Of Special Interest

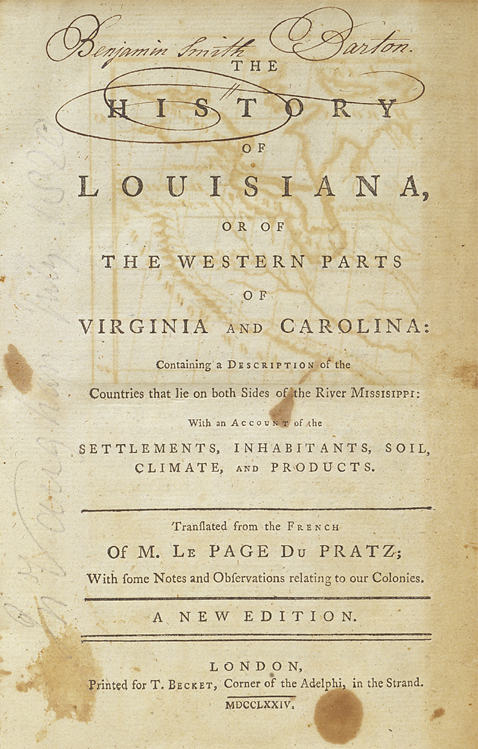

The title page to the one-volume English edition of 1774 that Benjamin Smith Barton loaned to Meriwether Lewis to take along on the Expedition of 1804-06.

What was it about the History of Louisiana that so interested Lewis? The 1774 edition was divided into four books, published in one volume. The first book gave a history of the exploration and colonization of Louisiana. In Book Two, du Pratz described Louisiana, “the Country and its Products.” He discussed the many rivers that empty into the Mississippi; the lower Mississippi region and its highlands, with descriptions of the soil, vegetation, wildlife, and minerals; the Missouri River; the Mississippi’s agricultural products and their cultivation, and other natural resources (timber, fur, minerals, etc.). Du Pratz admitted that the land north of the Missouri was Terra Incognita. Book Three was devoted to the natural history of Louisiana, in which he described the various crops that were grown, the plants from fruit trees to creeping plants, quadrupeds (including the buffalo), birds and insects, and fish and shellfish. Book Four discussed the origins of the Native Americans. Du Pratz listed the tribes that lived along the Mississippi and described their languages, customs, occupations, and ceremonies, with special attention given to the Natchez.

In his instructions to Lewis, Jefferson stated that the mission of the expedition was to explore the Missouri River and any other river that might offer a direct and practicable water route across the continent. Along the way, the members of the expedition should note the soil and face of the country, its vegetables, animals, minerals, and climate. They should also become acquainted with the Indian nations along the route, their numbers, territory, language, customs, occupations, etc.[1]Jefferson Instructions to Lewis, [20 June 1803], Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962), 61-62. In other words, du Pratz’s work could serve as a paradigm for the kind of information Jefferson wanted the expedition to acquire. What du Pratz had done for the Mississippi River valley Jefferson wanted Lewis to do for the Missouri River system.

Antoine du Pratz

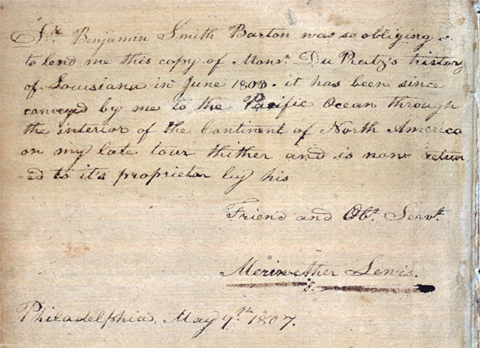

Transcript:

Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton was so obliging as to lend me this copy of Monsr. Du Pratz’s history of Louisiana in June 1803. It has been since conveyed by me to the Pacific ocean through the interior of the Continent of North America on my late tour thither and is now returned to it’s proprietor by his

Friend and Obt. Servt.

