A Staple Food

Baked Camas

Camassia quamash

Attributed to Joseph Mussulman

In late September 1805, after nearly starving in the Bitterroots, the Corps of Discovery was introduced to the two staple foods of the northwest: fish and roots. All of the men immediately became seriously ill, possibly from overeating on empty stomachs. They found the root foods difficult to digest and preferred the bison they had feasted on while crossing the Great Plains, but it would be nearly a year until their return to what Lewis longingly called “the fat plains.”

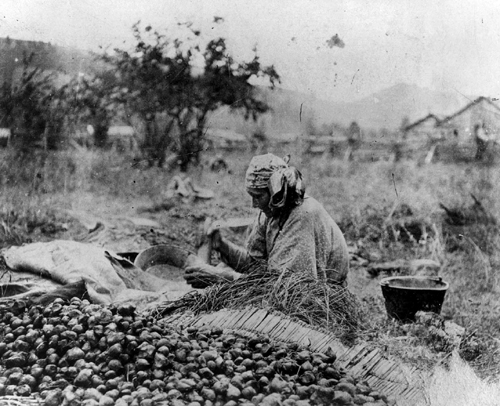

That meal of fish and roots was offered at Weippe Prairie by a group of Nez Perce Indians in the midst of their annual harvest for camas bulbs, a calorie-rich food they collected and stored for winter. Each fall Nez Perce families traveled to the large camas meadows near present-day Weippe, Moscow or Grangeville where the onion-shaped bulbs grew thickly. Women used digging tools and were able to harvest over 50 pounds (ca. 23 kilogram) a day. In a few days, enough could be gathered for a winter’s food supply. Women held rights to family camas patches, carried out the harvesting and baking, and gained the right to use surplus bulbs for trading.

At Weippe that September, Clark wrote about the abundance of camas bulbs he saw: “emence quantity of the quawmash or Pas-shi-co root gathered & in piles about the plains.” And the journals estimate that there were more than 4,500 Nez Perce. How could such large harvests of camas be sustained?

In “Camas: Sacred Food of the Nez Perce” produced by C.R. Methisen for Discover Your Northwest, Nez Perce tribal interpreters explain the significant place Camas has in their culture. View the 30-minute documentary at www.youtube.com/watch?v=esOuz0_73tg.

Cultivating and Storing Camas

Early accounts of Native American subsistence apply terms like “hunter/gatherer.” But today ethnobotonists and anthropologists describe the cultivation and storage of important food plants as complex systems capable of sustaining dependable annual supplies for large populations. The Nez Perce system for camas is a good example.

Camas harvesting requires planning because the bulbs reach maximum size and highest food value, and are best for storage, only at a specific time—after the flowers have withered. Trips to distant meadows required careful timing to meet this condition.

Intimate knowledge of detailed plant features is another element of the Nez Perce system. In the case of camas, this is especially critical, because “death camas,” a relative of edible camas, sometimes occurs in the same habitat. The two are easy to tell apart by flower color—edible camas is blue, the other creamy white.[1]Camas, Camassia quamash (kah-MASS-ee-a QUA-mash), Indian name for camas and Death camas, Zigadenus (zigg-a-DEEN-us; from Greek zygos, a yoke, and aden, a gland, referring to the paired glands); … Continue reading But since harvest occurs after flowering is over, this color cue would not be present. Perhaps trips were scheduled to the meadows during flowering to dig out the toxic species; or perhaps gatherers were able to differentiate the plants by their bulbs.

Camas bulbs were cooked to improve taste and food value. A carbohydrate in camas called inulin is difficult to digest, but after cooking for up to two days in a carefully tended pit oven, the inulin converts to fructose, which is more easily digested and tastes sweet.

Baked camas can be eaten right away. For long-term storage, though, the cooked bulbs were sun-dried, mashed, shaped into a flat loaf, and baked again.

To remain productive, camas meadows need to be open and sunny, free of encroaching tree growth. Fire was used as a tool to accomplish this. Camas bulbs themselves were tended, too. During harvest the bulbs were sorted by size: large ones were collected but smaller bulbs or bulblets were put back into the newly worked-up soil for next year.

Today’s growers of daffodils or tulips are familiar with the process of dividing and replanting bulbs. But while daffodils are grown as pretty flowers to brighten spirits, camas meadows were tended by Nez Perce women to provide sustenance for families during long rainy winters along the Clearwater River. A different relationship is implied, involving both the practice of ceremonies to mark and give thanks for this important food, and strict protocols about when to harvest and how much to take.

The descriptions of native American practices in Lewis and Clark’s journals are famous for their details and new information. But as travelers on a schedule they may have missed important elements of the Nez Perce system for producing annual crops of big camas bulbs. And, because camas cultivation was carried out “in the wild” with neither row crops nor fences, it wouldn’t have matched the explorers’ mental image of domestic food production. This was a system planned and carried out by women, whose horticultural skills were not investigated by Lewis and Clark.

Sources

Dale D. Goble and Paul W. Hirt, eds. Northwest Lands, Northwest Peoples: Readings in Environmental History. Seattle: University of Washington, 1999.

Eugene Hunn, Nch’I-Wana, The Big River: Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. Seattle: University of Washington, 1990.

Diane Mallickan, Park Ranger/Cultural Interpreter. Nez Perce National Historical Park, Spalding, Idaho. Personal interview. 11 February 2004.

Alan Marshall, Anthropologist. Lewis and Clark State College. Lewiston, Idaho. Personal interview. 20 February 2004.

Joy Mastroguiseppe, Ethnobotanist. Washington State University, Pullman, WA. Personal correspondence. 12 July 2004.

Lillian Pethtel. Kamiah, Idaho. Personal interview. 6 December 2003.

Nancy J. Turner. Plant Technology of First Peoples in British Columbia. Vancouver: Royal British Columbia Museum, 1998.

—Content reviewed by Diane Mallickan, Nez Perce National Historical Park; Lillian Pethtel, Kamiah, Idaho

Notes

| ↑1 | Camas, Camassia quamash (kah-MASS-ee-a QUA-mash), Indian name for camas and Death camas, Zigadenus (zigg-a-DEEN-us; from Greek zygos, a yoke, and aden, a gland, referring to the paired glands); elegans (ELL-a-gans; elegant). |

|---|