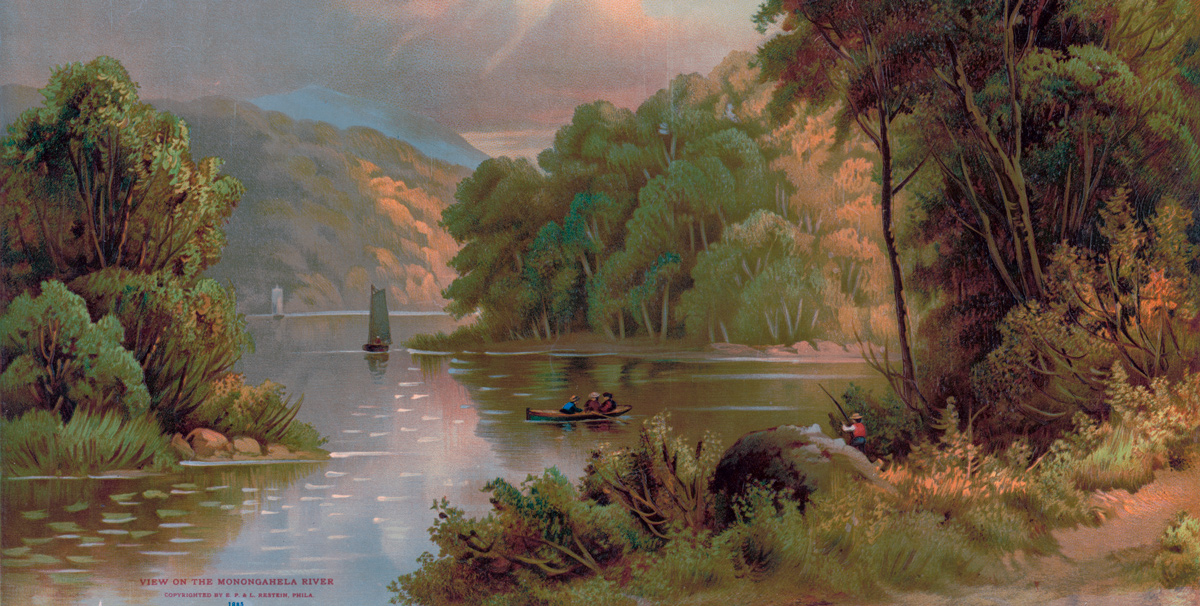

Likely on the Monongahela, Lewis travels between Brownsville and Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania on his way to Pittsburgh. If he hired a flatboat, he would travel about 32 river miles. Continuing by horse would be a shorter distance, but a more difficult day.

In Washington City, President Jefferson receives information about Mt. Hood from French naturalist Lacépède.

View on the Monongahela River

Original copyright 1885 by E. P. & L. Epstein, Philadelphia. This image is now in the Public Domain and available at the U.S. Library of Congress, loc.gov/pictures/item/2003679714/.

Elizabethtown

On his way from Harpers Ferry, Lewis turns north towards Pittsburgh, perhaps getting as far as Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania. Also in 1803, Thaddeus Harris described his travel on this route:

Twelve miles lower [than Monongahela] is Elizabethtown, on the southeast side of the river, containing about sixty houses. At this place much business is done in boat and ship building. The “Monongahela Farmer,” and other vessels of considerable burden, were built here, and, laden with the produce of the adjacent country, were sent to the West-India islands.

—Thaddeus Harris[1]Thaddeus Harris, The Journal of a Tour into the Territory Northwest of the Alleghany Mountains Made in the Spring of the Year 1803, p. 34 in Reuben G. Thwaites, Travels West of the Alleghanies … Continue reading

Vancouver’s Point

In Washington City Thomas Jefferson receives a reply about the Columbia River and Rocky Mountains from French naturalist Lacépède.

Paris, 13 May 1803

Mister President,

. . . . .

The river you seek might well be the Columbia that your compatriot Mr. Gray discovered in 1788 or 1789. Mr. Broughton, one of Captain Vancouver’s companions, navigated it northward for a hundred miles in December 1792. He stopped at a place he called Vancouver, located at latitude 45° 27′ N and longitude 237° 50′ E . . . .