Meriwether LewisPhiladelphia, May 9th, 1807

Little is known about Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz (1695?-1775) beyond the meager personal revelations in his Histoire de la Louisiane.[2]Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz, Histoire de la Louisiane, 3 vols (Paris: De Bure, 1758). He was born either in the Netherlands or France and was raised in the latter country. He graduated from a French cours de mathematiques and considered himself an engineer and professional architect. Serving with Louis XIV’s dragoons in the French Army, he saw service in Germany in 1713 during the War of the Spanish Succession. On 25 May 1718 he left La Rochelle, France, with 800 men on one of three ships commissioned by the Company of the West (known also as the Mississippi Company) bound for Louisiana. Du Pratz arrived in Louisiana three months later on 25 August 1718. At that time the colony’s French population was very small and included secular and religious officials; a limited number of concessionaires, who received large land grants; a larger number of habitants, a group that included migrants sent by non-emigrating concessionaires to work their lands; and those who obtained smaller land grants of their own.[3]Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz, History of Louisiana, edited with an introduction by Joseph G. Tregle, Jr. (London: T. Becket, 1774; reprint, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1975), xx; … Continue reading It appears that du Pratz was one of the last group. All were supplemented by a far more transient population of traders, soldiers, and indentured servants.

Du Pratz spent four months at Dauphin Island before he made his way to Bayou St. John, where he established his grant and set up a plantation using indentured labor. The young settler was only about twenty-three at the time. After living on the banks of Bayou St. John for about a year, he left for the more promising area of the Natchez Indians, below the bluffs of the Mississippi, upon which the French Fort Rosalie had been constructed in 1716 (present-day Natchez, Mississippi). The climate there was more healthful and the soil richer and ideally suited for growing tobacco. Du Pratz took with him two African slaves, a man and his wife, and a young Chitimacha woman purchased in New Orleans. Upon his arrival he bought land from the Natchez Indians and began to grow tobacco. He also acquired two parcels of land on behalf of the commissary of the colony, Marc-Antoine Hubert, one for personal use and one for the Company.[4]Du Pratz, History of Louisiana (1947), 20-24; Patricia Galloway, “Rhetoric of Difference: Le Page du Pratz on African Slave Management in Eighteenth-Century Louisiana,” paper presented at … Continue reading

For eight years du Pratz dwelled among the Natchez Indians, observed their customs, and became their friend. With the Natchez as guides and companions, he traveled long distances through the surrounding countryside, from whence sprang his lengthy observations on the local flora and fauna. However, during this period French relations with the Natchez were deteriorating and in 1728 du Pratz accepted an offer from the Company to manage its plantation across the river from present-day New Orleans. This, the largest establishment in the colony, employed more than two hundred Africans, directly owned by the Company, in producing tobacco and cotton. Du Pratz also apparently supervised Africans imported by the Company before they were sold at auction, as the Company made temporary use of them for the manifold tasks of maintaining the city and its harbor.[5]Daniel Usner, “From African Captivity to American Slavery: The Introduction of Black Laborers to Colonial Louisiana,” Louisiana History 20 (1979): 25-48, cited in Galloway, … Continue reading

In 1729, the Natchez Indians massacred the French at Fort Rosalie. The subsequent retaliation by the French and their Choctaw Indian allies wiped out the Natchez as a nation. As a result of the massacre and other losses it had sustained, the Company of the West surrendered its charter to the crown and Louisiana became a royal province of Louis XV. Du Pratz retained his position as director of the plantation, now become the King’s in 1730. In 1734, there was a change of governor of Louisiana, the plantation was “put on a new footing,” and du Pratz’s position was abolished. At this point, he decided to return to France, arriving in La Rochelle on 25 June 1734. In all du Pratz had spent sixteen years in Louisiana.[6]Tregle, introduction to History of Louisiana (1975), xxiii; du Pratz, History of Louisiana (1947), 85, 186-7.

It is not known what the former colonial planter did between the time of his arrival back in France and the publication of his first Louisiana article in 1751. He apparently associated with a literary circle, for he claims it was his “learned friends” who persuaded him to begin writing his memoirs. These first appeared in a series of twelve installments in the Journal Oeconomique between 1751 and 1753.[7]Shannon Lee Dawdy, “Enlightenment from the Ground: Le Page Du Pratz’s Histoire de la Louisiane,” French Colonial History 3 (2003): 18.

