Early Years

No other botanical explorer in western North America is more famous than David Douglas. His name is associated with hundreds of western plants, and may also be found on mountains, rivers, counties, schools and even modern-day streets. He was a remarkable adventurer even though the fates were mostly unkind to his person.

He was born at Scone, near Perth, Scotland, in 1799. After attending school for a few short years, at eleven he began his botanical career at the garden estate of the Earl of Mansfield. For the next seven years, young Douglas worked on the estate under the strict tutorage of the head gardener, William Beattie, who disdained formal education. Upon completing his apprenticeship, Douglas moved to Valleyfield and the estate of Sir Robert Preston, where he tended a diverse variety of plants from around the world—those grown both indoors and out. He also had access to Sir Robert’s library and began again his education among these garden and botany books.

In the spring of 1820, Douglas obtained an appointment at the botanic garden at Glasgow University. A few months later a new professor of botany, William Jackson Hooker, was appointed, and he and Douglas began their long professional association.[1]Born in 1785, William Jackson Hooker, eventually Sir William Jackson Hooker, would move from Glasgow and become director of the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew in 1841. He would build it into one of the … Continue reading By 1821, Hooker and Douglas were in the field, with Douglas learning the fine art of pressing and drying plants. After two years together, Hooker recommended his young assistant to the Royal Horticultural Society of London. They were looking for a skilled gardener and collector to send to America.

North American Assignment

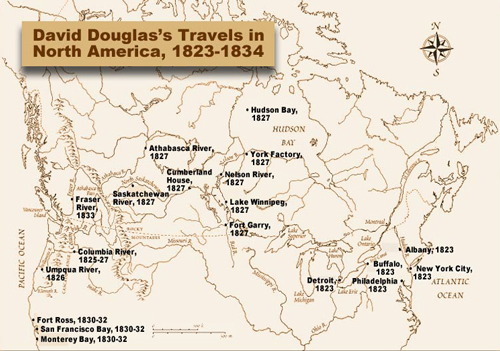

Scottish naturalist David Douglas made his first trip to North America in spring 1823, sailing from Liverpool to New York City as a raw collector. Assigned by the London Horticultural Society to assess new cultivars of soft fruit, the qualities of oak timber, and promising garden plants, the 24-year old son of a village stonemason proved energetic at his tasks and, perhaps more importantly, adept at dealing with a wide assortment of Americans who could help him perform them.

Over the course of the summer, Douglas tasted 24 different cultivars of peaches grown by an old Dutchman on Long Island, complained about the rootstock of a Flushing nurseryman, raided the New Jersey pine barrens for pitcher-plants, and matched oak species to barrel staves at an upstate cooperage. In between these adventures, the novice found time to accept some remarkable plums from Dr. David Hosack, who had served as attending physician at the Hamilton-Burr duel. He dug lady slipper orchids at a site suggested by New York governor DeWitt Clinton, just then in the midst of completing an important section of the Erie Canal.

By a lucky chance, he preserved the living slip of an Oregon grape plant grown from stock that the Lewis and Clark Expedition had picked up in the Pacific Northwest. By September Douglas was in southeastern Canada, looking as always for seeds and cuttings of fruit trees as well as wild woody plants. Perhaps as a sign of things to come, while Douglas was in a tree looking at a mistletoe one of his guides stole his coat, money, field books and a textbook.

American Connections

Douglas made important botanical connections while in the United States. In New York he met John Torrey, who was rapidly becoming the foremost botanist in the United States. Later in the fall of 1823, in Philadelphia, he encountered Thomas Nuttall. Together the two men sought out some of the rarer plants found near the city, with Douglas gathering seeds for his sponsor, the Royal Horticultural Society.

The results were minimal at best. Still, the Society, and in particular its secretary, Joseph Sabine, was impressed with the quality of the material sent back to London. Thus, when word came in the spring of 1824 that the Hudson’s Bay Company was willing to sponsor a collector along the Columbia River, Douglas was the immediate choice.

