Richard McCourt

Associate Curator of Botany, The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Richard M. McCourt earned his undergraduate degree in botany at Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Oregon, and his M.A. and Ph.D. at the University of Arizona. His research on green algae helped answer a long-standing question about the evolution of land plants from aquatic ancestors. One of his first major undertakings at the Academy of Natural Sciences was to lead a project to renovate the storage conditions of the Lewis and Clark Herbarium. He has coauthored several articles on the history and scientific uses of the collection, and coordinated presentations of the specimens at venues around the country.

Earlier in his professional career he worked at WGBH in Boston as a staff reporter, and became a regular freelancer for National Public Radio, reporting on topics ranging from the search for new planets and solar systems to the medicinal uses of leeches.

Contributions

Georges Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, was the most influential biologist of the 18th century. The title of Count was bestowed not by birth, but by Louis XV in recognition of his accomplishments.

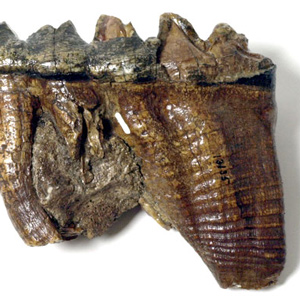

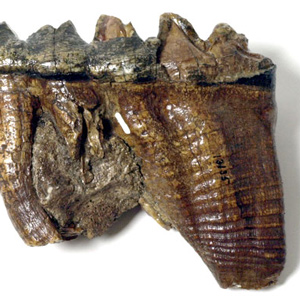

On 6 August 1804, Sgt. Patrick Gass found the one fossil known to survive from the expedition today. The data were recorded by Lewis on a tag that accompanied the so-called Fort Mandan shipment, the first batch of specimens to be sent back East from Fort Mandan, in 1805.

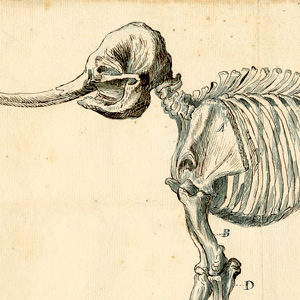

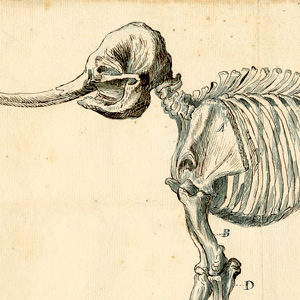

After leaving Pittsburgh, Lewis had his first two opportunities to personally delve into the new science of paleontology. One was a trip to Big Bone Lick, a natural salt lick and fossil bed more than 15,000 years old, situated in Kentucky less than 20 miles southwest of Cincinnati.

In Cuvier’s time, the idea of extinction was entertained, but it was still in dispute. What was most difficult to ascertain was what extinction meant in understanding the history of the earth.

The American fauna was not made up of degenerate forms of Old World animals. And it was not beyond the realm of possibility to find those elusive mastodons and megalonyxes alive. To imagine this sort of thing must have inspired awe in Lewis.

For Meriwether Lewis, the theory of extinction was a philosophical argument, not a foregone conclusion. He might even have wondered how he would deal with a live mastodon if he came across one.

The Fort Mandan shipment of specimens was registered in the so-called “Donation Book” that was compiled for the Lewis and Clark materials received in November 1805. The entries were sequentially numbered by John Vaughan of the APS in Philadelphia.

Would Lewis recognize living animals, examples of which he had seen only as bones in Philadelphia? Would the hunting parties of the corps unexpectedly find herds of mastodons, and packs of stealthy predators, or a lumbering solitary grazer previously never seen by humans?

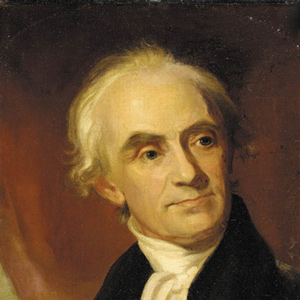

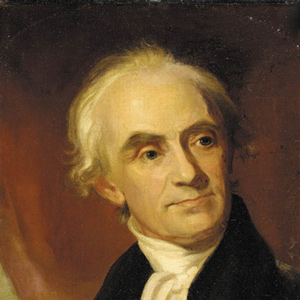

The son of a farmer and merchant in Philadelphia, Richard Harlan became a leading American figure in anatomical studies. He would become the man who named the only fossil that now survives from the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Thomas Jefferson first believed them to be from a kind of lion, which he thought might still survive in the distant wilds of western America. No doubt Lewis had held them too and would be looking for live specimens.

There is a great abundance of a species of bear-grass which grows on every part of these mountains,” wrote Lewis on 15 June 1806. “It’s growth is luxouriant and continues green all winter but the horses will not eat it.”

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.