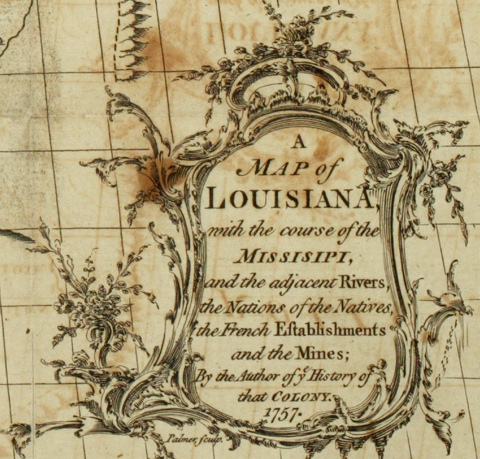

Louisiana in 1757

This cartouche carries the date 1757 because the map was originally engraved in French for the first edition (three volumes, Paris, 1758). When the work was translated into English for publication in London in 1763 (two volumes) and 1774 (one volume), the map was re-engraved in English but retained the earlier date.

Prior to this, the most recently published history of Louisiana was Histoire et description générale de la Nouvelle France (Paris, 1744) by the Jesuit Pierre de Charlevoix, who visited the region in the 1720s. In 1753, the Abbé de Mascrier published a two-volume work under the title Mémoires historiques sur la Louisian composés sur les mémoires de M. Dumont par M.L.L.M, which appeared at the same time as du Pratz’s final Journal article.[8]Abbé de Mascrier, Mémoires historiques sur la Louisiane composés sur les mémoires de M. Dumont par M.L.L.M, 2 vols. (Paris: Buache, 1753). M. Dumont was another young soldier who had sought his fortune in Louisiana and eventually returned to France. Mascrier’s history was based upon manuscripts that Dumont had written about his experiences in Louisiana, but Mascrier rather extensively and imaginatively edited the manuscript before publication. Du Pratz and Dumont knew one another in the colony (Dumont’s stay from 1719 to 1737 nearly coincided with that of du Pratz), and thought of one another as friends until the Dumont/Mascrier work accused du Pratz of gross inaccuracies in his competing series of historical articles. This insult, as well as the encouragement of his friends, seems to have spurred du Pratz to expand his journal articles into his treatise Histoire de la Louisiane, published in 1758, forty years after the author landed in New Orleans.[9]Dawdy, “Enlightenment from the Ground,” 19; Tregle, introduction to History of Louisiana (1975), xxvi.

The full title of this work was Histoire de la Louisiane, contenant la découverte de ce vaste pays; sa description géographique; un voyage dans les terres; l’histoire naturelle, les moeurs, coutumes & religion des naturels, avec leurs origines; deux voyages dans le nord du nouveau Mexique, dont un jusqu’‡ la Mer du Sud; ornée de deux cartes & 40 planches en taille douce,[10]History of Louisiana, including the discovery of that vast land; its geographical description; a voyage through the territory; the natural history, the customs, dress & religion of the natives, … Continue reading and it first appeared in three volumes. His work covered French colonial activities, explorations, and military campaigns; Louisiana’s natural history and economic potential; and descriptions of the customs and conditions of Native Americans in the region, particularly of the Natchez. What he wrote about the Natchez–their lives, customs, religious ceremonies, and social structure–is considered the best and most accurate account of these indigenous inhabitants of Louisiana, who had been annihilated by the time du Pratz returned to France. He has also recorded much information on the other Indian tribes of the lower Mississippi River country. Regarding the region’s economic potential, du Pratz was optimistic about prospects for economic development of the colony and provided detailed descriptions and recommendations for tobacco and indigo cultivation, as well as silk and tar production. His work was a practical handbook for those willing to establish themselves along the Mississippi.[11]Dawdy, “Enlightenment from the Ground,” 19-20; Arthur, foreword to History of Louisiana (1947).

In 1763, the three-volume first edition in French was followed by a two-volume edition in English, and eleven years later, in 1774, by a one-volume edition in English, entitled The History of Louisiana, or of the Western Parts of Virginia and Carolina.[12]Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz, History of Louisiana, or of the Western Parts of Virginia and Carolina; Containing a Description of the Countries that lye on both Sides of the River Missisippi: With … Continue reading The texts of both English editions were identical, and they both lacked the original French edition’s many illustrations and much of its text, as the English publisher said he had eliminated du Pratz’s digressions and reordered the chapters. The London editions did have two folding maps, one of the Louisiana province, the other of the country about the mouths of the Mississippi River. Thomas Jefferson possessed copies of Charlevoix and Dumont and the 1763 edition of du Pratz in his private library. Meriwether Lewis toted a copy of the 1774 edition of du Pratz, which he had borrowed from Benjamin Smith Barton, on his expedition through the northern reaches of the Louisiana territory.[13]Dawdy, “Enlightenment from the Ground,” 30; Arthur, foreword to History of Louisiana (1947); Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, compiled with annotations by E. Millicent … Continue reading

First Explorations

The full dimensions of this map as it appeared in the 1763 and 1774 editions are 11-7/16 inches high by 13-5/8 inches wide. The scale is 1:8,500,000.