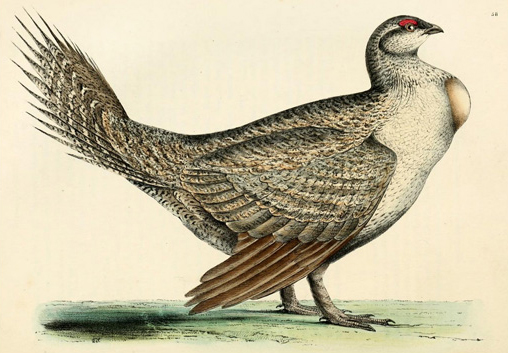

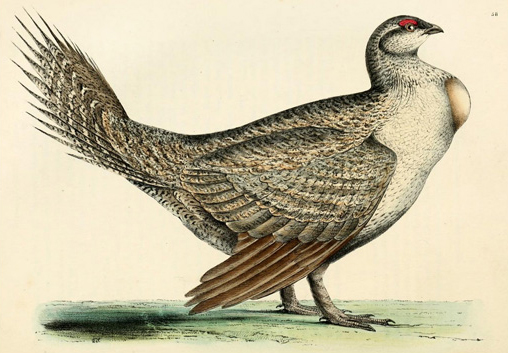

Sabine arranged for him to get three books: Frederick Pursh‘s Flora americae septiontrionalis, Nuttall’s The genera of North American plants, and François André Michaux‘s The North American sylva. The latter, published in three volumes (1817-1819), was an improved edition of the original French edition published earlier (1810-1813). Illustrated with 150 colored engravings, this work contained the latest information on western North American trees.[2]In 1793, François-André’s father, botanist André Michaux (1746-1802), offered his services to Jefferson and others in the American Philosophical Society to explore the West, and … Continue reading Overseeing Douglas’ study was the Society’s assistant secretary, John Lindley. As a final step in his education, Sabine sent Douglas to call upon Archibald Menzies. Thus, in the late spring of 1824, the two men who would come to play such important roles in the discovery and naming of Douglas-fir, [3]Pseudotsuga menzesii, came together for a chat over tea.

Douglas had a long-standing interest in the discoveries made by Lewis and Clark. He knew some of their discoveries from the English garden, and he had sought out others when he visited Philadelphia the year before. It is possible that when he visited Aylmer Bourke Lambert, he examined the collections used by Pursh to describe such new genera as Lewisia, Clarkia, and Calochortus.

Eastern Travels

Of the manners of this majestic animal I can say nothing, never having had an opportunity of seeing it alive.[4]David Douglas, “Observations of Two Undescribed Species of North American Mammalia,” Zoological Journal, 4 (1829), 332.

—David Douglas

During his three-month stay in the United States, Douglas steamed all the way west to Detroit and rode south as far as Wilmington, Delaware, but the touchstone of his first expedition turned out to be Philadelphia, long the center of natural science in the fledgling country. At the University of Pennsylvania he watched a master propagator work with seeds from the Long Expedition, which had only recently returned from the Colorado Rockies. Thomas Nuttall, who had made his own collecting trip up the Arkansas River and written the plant book that Douglas used as his main reference, took him on a visit to the famous Bartram Gardens on the Schuylkill River. There the niece of the recently deceased William Bartram presented him with seedlings from a sourwood tree that her uncle had brought back from his own legendary collecting foray into Georgia and Florida at the dawn of the American Revolution.

William Bartram had served as a key consultant for Thomas Jefferson during preparations for the Corps of Discovery, and David Douglas certainly had that expedition on his mind when he toured Charles Willson Peale‘s famous Philadelphia Museum. There the young collector was particularly taken with a bighorn sheep that the captains had shot on the Missouri River. Douglas may not have been quite as conscious of the fact that in 1804, as the Corps began to make their way to the Northwest, the German polymath Alexander von Humboldt had stopped by same museum on his way home from South America. Artist and proprietor Peale had personally escorted the man Charles Darwin later called “the greatest scientific traveler who ever lived”[5]Paul H. Barrett and Alain F. Corcos, “A Letter from Alexander Humboldt to Charles Darwin.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 27 (1972):161. to Washington D.C., where he was welcomed by Jefferson as a guest at the White House.

The president and Humboldt shared many common interests, and at least one later historian would compare the multifaceted approach Jefferson used in his Notes on the State of Virginia with Humboldt’s groundbreaking work in the realm of bio-geography.[6]Silvio Bedini, Thomas Jefferson: Statesman of Science. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1990), 490.

As David Douglas traveled extensively through the Pacific Northwest, California, and Hawaii over the years 1824-34, he sought to uncover the same kinds of deep connections within the physical world that Jefferson and Humboldt had pursued. Along the way, Douglas maintained the knack he first displayed in Philadelphia for serendipitously combining his everyday work as a collector with seminal characters and events. The course of Douglas’s journeys not only provides a backward glance into the context of early 19th century natural science, but also points forward toward the shaping of our modern landscape.

