Sowing the Seed

This third-grade medal, minted during Washington’s second administration, depicts the importance of farming in America. it was one of the medallions carried by Lewis and Clark and given to the lesser chiefs of the various Indian tribes. For more, see Peace Medals.

“I wish the to request a meeting,” wrote Isaac Briggs, a politely persistent Quaker, to Secretary of State James Madison on the first day of the new year 1803. Briggs asked Madison to convene the meeting “in the Representatives chamber, or some other convenient apartment, of those members of both houses of Congress who have zeal for the improvement of American Agriculture . . .”

So it was on 25 February 1803, the National Intelligencer in Washington reported “a number of respectable and patriotic citizens” had met three days earlier at the unfinished Capitol building to organize something called the American Board of Agriculture.

The newspaper listed 45 members, ostensibly a private group not part of the Federal government. It was an odd bunch of soft-handed political celebrities including three future U.S. Presidents and three drafters of the Constitution. Madison was the Board’s president, and instigator Briggs was secretary. A “Committee of Correspondence” was made up generally of one Senator and one Representative from each state, plus two territorial governors.

But the name that really leaps off the page is that of Meriwether Lewis, representing the “Territory of Columbia.”

True, Lewis was a qualified resident of that Federal district, living with President Thomas Jefferson in a big mansion on Pennsylvania Avenue. But as the President’s private secretary, the 28-year-old Army captain wasn’t in the same league with the political heavy-weights on the new board, and his mind right then certainly wasn’t on scientific tillage. On the very same day as Madison’s meeting, Congress voted final approval of the $2,500 appropriation needed to launch Lewis’s Western expedition. Just 21 days later the District of Columbia’s agriculture correspondent quietly left town for a three-month shopping trip to Harpers Ferry and Philadelphia—his first step to eventual glory on the shores of the Pacific.

Political Germination

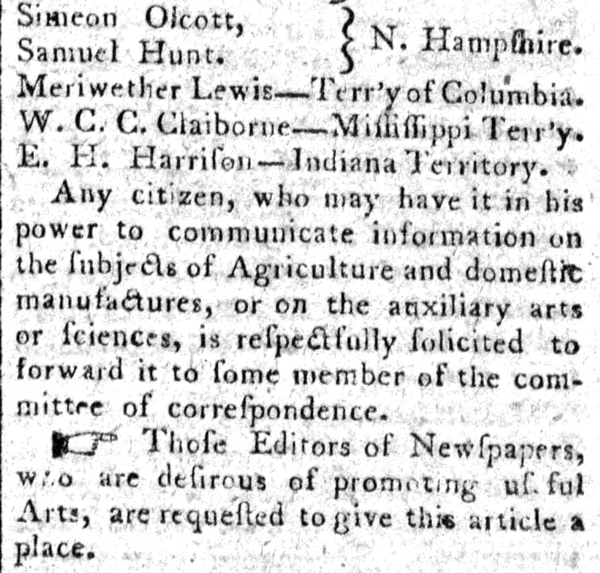

The last part of the above National Intelligencer, 25 February 1803, article reads:

Meriwether Lewis—Terr’y of Columbia.

W. C. C. Claiborne—Mississippi Terr’y.

E. H. Harrison—Indiana Territory.

Any citizen who may have it in his power to communicate information on the subjects of Agriculture and domestic manufactures, or on the auxiliary arts or sciences, is respectfully solicited to forward it to some member of the committee of correspondence.

Those Editors of Newspapers, who are desirous of promoting useful Arts, are requested to give this article a place.

Despite the do-good hopes of its distinguished sponsors, the American Board of Agriculture never amounted to much. The curious story of Lewis’s phantom membership is noteworthy mainly for the light it throws on his two-year, pre-expedition job as Jefferson’s secretary. Today the White House staff numbers in the hundreds; in 1803, the staff was Lewis alone. He had to be a utility player of varied talents and interests, especially in working for a boss who liked to dabble in everything.

As owner of a working plantation and inventor of a new plow, Jefferson envied the British Board of Agriculture, which served as a national clearinghouse for innovations in seed varieties, fertilizers, and livestock management. At dinner one evening in March 1802, the President leaned toward Representative Samuel Latham Mitchill of New York with a suggestion for emulating the British farm board. According to Mitchill, Jefferson said it would be “highly desirable” if all existing state agricultural societies could have representation at the national level; “this he conceived might be done without expense by appointing one or more of the members of Congress to this general society.”

So the President himself was one of the farm board’s early ringleaders. The idea appealed to Mitchill, who admired Jefferson as a fellow Renaissance man. An Edinburgh-schooled physician, Mitchill was an expert on the chemistry of soils and practically everything else: meteors, steamboats, minerals, fish, Indians, Western American geography. The New Yorker’s reputation as a ready talker on any subject sometimes drew ridicule: “Tap the Doctor at any time, and he will flow.” Mitchill knew Lewis from Jefferson’s dinner parties, and held him in awe after the Expedition’s return. “They achieved so much,” said Mitchill, “that I told Lewis one day shortly after his return to Washington, when he dined with me, I looked upon him almost as a man arrived from another planet.”