—Joseph Mussulman

Some years before Jefferson was elected President, this part of Louisiana had become a focus of intense political concern, especially regarding the location of the boundary between Spanish and U.S. territory, and the route to Santa Fe. Jefferson sent two separate exploratory expeditions into this arena while Lewis and Clark were still en route through the Northwest. One, led by Jefferson’s American Philosophical Society colleague, William Dunbar, made a short trip up the Ouachita River–du Pratz’s Black River–in 1804 (See Hunter and Dunbar Expedition). The other was the ill-fated Freeman-Custis Expedition up the Red River in the spring and summer of 1806.

William Clark was familiar with the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers well before he joined Lewis on the Expedition to the Pacific. In 1795 he commanded a barge”–perhaps similar to the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) Lewis ordered built for his exploration of upper Louisiana–with a company of seventeen soldiers on a diplomatic mission to the Spanish authorities at Chickasaw Bluffs, and three years later he piloted a flatboat-load of tobacco from the Clark plantation at the Falls of the Ohio, down to New Orleans.

—Joseph Mussulman

Du Pratz’s work contained information of particular interest to the Corps of Discovery, namely, the first published account of Etienne Venyard Sieur de Bourgmont’s expedition to the Paducah Indians in 1724.[14]Du Pratz, History of Louisiana (1947), 59-69. This narrative was extracted and abridged from Bourgmont’s journal, which described a mission to conciliate peace between the Paducahs and several neighboring tribes, the latter allies of the French. Starting out from Fort Orleans on the north bank of the Missouri River (present-day Kansas City, Missouri), where he was commandant, Bourgmont journeyed westward to the village of the Kansa Indians (near present-day Doniphan, Kansas). He continued his journey further west to the Paducahs, who were in an encampment on the prairies east of the Big Bend of the Arkansas. Scholars are divided as to whether they were Comanche or Plains Apache who had traveled east of their normal hunting grounds. They gave a warm reception to Bourgmont. When Bourgmont returned to Fort Orleans, he had traversed the future state of Kansas end to end—from the Missouri to the plains bordering the front range of the Rocky Mountains. He noted the streams, the boundless prairies, the millions of buffalo. On his map, du Pratz showed the country of the Paducahs extending from the headwaters of the Republican River to south of the Arkansas, the great village of the tribe being located near the source of the Smoky Hill River. “Lewis and Clark would have access to far better information once they reached St. Louis, but at the earliest stages of their journey, Bourgmont’s account as given in du Pratz added one more piece to their understanding of the Missouri River.”[15]William H. Goetzmann and Glyndwr Williams, The Atlas of North American Exploration (New York: Prentice Hall, 1992), 95; James P. Ronda, introduction to Gilman, Lewis and Clark, 23; Frank W. Blackmar, … Continue reading

Du Pratz also described the journey, as recounted to him, of the Indian Moncacht-Apé, who presumably traveled to the Pacific Ocean via the Mississippi, Missouri, and Columbia rivers. After moving a great distance along the Missouri River, he headed northward on land until he reached the Beautiful River, which runs westward in a direction contrary to that of the Missouri. After traveling nearly a month along this river, he finally arrived at an Indian nation that was only one day’s journey from the Pacific Ocean. These Indians told him of white men with beards who from time to time arrived in “floating villages.” He traveled further with these Indians and actually participated in an attack on the whites who landed on the coast. The journey of Moncacht-Apé, as reported by du Pratz, was an early record of an overland trip to the West.[16]Du Pratz, History of Louisiana (1947), 285-90. This same story appears in Dumont’s Memoires, and it is unknown who plagiarized whom. Significantly, this account makes no mention of the Rocky Mountains.