Collecting Conifers

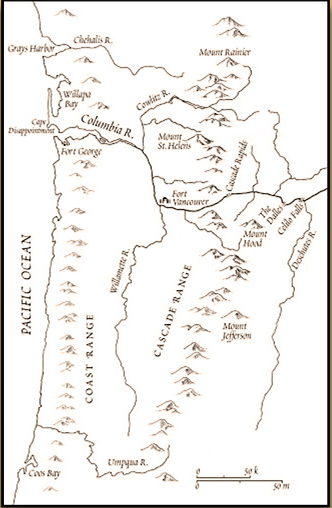

On the Pacific coast, the rewards for Douglas were immediate and numerous. Even though first Menzies and then Lewis and Clark had collected plants in the area, they had found only the obvious. Almost every day Douglas was in the field he was finding curious plants that proved to be new to science, and as he traveled up the Columbia River, the novelties became more common. Because he was working for the Royal Horticultural Society, Douglas had to collect flowering and fruiting material, and then often had to return to the area at a different time of the year to gather seeds. Instead of returning to London in 1826, as instructed by Sabine, Douglas decided to stay in America. There were too many new plants yet to be collected.

One of the collections he sent to England with the fall’s home-bound ship was the dried branches and needles of what he would call “Oregon pine,” which today is called Douglas-fir.

The year 1826 found Douglas deep inland, climbing the tall mountains of northeastern Oregon and various peaks in the Cascade Range. Late that year he collected seeds of as many trees, shrubs and flowers as he could find, but if he got cones and seeds of Douglas-fir, he did not mention them. Rain and snow made collecting impossible for the first three months of 1827, and then in late March he and a small party set out to return to England via Hudson’s Bay. Carrying all of his new collections, he and his crew traveled up the Columbia River and across the Rocky Mountains, reaching York Factory on the southwestern shore of the Bay on July 28.

Douglas spent two frustrating years in England, to which he returned on October 15, 1827. In a sense it was a productive time. He was able to describe the sugar pine, Pinus lambertianus (lam-bert-ee-AYE-nuss; the name means “in honor of Lambert”), the most distinctive discovery that he himself published. As for the other novelties, he left them for others to describe. In late October of 1829, Douglas headed back for the Columbia River as the pages of the Transactions of the Royal Horticultural Society and other journals were beginning to fill with the technical descriptions of the numerous new species of flowering plants he had already discovered.

Some eight months later, Douglas’s ship reached the smooth waters of the Columbia, and once again he was collecting in the Pacific Northwest. In a letter dated October 11, 1830, Douglas wrote Hooker that he was sending a special package of six conifers [See Douglas’s Six Firs], and apparently all with seeds. One of the six was Douglas-fir. He also indicated he was planning to go to California to collect the following year.

Final Years

It is difficult for one today to imagine the nature of the great, native forests of the Pacific Northwest that David Douglas walked through in late 1820s and early 1830s. It is equally difficult to comprehend the pain he endured to do it. Douglas was a gifted collector, but in the field he was often in trouble. He once fell on a nail that penetrated his leg under the kneecap. He nearly drowned in a glacier-fed river, losing his rifle, part of his collection, his journals, and his kit. He was weeks away from civilization with little but his wet clothes.

Some stories have an element of humor, as when he found his long-sought sugar pine in southern Oregon. He had long since become separated from the others he was traveling with, so only he and his dog gazed upon the great tree. The cones, ripe with seed, were so high that to get them he shot at them with his rifle. This attracted Indians—in warpaint. Crouching behind a downed giant of the very species he was studying, he pulled both pistols and his knives, and laid his rifle across the trunk. They agreed to talk, via Plains Sign Language, whereupon Douglas persuaded the Indians to gather cones in exchange for tobacco. While the Indians were out of sight looking for cones, Douglas grabbed a branch and two cones and ran. Those specimens are still extant and may be seen today in England.

Douglas grew blind in one eye, and his vision was slowly failing in the other, so perhaps that’s what caused his ultimate misfortune. While working on the island of Hawaii he fell into a bull trap had been dug on a well-used game trail to capture wild cows. Maybe he fell in first, and later the bull came along; maybe there was already a bull in the trap and the botanist fell in trying to look at it. In either case, when searchers came upon the site, his faithful dog was sitting near the edge of the pit, 34-year-old David Douglas was dead, and the bull had stopped mauling his body. It was 12 July 1834.

He was buried on the Island of Oahu; twenty-two years later a tombstone was erected, bearing his epitaph:

Hic jacet

D. DAVID DOUGLAS

Scotiâ, anno 1799 natus;

Qui,

Indefessus viator,

A Londinensi Regiâ Societate Horticulturali missus,

In Havaii saltibus

die 12â Julii, A.D. 1834

victima scientiae

Interiit.

“Sunt lachrymae rerum et mentem mortalia tangunt.” —Virg.

Translation: Here lies D. DAVID DOUGLAS, born in Scotland in the year 1799; who, an untiring traveler, sent by the London Royal Horticultural Society, died a victim of science in a mountain forest of Hawaii on the 12th day of July, 1834 A.D.

