Chuck-will’s-widow

Antrostomus carolinensis (Caprimulgus c.)

Birds of America, Plate 52. This image is in the public domain.

On 4 June 1804, Clark and John Ordway reported that “Nightingale” has sung all of the previous night. Here is the text from Clark’s field notes:

passed a Creek on Lbd Side 15 yd. wide, I call Nightingale Creek. this Bird Sang all last night and is the first of the kind I ever herd, below this Creek and the last

The Codex “A” version, Clark’s notebook, differs slightly:

passed a Small Creek at 1 ms. [Nicholas Biddle: 1 mile] 15 yd. Wide which we named Nightingale Creek from a Bird of that discription which Sang for us all last night, and is the first of the Kind I ever heard.

Ordway also mentioned the incident:

passed a Creek on the South Side about 15 yds wide which we name nightingale Creek, this Bird Sung all last night & is the first we heard below on the River we passed

Prior Analysis

What bird sang that night? It is worthwhile to repeat Elliott Coues’s answer to this question because part of it has been forgotten in subsequent discussions: “No species of Nightingale (Daulias luscinia) in any proper sense of the word, is found in North America. The so-called “Virginia nightingale” is the Cardinal redbird (Cardinalis virginianus).”[2]Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (New York: Dover Publications, n.d.), 1:14

Thwaites cites Coues, then adds a remark attributed to James N. Baskett: “The ordinary mockingbird sings in the night; so also, occasionally, do the catbird and the brown thrasher.”[3]Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition 1804-06 (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1904-05), 1:39. I quote here from the reprint edition (The Antiquarian Press, 1959).

Elijah Criswell, in his Lewis and Clark: Linguistic Pioneers, downplays the idea of both the mockingbird (mock-thrush) and cardinal because “one would have thought that Clark knew both birds well.”[4]Elizah Criswell, Lewis and Clark: Linguistic Pioneers (Columbia: University of Missouri Studies, Vol. 15, 1940), 59.

Raymond Burroughs, in his Natural History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, does not even list “nightingale” in the index, only the “Eastern” cardinal: “In this instance Clark called the bird a nightingale.”[5]Raymond D. Burroughs, The Natural History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1961), 257-58.

In Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Naturalists, Paul Cutright adds nothing more, then dismisses the idea of the cardinal and concludes: “The bird in question is a mystery.”[6]Paul Russell Cutright, Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Naturalists (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, Bison Books, 1989), 55.

Virginia Holmgren, advances the idea of the hermit thrush.[7]Virginia C. Holmgren, “Birds of the Lewis and Clark Journals,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 10, Nos. 2 and 3, May 1984. See on this site Birdwatcher’s Guide to Lewis and Clark. It is true that this bird has an especially lovely song and is sometimes referred to as a nightingale.[8]John K. Terres, ed., The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds (New York: National Audubon Society, 1980), 632. The veery (a thrush) is also mentioned as a “nightingale.”

Moulton adds a suggestion from Paul Johnsgard, the whip-poor-will, but then points out that the journals later refer to this bird by name.[9]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986-99, 12 volumes), 2:276.

We have here six possible answers to the question, What bird sang that night? Which of the six is correct? Or are we dealing with another bird altogether? Here are the candidates, along with this author’s objections to each:

Possible Candidates

Northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). It is inconceivable that either Lewis or Clark could have traveled in central Missouri in May and early June without hearing and seeing the cardinal dozens, if not hundreds, of times. It is one of the most common and most notable singers in the spring. Furthermore, on 10 June 1806, Lewis described the western tanager as “about the size of the Virginia Nightingale” (a common name for the northern cardinal in the early 19th century).[10]Ibid., 7:340. Certainly the captains knew the cardinal well.

Northern mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos). Same objection. The mockingbird is mentioned by name elsewhere in the journals although sometimes lumped with the brown thrasher (brown thrush). Central Missouri birdwatchers know that the mockingbird often sings at night, especially if the moon is full. When asking a Missouri state ornithologist, he said almost any bird will sing at night if the moon is full. But the moon was in the last quarter that June night of 1804, just four nights from the new moon.[11]U.S. Naval Observatory.

Gray catbird (Dumetella carolinensis). On 6 June 1805, Lewis described the shrike as “about the size of the blue thrush or catbird.” Again, same objection. The catbird is common in central Missouri and the explorers could have heard it many times before that night.

Brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum). Same objection.

Hermit thrush (Catharus guttatus). No ornitholigist the auther knows has ever heard this bird sing in central Missouri. People see it regularly during the fall migration, and if the winter is mild a few thrushes will stay around. The spring migration brings many back to this area, but they are long gone by June, in their breeding grounds much farther north. The latest recorded sighting for this species in Missouri in the spring is May 7. I cannot imagine the hermit thrush being the bird the expedition heard that night.

Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus, previously Caprimulgus vociferus). While it is a famous nightsinger, both Lewis and Clark mention it elsewhere in the journals, and the men could have heard it many, many times before. For those reasons, almost everyone disregards this choice.