Geographical Information

Special mention must be made of du Pratz’s map of Louisiana province. The early French explorers were responsible for two geographical theories that played an important role in cartographical representations of western North America, including du Pratz’s. The pyramidal height-of-land theory postulated that America’s great rivers all originated from one mythical spot in the mountains before they flowed eastward to outlets in the Mississippi River, northward to Hudson Bay, or westward to the Pacific Ocean. The sources of the rivers were thought to be so close together that there was only a short portage between them.

The second geographical theory, known as symmetrical geography, held that the topography of the western half of the continent was a mirror image of the continent’s eastern landforms and waterways. Thus the drainage patterns of the rivers on the Pacific slopes of the western mountains would resemble those of the rivers on the eastern side of the Appalachian Mountains.[17]www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/lewis_clark/easy_comm.html; Gilman, Lewis and Clark, 56.

A corollary to these two theories was the Long River theory that postulated that there was a system of interlocking lakes and rivers that formed a water route to the West Coast. Later this system was replaced by a rumored pair of rivers, one running east and the other west, connecting near their sources. The westward-flowing river provided a direct route to the Pacific Ocean. This concept had the benefit of some basis in reality, in the Columbia River. The first apparent documentation of this river was the account of Louis Armand de Lom d’Arce, Baron de Lahontan. His book, Nouveaux voyage de M. le baron de Lahontan, dans l’Amérique Septentrionale (The Hague, 1703), was an account of an expedition he said he had made down a mysterious, westward-flowing river that was a tributary of the Upper Mississippi. This he called the Rivière Longue, or Long River, and he illustrated it in considerable detail, suggesting it as a passage to the Pacific Ocean.[18]www.finebooksmagazine.com/issue/0301/river.phtml

Du Pratz’s map of Louisiana province depicts the lower Mississippi and lower Missouri rivers fairly accurately but it mistakenly shows the Missouri River flowing eastward, as reported in Moncacht-Apé’s tale. This representation was consistent with the widely held pyramidal height-of-land theory. Du Pratz estimated the length of the lower Missouri to be nearly 2,400 miles; the actual distance from the mouth of the Missouri to the Three Forks of the Missouri is 2,547 miles. Du Pratz’s map also includes “Lahontan’s system of rivers and lakes in the North, although it labels the river running westward toward the Pacific the ‘Beautiful River’,” rather than the Long River. Lahonton’s works were extremely popular in Europe and the Long River appeared on other maps as late as 1785. The map also shows the path of Moncacht-Apé from the Missouri to the Beautiful River.[19]www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/lewis_clark/planning2.html; www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/lewis_clark/easy_comm.html; www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/lewis_clark/exploring/ch4-22.html, … Continue reading

Mackenzie’s Travel Book

Another travel book, owned by Jefferson and perhaps also by Lewis, was Alexander Mackenzie‘s Voyages from Montreal, published in 1801.[20]Alexander Mackenzie, Voyages from Montreal, on the River St. Laurence [sic] Through the Continent of North America, to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans; in the Years 1789 and 1793 (London: T. Cadell … Continue reading Mackenzie, a fur trader and partner in the Northwest Company, was the first white man to cross the continent north of Mexico. After wintering at Fort Fork on the Peace River (central Alberta, Canada), he set out in May 1793 on the last leg of his journey westward and within a month reached the northern Rockies from the east. Crossing the Continental Divide, he wrote, “We carried over the height of Land (which is only 700 yards broad) that separates those Waters, the one empties into the Northern Ocean [now named the Mackenzie], and the other [the Fraser] into the Western.” Mackenzie got onto the Fraser River, which he mistook for a northern tributary of the Columbia, but abandoned it when it became impassable, and struck out overland for the coast. Nearly two weeks later he made it to the Pacific Ocean at present-day Bella Coola, British Columbia, about four hundred miles north of the Columbia. The striking feature of this description was the relatively low ridge of mountains and the fairly easy portage, although the river was ultimately not navigable. Perhaps the mountains to the south were of similar height and the Columbia navigable at that point. Influenced by Mackenzie’s description and the theory of symmetrical geography, Jefferson and Lewis may have seen the Rockies as resembling the Appalachians in height and breadth.[21]Goetzmann and Williams, Atlas of North American Exploration, 114; Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York: Simon … Continue reading

