Retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel and former chief historian of the National Guard Bureau Sherman Fleek discusses frontier army life in 1803 and the exemplary military leadership of the co-captains and non-commissioned officers.[1]Extracts from Sherman L. Fleek, “The Army of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 30 No. 4, November 2004, 8–14. The original full-length article is available at our sister site, … Continue reading.

Army Life

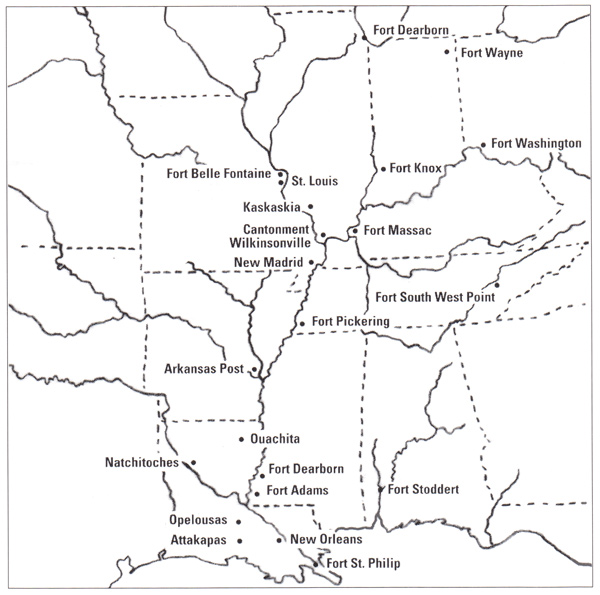

Line units were spread out in small garrisons over hundreds of miles of the frontier. [See map] There was no formal recruiting system as we know it today, and post commanders usually drew their men from the local population. The army made no effort to systematically educate its commissioned and non-commissioned officers (N.C.O.s). There were no professional or leadership schools, no career-advancement programs, and no specialized training beyond simple skill sets and tactical drilling. Promotion was based on seniority rather than fitness. With no retirement system, officers tended to stay in the service as long as possible. Low pay sometimes forced officers to moonlight as postmasters, justices of the peace, surveyors, and school teachers, while enlisted men found jobs as laborers and farm hands. Pay day at the many small garrisons depended on circuit-riding paymasters (Lewis was one), who thanks to the vagaries of frontier travel could arrive days, weeks, or months later than scheduled.[2]Edward M. Coffman, The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784–1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 30.

Garrison life was tedious and filled with the routine of drill, inspection, standing guard, and a wide range of fatigue duties, from cutting and hauling firewood to digging latrines.[3]Robert J. Moore, Jr., and Michael Haynes, Tailor Made, Trail Worn: Army Life, Clothing & Weapons of the Corps of Discovery (Helena, Mont.: Farcountry Press, 2003), 30–41. Diet, medical care, and living conditions in general ranged from adequate to abysmal. Alcohol abuse was chronic. The hard life drove as many as one man in five to go absent without leave or to desert, offenses that accounted for about half of all court-martial cases.[4]Coffman, 21. Whatever the charge, those found guilty of even minor offenses were often flogged (the Articles of War allowed up to 100 lashes).[5]Moore and Haynes, 51.

Lewis and Clark could be tough disciplinarians when necessary. Early in the expedition, three privates were flogged and one was forced to run the gauntlet; two of these four men were expelled from the corps. But such punishments were generally reserved for offenses that threatened the unit’s cohesion or even survival, including disrespect toward superiors, drinking on guard, and desertion.[6]Four men were court-martialed during the expedition. Hugh Hall received 25 lashes for going AWOL and 50 lashes for being drunk on guard. John Collins received 100 lashes for disrespect and drinking … Continue reading For lesser offenses the captains often showed flexibility and restraint, handling cases administratively instead of by court martial. When two privates got into a fist-fight at Camp River Dubois, for example, Clark ordered them to work together to build a hut for the camp’s laundress. Later, when some of the men balked at following one of the sergeant’s orders, they were confined to camp for ten days.[7]Ibid., 57.

