Much of the potential Clark saw in the Yellowstone valley came to pass: a seemingly endless supply of furs and a productive agricultural resource in what would become the Yellowstone valley frontier.

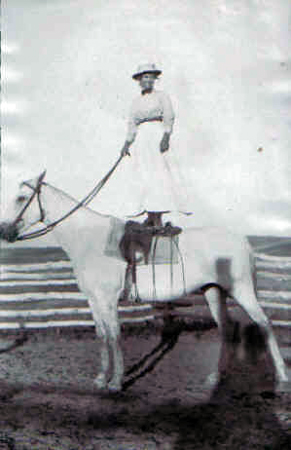

Evelyn Cameron (1868–1928), Yellowstone River Valley rancher and farmer, was a professional photographer during the pioneer days of Montana. She documented the landscape and the lives of those around Terry and Fallon, Montana. Aged 44, she and her horse, Jim, say much about the character of those who thrive in this region.[1]Kristi Hager, Evelyn Cameron: Montana’s Frontier Photographer (Helena: Farcountry Press, 2007), 1–10.

—Kristopher K. Townsend, ed.

The possibilities that captains Lewis and Clark envisioned for this “delightful land,” and the wealth its native peoples had cherished, brought EuroAmerican adventurers fast on the heels of the Corps of Discovery. And much of the potential the captains saw in the Yellowstone country came to pass. For a few years, it yielded a seemingly endless supply of furs for eastern and European markets. Ultimately, the upper two-thirds of it proved a productive agricultural resource, first as rangeland for cattle and sheep, and then as cropland, especially after the advent of irrigation around 1900. It was a failure as a navigable stream—its half-hearted steamboat era lasted less than a decade—but the Northern Pacific Railway drove its tracks, the “Main Street of the Northwest,” through the valley, opening the region and its natural resources to a wider world.

Captain Lewis had noticed coal seams in the banks near the mouth of the Yellowstone River in 1805, but he couldn’t have anticipated the importance of oil and coal deposits to the region’s future prosperity. Captain Clark’s intuition about the abundance of the river’s fishery, however, and his unalloyed admiration for the valley’s natural beauty, its riot of bankside flora, and its teeming wildlife, foreshadowed the value this rich landscape was to hold for future generations: as the basis for a multi-million dollar recreational industry and as a source of pleasure and spiritual sustenance.

The history of the Yellowstone River Valley, historian Michael Malone wrote, “exemplifies the nearly full panoply of the frontier experience.” The Yellowstone saga since 1806 includes the stories of trappers and traders, Indians restive and Indians compliant, ranchers and town builders, cowgirls and con men, homesteaders and railroaders, missionaries and prostitutes, suffragettes and labor agitators, migrant workers and leisured elites, environmentalists and industrialists, floaters and fisherfolk. Home to Billings, Montana’s largest urban area, the valley remains sparsely populated, like much of the arid West, and its river remarkably wild, given the profound—and sometimes violent—changes it has undergone since Lewis and Clark first saw that bold stream.

Notes

| ↑1 | Kristi Hager, Evelyn Cameron: Montana’s Frontier Photographer (Helena: Farcountry Press, 2007), 1–10. |

|---|