Lewis’s Reference

There is no doubt that Lewis and Clark referred to du Pratz’s work during their journey. In a journal entry, dated 5 July 1804, Clark writes, “Mr. Du Pratz must have been badly informed as to the Cane opposd this place we have not Seen one Stalk of reed or cane on the Missouries, he States that the ‘Indians that accompanied M De Bourgmont Crossed to the Canzes Village on floats of Cane’.”[22]The passage in duPratz (p. 64) reads: “on the 8th [of July 1724] the French crossed the Missouri in a pettyaugre [small boat], the Indians on floats of cane, and the horses were swam … Continue reading The confusion arose from a faulty translation; the “canes” do not appear in the original French, which states that the Indians crossed the river in cajeux (rafts) made of unspecified materials.[23]The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, ed. Gary E. Moulton, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2: 351-352. In another document, known as the Fort Mandan Miscellany, Clark writes, “In the year 1724, they [the Paducahs] resided in several villages on the heads of the Kansas river, and could, at that time, bring upwards of two thousand men into the field (see Monsr. Dupratz history of Louisiana, page 71, and the map attached to that work).”[24]Ibid., 3: 439.

At the end of the expedition, when Lewis returned to Philadelphia in 1807, he returned du Pratz’s History of Louisiana to its owner. On the fly-leaf he inscribed: “Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton was so obliging as to lend me this copy of Monsr. Du Pratz’s history of Louisiana in June 1803. it has been since conveyed by me to the Pacific Ocean through the interior of the Continent of North America on my late tour thither and is now returned to it’s proprietor by his Friend and Obt. Servt. Meriwether Lewis, Philadelphia, May 9th, 1807.”

The inscribed book today is in the Library Company of Philadelphia. It was purchased in 1823 for $2.60 at a Philadelphia auction sale at which some books from the late Dr. Barton’s library were offered.[25]Edwin Wolf 2nd and Marie Elena Korey, eds. Quarter of a Millennium: The Library Company of Philadelphia 1731-1981 (Philadelphia: Library Company of Philadelphia, 1981), 111.

While there were other books in Lewis’s traveling library that presumably made the journey coast-to-coast, du Pratz’s History of Louisiana is the only such book the exact copy of which has been conclusively identified.

Notes

| ↑1 | Jefferson Instructions to Lewis, [20 June 1803], Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1962), 61-62. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz, Histoire de la Louisiane, 3 vols (Paris: De Bure, 1758). |

| ↑3 | Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz, History of Louisiana, edited with an introduction by Joseph G. Tregle, Jr. (London: T. Becket, 1774; reprint, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1975), xx; Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz, History of Louisiana, edited with a foreword by Stanley Clisby Arthur (London: T. Becket, 1774; reprint, New Orleans: J. S. Harmanson, 1947), 11, 18; Jennifer M. Spear, “Colonial Intimacies: Legislating Sex in French Louisiana,” William & Mary Quarterly 3d ser. 60 (2003): 81. I have cited the text of the 1947 reprint, available on the Internet at www.gutenberg.org, for details of du Pratz’s life, and the Foreword to that edition, by Arthur. References to the 1975 reprint are to the Introduction only, by Tregle. |

| ↑4 | Du Pratz, History of Louisiana (1947), 20-24; Patricia Galloway, “Rhetoric of Difference: Le Page du Pratz on African Slave Management in Eighteenth-Century Louisiana,” paper presented at the 24th Annual Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society, Monterey, California, 1998, 2. |

| ↑5 | Daniel Usner, “From African Captivity to American Slavery: The Introduction of Black Laborers to Colonial Louisiana,” Louisiana History 20 (1979): 25-48, cited in Galloway, “Rhetoric of Difference,” 2; du Pratz, History of Louisiana (1947), 70-1; Tregle, introduction to History of Louisiana (1975), xxi-xxii. |

| ↑6 | Tregle, introduction to History of Louisiana (1975), xxiii; du Pratz, History of Louisiana (1947), 85, 186-7. |

| ↑7 | Shannon Lee Dawdy, “Enlightenment from the Ground: Le Page Du Pratz’s Histoire de la Louisiane,” French Colonial History 3 (2003): 18. |

| ↑8 | Abbé de Mascrier, Mémoires historiques sur la Louisiane composés sur les mémoires de M. Dumont par M.L.L.M, 2 vols. (Paris: Buache, 1753). |

