Osage, mosquitoes and deer ticks vex Clark, and Lewis collects a specimen of ground plum. Late in the day, the boats move up to the mouth of the Moreau east of present Jefferson City.

July 18, 1804

Geology and botany

Clark remarks on the region’s geology and Lewis collects a partridge pea specimen as they travel up the Missouri below present Nebraska City. At their evening camp, a stray Indian dog is fed.

June 13, 1805

"sublimely grand specticle"

At the Grand Fall, Lewis marvels at the “sublimely grand specticle”. Downriver, Clark gives Sacagawea a dose of salts. At Fort Massac, General Wilkinson has questions about the people sent to him in the barge.

June 15, 1805

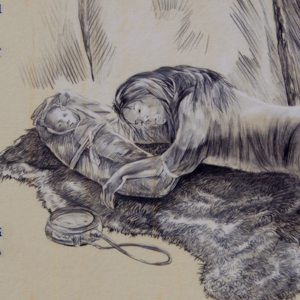

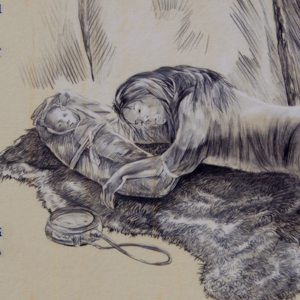

Sacagawea deteriorates

Below the Great Falls of the Missouri, Sacagawea‘s health deteriorates, and Charbonneau asks her to return home. Several miles ahead, Lewis fishes and describes a prairie rattlesnake in minute detail.

July 14, 1805

Launching the new canoes

Lewis remarks on the view of Square Butte from their canoe camp near present Ulm, Montana. Sgt. Ordway brings the remaining dugouts, the two new canoes are launched, and all is made ready for departure.

September 22, 1805

Bitterroot Mountain triumph

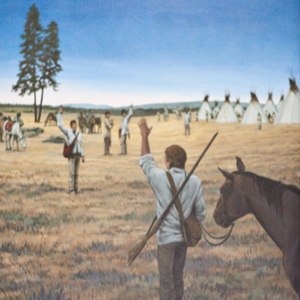

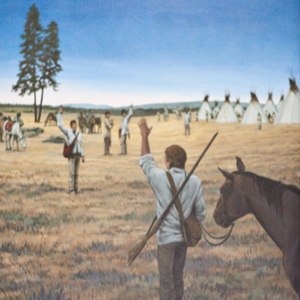

Lewis and the main party arrive at the Weippe Prairie villages “having tryumphed over the rocky Mountains”. Clark and Twisted Hair climb up from the Clearwater River and the two captains unite.

October 8, 1805

A canoe accident

On the Clearwater River, the paddlers navigate numerous rapids and pick up guides Twisted Hair and Tetoharsky. After a canoe accident at Colter’s Creek—present Potlatch River—travel abruptly stops.

April 9, 1806

Beautiful waterfalls

The flotilla moves sixteen miles up the Columbia River Gorge marveling at its many beautiful waterfalls. In Washington City, the Secretary of War deals with the unexpected death of Arikara Chief Too Né.

April 30, 1806

Crossing the sandy plain

The expedition sets out on the Travois Road passing through sagebrush and sand dunes. They camp on the Touchet River north of present Walla Walla. Lewis describes eating dog, river otter, and horse.

May 9, 1806

Horses and saddles found

The corps moves about six miles to Twisted Hair‘s small camp near present Nezperce, Idaho. The horses and saddles left with the Nez Perce last fall are found, and then, it begins to snow.

Notes

| ↑1 | Extracted from Sherman L. Fleek, “The Army of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 30 No. 4, November 2004, 8–14. The original full-length article is available at our sister site, lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol30no4.pdf#page=9 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See on this site The Muskets and Rifles |

| ↑3 | Theodore J. Crackel, Mr. Jefferson’s Army: Political and Social Reform of the Military Establishment, 1801–1809 (New York: New York University Press, 1987), 78–9. |

| ↑4 | The son of General James Wilkinson. |

| ↑5 | William H. Goetzman, Army Exploration in the American West, 1803-1863 (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1991). James P. Ronda, Beyond Lewis & Clark: The Army Explores the West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003). |

| ↑6 | When Clark left the army in 1796 he held the rank of lieutenant—not, it is sometimes erroneously reported, a captain. Nor was he a first lieutenant. At the time, the army didn’t distinguish between first and second lieutenant; its lowest commissioned rank was ensign, the equivalent of second lieutenant. The army had abandoned the ensign rank by 1804 and replaced it with second lieutenant, its entry-level rank for commissioned officers. Ensign is still a rank in the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard. Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army from its Organization, September 29, 1789 to March 2, 1903, 2 volumes (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1903; reprinted, University of Illinois Press, 1965), 1:306. |

| ↑7 | Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:172–73. |

| ↑8 | Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), 135. |

| ↑9 | William E. Foley, Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004), 70. |

| ↑10 | Arlen J. Large, “‘Captain’ Clark’s Belated Bonus,” We Proceeded On, November 1997, 12-14, lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol23no4.pdf#page=10; Jackson, 1:363-364 and 375–76. |

| ↑11 | “Economic History Services” (http://eh.net/hmit/ppowerusd), accessed 6 September 2004. |

| ↑12 | Jackson, 1:376n; Foley, 158. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.