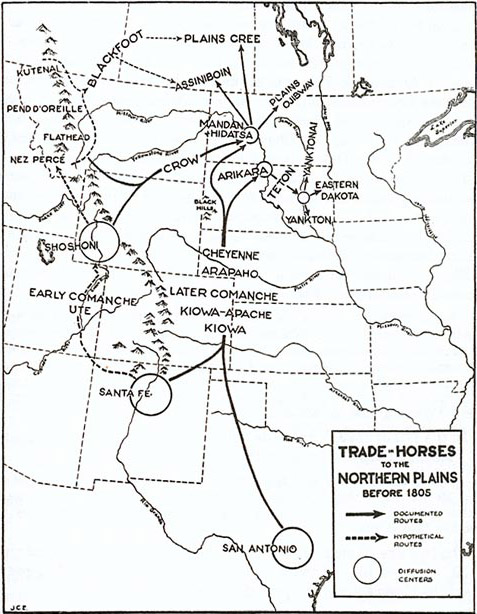

Indian Horse Acquisition, North to South

From John C. Ewers, The Horse in Blackfoot Indian Culture (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1955), Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin #159, p. 11.

Anthropologist John C. Ewers mapped the movement of horse acquisition from South to North, and tribe to tribe, over the Plains and along the Rocky Mountains. Most of the 1700s passed before horses reached the peoples of the Columbia Gorge.

One of the reasons Clark had so much difficulty in purchasing horses at The Dalles in the spring of 1806 is that he was at the very northwestern edge of their dispersal across North America. During the expedition’s first and second years, it had traveled among Plains Indian nations where horses were plentiful and had occasioned a cultural revolution. In leaving the Columbia Gorge late in 1806, however, the expedition had left horse country behind. When Clark tried to obtain horses in the Gorge the next year, he was seeking a commodity that was still relatively rare locally.

The small “dawn horse,” Hyracotherium, had gone extinct in North America[1]Formerly, the North American genus Hyracotherium was classified separately as Eohippus, from the Greek eos (dawn) and hippos (horse). Hyracotherium (here-uh-co-THEER-ee-um) is modern Latin from the … Continue reading after flourishing around 58 to 52 million years before present. Spanish explorers brought horses back to North America beginning in the 16th century, but they watched and protected their animals as closely as Lewis and Clark’s men did their guns, knives, and tomahawks. Not until horse herds were established in Spanish settlements of Mexico and the future southwestern United States did the animals begin to disperse across North America again. They were traded and raided away from Spanish towns and ranches, and further traded and raided, gradually, from tribe to tribe. Initial-contact accounts from white explorers and traders provide information on which tribes owned horses—and which still did not—when whites first visited them. Horses’ dispersal north on the Great Plains, west of the Rocky Mountains, and east toward the Mississippi, can be dated, in part, from those accounts. Oral traditions from tribes who received horses later add further dating information.

The route for horses to Indians of The Dalles was from the Santa Fe area through the Utes and Comanches of Utah (beginning in 1705), to the Comanches’ relatives, the Shoshonis of Wyoming (roughly the 1710s to 1720s), to the Nez Perce (around 1730) who recalled the Shoshonis as their source. Living in a land blessed with grasses and remote from raiders from other nations, the Nez Perces developed horse herds and practiced controlled breeding. With animals to spare in trade, they began to take horses to The Dalles’ trading mart late in the 18th century, initiating the horse’s distribution onto the Columbia Plateau.

The Nez Perce and their neighbors the Palouse Indians also developed the Appaloosa breed, distinguished by its spotted or partially spotted coat (which can be of any color). These are light but sturdy steeds standing 57″ to 64″ tall. Their name comes from the Palouse River of Idaho and Washington, but to many Indians they were “raindrop horses,” for their markings.

During the Indian Wars on the Northern Plains (including the Nez Perce War of 1877, when the army trailed Nez Perces from Idaho almost to Canada for months), U.S. Army horses required forage carried in supply wagons, and had difficulty crossing some rivers. To cavalry commanders’ frustration, the smaller and sturdier Plains Indian horses (which they distinguished as “ponies”) ate natural grasses and more easily forded and swam rivers. In short, army animals—unlike those that were Indian-owned—had had some ability to live off the land bred out of them.

Primary Source

John C. Ewers, The Horse in Blackfoot Indian Culture (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1955), Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin #159.

Notes

| ↑1 | Formerly, the North American genus Hyracotherium was classified separately as Eohippus, from the Greek eos (dawn) and hippos (horse). Hyracotherium (here-uh-co-THEER-ee-um) is modern Latin from the Greek hyrax (here-ucks) for a small herbivore, and therion (THEER-ee-on) for wild animal. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.