| ↑9 | Dawdy, “Enlightenment from the Ground,” 19; Tregle, introduction to History of Louisiana (1975), xxvi. |

| ↑10 | History of Louisiana, including the discovery of that vast land; its geographical description; a voyage through the territory; the natural history, the customs, dress & religion of the natives, with their origins; two voyages through northern new Mexico, to the South Sea; illustrated with two maps and 40 woodcuts. |

| ↑11 | Dawdy, “Enlightenment from the Ground,” 19-20; Arthur, foreword to History of Louisiana (1947). |

| ↑12 | Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz, History of Louisiana, or of the Western Parts of Virginia and Carolina; Containing a Description of the Countries that lye on both Sides of the River Missisippi: With an Account of the Settlements, Inhabitants, Soil, Climate, and Products (London, T. Becket, 1774); also 2 vol. (London, T. Becket and P. A. De Hondt, 1763). |

| ↑13 | Dawdy, “Enlightenment from the Ground,” 30; Arthur, foreword to History of Louisiana (1947); Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, compiled with annotations by E. Millicent Sowerby, 5 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1952-59), 4: 237. It has been suggested by Carolyn Gilman that the “quaint illustrations” of flora and fauna in du Pratz’s Histoire de la Louisiane “led Jefferson to imagine Louisiana as an abundant garden.” Gilman, Lewis and Clark, Across the Divide (Washington: Smithsonian Books, 2003), 57. But Jefferson owned the 1763 English translation of this work, which lacked all these illustrations, and it is not clear that he ever saw the French edition. |

| ↑14 | Du Pratz, History of Louisiana (1947), 59-69. |

| ↑15 | William H. Goetzmann and Glyndwr Williams, The Atlas of North American Exploration (New York: Prentice Hall, 1992), 95; James P. Ronda, introduction to Gilman, Lewis and Clark, 23; Frank W. Blackmar, ed. Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, etc., 3 vols. (Chicago: Standard Publ. Co., 1912), 1: 226-228. Transcribed on www.kansasgenealogy.com/history/bourgmont.htm. |

| ↑16 | Du Pratz, History of Louisiana (1947), 285-90. This same story appears in Dumont’s Memoires, and it is unknown who plagiarized whom. |

| ↑17 | www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/lewis_clark/easy_comm.html; Gilman, Lewis and Clark, 56. |

| ↑18 | www.finebooksmagazine.com/issue/0301/river.phtml |

| ↑19 | www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/lewis_clark/planning2.html; www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/lewis_clark/easy_comm.html; www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/lewis_clark/exploring/ch4-22.html, quoted. |

| ↑20 | Alexander Mackenzie, Voyages from Montreal, on the River St. Laurence [sic] Through the Continent of North America, to the Frozen and Pacific Oceans; in the Years 1789 and 1793 (London: T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies Strand, 1801). James Ronda notes that the last few paragraphs of the final chapter of Mackenzie’s book urged Britain, America’s nemesis, to permanently settle the West. By 1802 Jefferson had come to believe that America’s future lay in the West, and such a challenge finally convinced him to mount the Expedition. In June 1803 Jefferson wrote to James Cheetham, his bookseller, and ordered a second copy of Mackenzie, but he specifically did not want the English quarto edition because it was “too large and cumbersome”—for a voyage across the continent, perhaps? Jefferson’s library included the first volume of the two-volume edition published in Philadelphia in 1802. Ronda, introduction to Gilman, Lewis and Clark, 21, 24; Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, 4: 249-250. |

| ↑21 | Goetzmann and Williams, Atlas of North American Exploration, 114; Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 73-5; www.lib.virginia.edu/small/exhibits/lewis_clark/exploring/ch4-27.html. |

| ↑22 | The passage in duPratz (p. 64) reads: “on the 8th [of July 1724] the French crossed the Missouri in a pettyaugre [small boat], the Indians on floats of cane, and the horses were swam over.” In the margin opposite this passage Clark wrote: “no can[e] in this country.” |

| ↑23 | The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, ed. Gary E. Moulton, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2: 351-352. |

| ↑24 | Ibid., 3: 439. |

| ↑25 | Edwin Wolf 2nd and Marie Elena Korey, eds. Quarter of a Millennium: The Library Company of Philadelphia 1731-1981 (Philadelphia: Library Company of Philadelphia, 1981), 111. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.