Military Leadership

The captain’s deft employment of discipline was just one of many examples of their leadership qualities. During the expedition and throughout their army careers Meriwether Lewis and Williams Clark exhibited resourcefulness, initiative, self-reliance, courage, and physical and mental toughness. To a greater or lesser extent such traits were also common to the Corps of Discovery’s non-commissioned officers—its sergeants (Charles Floyd, Patrick Gass, John Ordway, and Nathaniel Pryor) and sole corporal (Richard Warfington)—and could be found throughout the army’s ranks of officers and N.C.O.s. It is reasonable to attribute these qualities at least in part to the challenges faced by so many American males growing up on the nation’s back country farmsteads. Although born into relative privilege, the expedition’s co-captains both fit this model. Clark, who spent his formative teenage years on the Kentucky frontier, was described by an uncle as “a youth of solid and promising parts and as brave as Caesar.”[8]James O’Fallon to Jonathan Clark, 30 May 1791; Jay Buckley, William Clark: Superintendent of Indian Affairs at St. Louis, 1813-1838 (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Nebraska, 2001), 11. Lewis passed three boyhood years on the Georgia frontier, where his biographer Stephen Ambrose imagines him hunting, fishing, exploring, learning about Indians, and “growing comfortable with life in the wilderness.”[9]Ambrose, 24; James P. Hendrix, Jr., “Meriwether Lewis’s Georgia Boyhood,” We Proceeded On, August 2001, 25-28 available at our sister site at … Continue reading

With the exception of Floyd, who died early in the expedition, each of the corps’ N.C.O.s was entrusted with extraordinary responsibilities, and they carried them out in exemplary fashion. Warfington, who wasn’t part of the permanent party, commanded the expedition’s keelboat [the barge] when it returned to St. Louis in the spring of 1805 loaded with plant and wildlife specimens. Warfington negotiated the country of the troublesome Teton Sioux without incident, and Gass, Ordway, and Prior each led separate parties on the homeward journey.[10]For Sgt. Pryor, see Pryor’s Mission.

Counterexample: The Astorians

Anyone who doubts the importance of military leadership and discipline in the Corps of Discovery’s success should ponder the debacle, five years later, of the overland Astorians. In May 1811, a civilian party outfitted by fur merchant John Jacob Astor set out from St. Louis for Astoria, his post at the mouth of the Columbia, via the Missouri and Platte rivers. The expedition crossed the Wind River Mountains and descended to the Green and Snake rivers. Things went well enough on the plains but started to unravel when the explorers reached the Rockies and switched from horses to dugout canoes. The idea was to run the Snake to the Columbia, but when the ferocious river smashed their boats, they abandoned them and set out on foot. Split into smaller groups, they staggered into Astoria in stages—some reaching it in January 1812, some in February and May, the last in January 1813. Their collective tale was a litany of drownings, desertions, intense cold and hunger, and harassment by Indians.

The return trip, begun in June 1812, proved no less harrowing. Men became disoriented and wandered in circles in the wilderness. Several died, one went insane, and one starving wretch talked openly of cannibalism, suggesting that his party draw straws to determine who would eat whom. With help from the ever-friendly Shoshones, most survived the ordeal and reached St. Louis the following spring.[11]Hiram Martin Chittenden, The American Fur Trade of the Far West, 2 volumes (New York: Press of the Pioneers, 1935; reprint Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 1:182-215.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition faced similar trials, particularly the brutal crossing of the Bitterroots, when the explorers endured bitter cold and near-starvation. Morale may have dipped on such occasions but never seriously flagged, because military leadership and organization proved more than equal to the challenge.

Notes

| ↑1 | Extracts from Sherman L. Fleek, “The Army of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 30 No. 4, November 2004, 8–14. The original full-length article is available at our sister site, lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol30no4.pdf#page=9 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Edward M. Coffman, The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784–1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 30. |

| ↑3 | Robert J. Moore, Jr., and Michael Haynes, Tailor Made, Trail Worn: Army Life, Clothing & Weapons of the Corps of Discovery (Helena, Mont.: Farcountry Press, 2003), 30–41. |

| ↑4 | Coffman, 21. |

| ↑5 | Moore and Haynes, 51. |

| ↑6 | Four men were court-martialed during the expedition. Hugh Hall received 25 lashes for going AWOL and 50 lashes for being drunk on guard. John Collins received 100 lashes for disrespect and drinking on guard. Moses Reed was convicted of desertion and sentenced to run the gauntlet. John Newman got 75 lashes for mutiny. Reed and Newman were both expelled from the Corps of Discovery and returned to St. Louis after spending the winter at Fort Mandan. Elin Woodger and Brandon Toropov, Encyclopedia of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (New York: Facts-on-File, 2004), 93, 115–116, 167, 249, and 299. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 57. |

| ↑8 | James O’Fallon to Jonathan Clark, 30 May 1791; Jay Buckley, William Clark: Superintendent of Indian Affairs at St. Louis, 1813-1838 (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Nebraska, 2001), 11. |

| ↑9 | Ambrose, 24; James P. Hendrix, Jr., “Meriwether Lewis’s Georgia Boyhood,” We Proceeded On, August 2001, 25-28 available at our sister site at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol27no3.pdf#page=26. |

| ↑10 | For Sgt. Pryor, see Pryor’s Mission. |

| ↑11 | Hiram Martin Chittenden, The American Fur Trade of the Far West, 2 volumes (New York: Press of the Pioneers, 1935; reprint Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 1:182-215. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.