The Chuck-will’s-widow

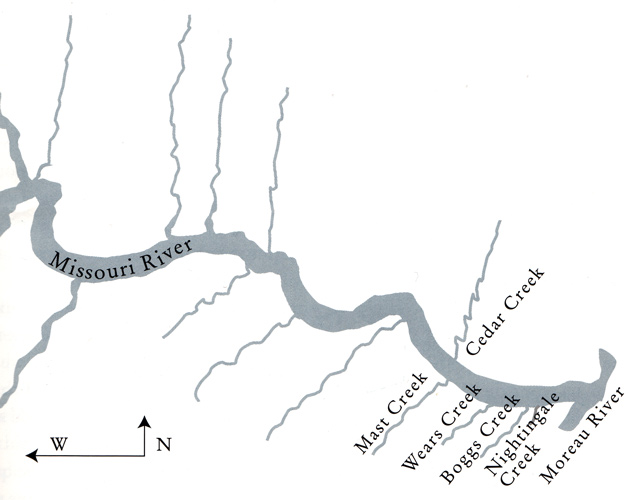

William Least Heat-Moon offered to this author his theory about the bird in question. The idea had come to him, he said, one night about a month earlier, when he was working on his new book.[12]William Least Heat-Moon, River Horse (New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1999). His house is near the Missouri River, and he spoke of hearing the incessant call of a chuck-will’s-widow (Antrostomus carolinensis, previously Caprimulgus c.) coming from the very direction of the Moreau River. He had heard a chuck-will calling from that direction—and only that direction—every June for the last 14 years.

In June 1999, another possible piece of the puzzle turned up. William Least Heat-Moon was reading Charles William Janson’s A Stranger in America and found this passage, first published in 1807:

A traveller has confounded the mockingbird with the Virginia nightingale, and speaks of them as the same bird by different names; but they are very different, both in colour and song, The redbird of Virginia and the Carolinas, is by the English called the Virginia nightingale, a name not given by Americans to any bird of the woods . . . . If the name nightingale were to be given to any of the feathered race in the southern states, that called the “Whip-poor-will,” is best entitled to it. This bird sings a plaintive note almost the whole night long, resembling the pronunciation of the words by which it is named.[13]Charles William Janson, A Stranger in America 1793-1806 (London, 1807). I quote here from the reprint edition (New York: The Press of the Pioneers, Inc., 1935), 355.

Janson’s commentary is as close to the time of the singing of Clark’s bird as one could expect. It is clear that the writer, an Englishman, knew the nightingale, and yet he did not hesitate to use the word for the whip-poor-will—a bird that sings at night. But as Coues, and ornithologist, noted, “No species of Nightingale (Daulias luscinia) in any proper sense of the word is found in North America.” Perhaps a “nightingale” is simply any bird that sings at night.

In central Missouri we have two birds that easily fit this requirement, especially in the spring. One is common throughout the state—the whip-poor-will. The other, less common—the chuck-will’s-widow—just about reaches its northern limit in central Missouri, and it fits all the requisites to become the nightsinger of 3 June 1804.

The mystery bird captured the attention of the expedition because of its song, its call, its noise in the night. Whip-poor-wills and chuck-wills are both nightjars, so called because of their penetrating, repetitious calls. The bird the expedition heard must have jarred the night. It could well have been a chuck-will’s-widow.

Notes

| ↑1 | James Wallace, “The Mystery of Clark’s Nightingale”, We Proceeded On, May 2000, Volume 26, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article with an analysis of the location of Nightingale Creek and interactions with William Least Heat-Moon is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol26no2.pdf#page=20. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (New York: Dover Publications, n.d.), 1:14 |

| ↑3 | Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition 1804-06 (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1904-05), 1:39. I quote here from the reprint edition (The Antiquarian Press, 1959). |

| ↑4 | Elizah Criswell, Lewis and Clark: Linguistic Pioneers (Columbia: University of Missouri Studies, Vol. 15, 1940), 59. |

| ↑5 | Raymond D. Burroughs, The Natural History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1961), 257-58. |

| ↑6 | Paul Russell Cutright, Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Naturalists (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, Bison Books, 1989), 55. |

| ↑7 | Virginia C. Holmgren, “Birds of the Lewis and Clark Journals,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 10, Nos. 2 and 3, May 1984. See on this site Birdwatcher’s Guide to Lewis and Clark. |

| ↑8 | John K. Terres, ed., The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds (New York: National Audubon Society, 1980), 632. The veery (a thrush) is also mentioned as a “nightingale.” |

| ↑9 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986-99, 12 volumes), 2:276. |

| ↑10 | Ibid., 7:340. |

| ↑11 | U.S. Naval Observatory. |

| ↑12 | William Least Heat-Moon, River Horse (New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1999). |

| ↑13 | Charles William Janson, A Stranger in America 1793-1806 (London, 1807). I quote here from the reprint edition (New York: The Press of the Pioneers, Inc., 1935), 355. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.