“There are tears of things and they touch the mortal mind.” —Virgil

Others would name the hundreds of new species Douglas found, often taking up the suggested names written on the tickets associated with each collection. It is impossible to venture anywhere in much of the American West without seeing a plant he collected, that he named, or that was named for him. In fact, in many places, all one needs to do is look at the forests on the higher mountains—there it will be, Douglas-fir, accounting for one-fourth of all the standing saw timber in the United States.

References

Coats, A. M. 1970. The plant hunters: Being a history of the horticultural pioneers, their quests and their discoveries from the Renaissance to the twentieth century. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Douglas, D. 1914. Journal kept by David Douglas during his travels in North America, 1823-1827. Royal Horticultural Society, London.

Hooker, W. J. 1836-1837. “A brief memoir of the life of Mr. David Douglas, with extracts from his letters.” Companion to the Botanical Magazine 2: 79-182 [in four parts].

McKelvey, S. D. 1955. Botanical explorations of the trans-Mississippi west, 1790-1850. Arnold Arboretum, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts.

Morwood, W. 1973. Traveler in a vanished landscape. The life & times of David Douglas, botanical explorer. Clarkson N. Potter Inc., Publisher. New York.

Reveal, J. L. 1992. Gentle conquest. The botanical discovery of North America with illustrations from the Library of Congress. Starwood Publishing, Washington, D.C.

Spongberg, S. A. 1990. A reunion of trees. The discovery of exotic plants and their introduction into North American and European landscapes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

More about David Douglas

Douglas recognized landmarks from Vancouver’s and William Clark’s maps as soon as he sighted Cape Disappointment at the Columbia River’s fearsome bar. The collector continued to name familiar sentinels as he moved inland including “Mount Jefferson of Lewis and Clarke.”

David Douglas returned to England with many hundreds of flora and fauna specimens to process. During his stay he wrote or contributed to more than a dozen scientific papers, several of which build on the seminal first collections of Lewis and Clark.

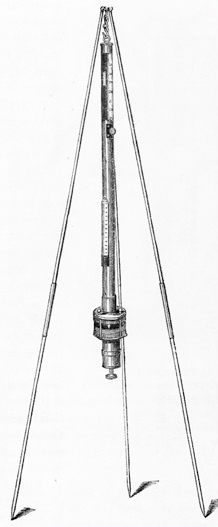

As Douglas and surveyor George Barnston set up their instruments, the pair would have been well aware that they were repeating observations taken by the Corps of Discovery in 1805 and by David Thompson in 1811.

James Reveal explains how two copies of a Douglas manuscript show he used Lewis and Clark as a reference in his descriptions of six “American Pines.”

Notes

| ↑1 | Born in 1785, William Jackson Hooker, eventually Sir William Jackson Hooker, would move from Glasgow and become director of the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew in 1841. He would build it into one of the world’s leading botanical institutions, serving there until his death in 1865. Equally comfortable with the algae, lichens, fungi, mosses and flowering plants, he published numerous works on each group of plants. He published and edited several journals as well as books of horticultural interest. He wrote floras of Scotland, the British Isles and, for our purposes, northern North America. His Flora boreali-americana, published in two volumes and twelve parts from 1829 until 1840, was mainly a vehicle for accounting for the collections of David Douglas and two other collectors of the Canadian north, Sir John Richardson (1787-1865) and Thomas Drummond (1780-1835). His son, Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1911), became the director at Kew in 1865, retiring in 1885. Joseph was Charles Darwin’s confidant and primary source of information about plants prior to Darwin’s 1859 publication of the Origin of species. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In 1793, François-André’s father, botanist André Michaux (1746-1802), offered his services to Jefferson and others in the American Philosophical Society to explore the West, and Thomas Jefferson sent him instructions similar to those Meriwether Lewis would receive in 1803. However, Michaux was also in the employ of certain French officials whose aim was to raise a western force to attack Spanish territory in America, and he got no farther west than Kentucky before the French government prudently recalled him. François-André Michaux (1770-1855), the son, carried on his father’s interest in North American plants, returning to the United States in 1801-1803 and in 1806-1807. His Histoire des arbres forestiers de l’Amerique septentrionale (3 vols., 1810-1813) became The North American Sylva (3 vols., 1817-1819) when published in Philadelphia. Nuttall redid and greatly expanded the work in 1841-1842, producing the “New Harmony edition” in which the first three volumes are a translation of the original French edition as reissued (in 1819) with an additional three volumes by Nuttall. |

| ↑3 | Pseudotsuga menzesii |

| ↑4 | David Douglas, “Observations of Two Undescribed Species of North American Mammalia,” Zoological Journal, 4 (1829), 332. |

| ↑5 | Paul H. Barrett and Alain F. Corcos, “A Letter from Alexander Humboldt to Charles Darwin.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 27 (1972):161. |

| ↑6 | Silvio Bedini, Thomas Jefferson: Statesman of Science. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1990), 490. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.