In early 1803, Mitchill began rounding up his fellow legislators to serve on the new farm board. Meanwhile, Isaac Briggs, a Maryland farmer and surveyor, was booming the same idea to Madison. Now that Princeton-educated, much-absent owner of a 1,200-acre Virginia plantation might have seemed only nominally a son of the soil, more a cultivator of Constitutions than cotton. But in fact Madison and Briggs were both members of the Farmers’ Society of Sandy Springs, Maryland, and in 1817 (after his own turn in the White House) Madison became president of his neighborhood Albemarle Agricultural Society. Perhaps extravagantly, Jefferson called his Secretary of State “the best farmer in the world.”

Madison then, agreed to preside at the 22 February 1803, organizing meeting at the Capitol. Representative Mitchill was one of the vice presidents; Senator George Logan of Pennsylvania, an author of pamphlets on scientific farming, was the other. The treasurer was Joseph Nourse, a Treasury Department bureaucrat.

Bi-partisan Fertilization

Politically, the officers were all good Jeffersonians. Was the American Board of Agriculture just a Republican party front to promote an ideology of agrarianism? Some may have hoped so, but it should be remembered the most American voters of that day were farmers, and not even the declining Federalists could ignore them. Among the 10-or-so Federalists listed on the Committee of Correspondence were two Senators who had been with Madison during that steamy 1787 summer of Constitution-writing in Philadelphia: Abraham Baldwin of Georgia, and Jonathan Dayton of New jersey, the youngest signer.

But perhaps the most prominent Federalist token of bipartisanship was John Quincy Adams, the ex-president’s son, freshly elected to the U.S. Senate by the Massachusetts legislature. Like many gentlemen-farmer members of the new board, this future President was more gentleman than farmer. During one Congressional recess Adams went home to attempt “agricultural pursuits,” but confessed to his diary: “I soon found they lost their relish, and that they never would repay the labor they require.” Nor was there much dirt under the fingernails of William Henry Harrison, governor of Indiana Territory and something of a full-time officeholder until his death in the White House in 1841. (The National Intelligencer evidently botched Harrison’s initials, rendering them “E.” H.)

Was Meriwether Lewis a Plant?

And what of Meriwether Lewis, soldier? In his late teens Lewis had capably managed the family farms for a couple of years, but “yielding to the ardour of youth” (as Jefferson put it) at age 20 he forever chucked farm chores for a more exciting life in the Virginia militia. as an explorer of the West, he did not reveal a plowman’s mind. Of course, Lewis gave his tobacco-growing chief a detailed description of Arikara methods of cultivating and curing tobacco. He observantly reported the broad plains of northeastern Montana consisted of “a dark rich mellow looking lome,” but leaped to no eager speculation about what kind of crops it might grow. In line with government policy of the time, he visualized a trans-Mississippi landscape dotted with Indian trading posts, not wheatfields.

In his known writings Lewis never explained his glancing contact with the American Board of Agriculture, but there can be little doubt he was doing Jefferson’s bidding as a conspicuous Presidential stand-in. Lewis was well known in the small government town of Washington as a subordinate host at Jefferson’s dinners and a carrier of Jefferson’s messages to the chambers of Congress. (To this day, House and Senate floor proceedings are interrupted when a White House messenger enters, bows ceremonially to the presiding officer and hands over his package.) So when Lewis’s name appeared in a loyal Republican newspaper as one of the farm board’s organizers, it was an easy-to-read signal that the board had the President’s blessing and protection. Lewis’s usefulness to the project essentially ended with that newspaper listing, and he was then free to turn to his great mission Westward.

Going to Seed

And the new Board itself soon vanished from history’s view. Its main ramrod was Secretary Briggs, who outlined initial plans in an “Address” published in the National Intelligencer on 2 March 1803. Briggs invited Americans everywhere to send to the new clearinghouse information about local improvements in farm machinery, seeds, fences, livestock breeds and fertilizer. The board then would publish ideas deemed worthy of national circulation. At the first meeting it was agreed that the board would next convene “near the commencement of the ensuing session of Congress, when a general election will take place.” That would be some time the following autumn.

Sad to say, the board proved vulnerable to the problems of any letterhead group whose celebrity-members merely lend their names to a good cause. Jefferson himself soon contributed to the board’s unraveling by appointing ramrod Briggs to a distant job as Federal “Surveyor of the land south of Tennessee.” In a June 30 letter to Sir John Sinclair, founder of the British Board of agriculture, Jefferson said Madison’s group “was formed the last winter only, so that it will be some time before they get under way.” Perhaps he had the Briggs vacancy in mind as well. On his way to Natchez, incidentally, surveyor Briggs conferred on 10 May 1803 in Philadelphia with Lewis, his fellow farm board truant, on techniques of celestial navigation.

The first session of the new 8th Congress assembled on 17 October 1803, but from then until adjournment on 27 March 1804, there wasn’t a whisper about the board’s promised second meeting either in the National Intelligencer or the Philadelphia Aurora, its biggest outside cheerleaders. Standard reference works on early American farm societies, such as the Agriculture Department’s 1929 survey, A History of Agricultural Education in the United States, 1785-1925, do not mention the board at all. The board apparently published no findings, and left no institutional descendants. The government itself continued to resist a major plunge into farming until Congress established the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1862.

Notes

| ↑1 | Arlen J. Large, “The Phantom Farmer: Lewis and the American Board of Agriculture,” We Proceeded On, May 1989, Volume 15, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The editor here has made minor changes to work as a web page. The original is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol15no2.pdf#page=16. |

|---|