. . . . .

Vancouver Point is thus still far from its source, and yet, from this place one can see Mount Hood, at a distance of about twenty leagues. Mount Hood might well be part of the Stony Mountains that Mr. Fidler[2]For more on Peter Fidler and his landmarks, see Haystack Butte, Down the Sun River, and The Bears Tooth.began to see near 40° N. The source of the Missouri must be in those Stony Mountains, between the 40th and 45th parallels.

. . . . .

B. G. É. L. LACEPÈDE[3]“To Thomas Jefferson from Lacépède, 13 May 1803,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-40-02-0275 accessed 6 May 2022. [Original source: The … Continue reading

As the Lewis and Clark Expedition would learn, Mt. Hood was part of the Cascade range in present-day Oregon. The “Stony Mountains” were four hundred miles to the east, significantly dashing the hopes of a short and easy portage between the Columbia and Mississippi drainages. See Mapping the Rockies: Expectation v. Reality and Prior Columbia River Explorers

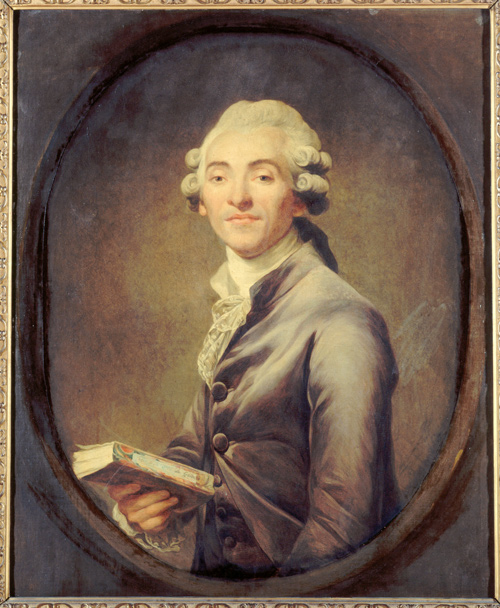

Bernard-Germain-Étienne de La Ville-sur-Illon, comte de Lacépède (c. 1785)

Joseph Ducreux (1735–1802)

88.5 cm (34.8 in) x 72.5 cm (28.5 in), Musée Carnavalet.

French naturalist, politician, freemason, accomplished musician and composer, Lacépède, or La Cépède, (1756–1825) contributed to Comte de Buffon’s Histoire Naturelle and in 1803, his fifth volume of Histoire naturelle des poissons appeared. Both he and Thomas Jefferson were members of the French Academy of Sciences at the Institute of France.[4]See also Buffon to Jefferson in February 24, 1803.

Lacépède’s Enlightenment

Whatever the outcome of the exploration you are commissioning, it will be extremely useful for the progress of industry, science, and, especially, natural history. May your fellow citizens, by the wisdom of their decisions, forever preserve their liberty, their government, and peace! Until now, the movement of enlightenment has been from east to west. Unless the inhabitants of the United States reject their destiny, they will one day check this movement and reverse it.

Accept, Mister President, the expression of my warm admiration, my deep gratitude and my respect.

B. G. É. L. LACEPÈDE[5]Ibid.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to July 14, 1803:

- Harpers Ferry to Brownsville (Inspiration Trip)

Notes

| ↑1 | Thaddeus Harris, The Journal of a Tour into the Territory Northwest of the Alleghany Mountains Made in the Spring of the Year 1803, p. 34 in Reuben G. Thwaites, Travels West of the Alleghanies (Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Co., 1904), p. 337–38. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For more on Peter Fidler and his landmarks, see Haystack Butte, Down the Sun River, and The Bears Tooth. |

| ↑3 | “To Thomas Jefferson from Lacépède, 13 May 1803,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-40-02-0275 accessed 6 May 2022. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 40, 4 March–10 July 1803, ed. Barbara B. Oberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013, pp. 367–370.] |

| ↑4 | See also Buffon to Jefferson in February 24, 1803. |

| ↑5 | Ibid. |