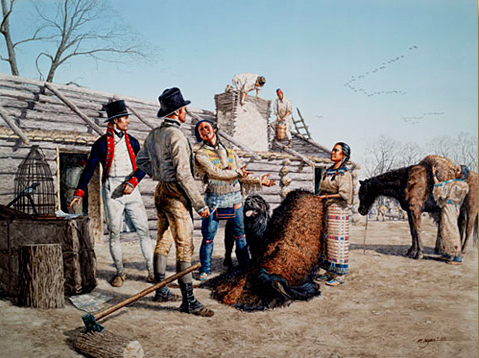

Charbonneau’s Buffalo Robes

© Michael Haynes, https://www.mhaynesart.com. Used with permission.

It is Sunday, 11 November 1804. As the men of the Corps of Discovery work steadily to complete the construction of Fort Mandan before the coming Northern Plains winter—heralded by the cacaphony of two flocks of southbound Canada geese—Toussaint Charbonneau and his two wives, both of the Snake (Shoshone) nation, come to call. While Lewis’s Newfoundland dog, Seaman, looks on, Charbonneau presents “4 buffalow Robes” as gifts, according to Sergeant Ordway’s journal for the day.

This most likely was Meriwether Lewis‘s and William Clark‘s first encounter with the woman who was to play a significant role in the success of the expedition, not as a guide, as the old legend has it, but as an interpreter—with Charbonneau’s help—between the captains and her people. Her name is Sacagawea, a teen-age girl about 17 years of age who was captured by Hidatsa warriors at the Three Forks of the Missouri when she was about 12, and raised through puberty in Metaharta, a Hidatsa village at the mouth of the Knife River.

In the cage at Lewis’s right a magpie adds its raucous voice to the morning’s general clatter and chatter. Lewis will ship it back to President Jefferson on the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) the following spring.

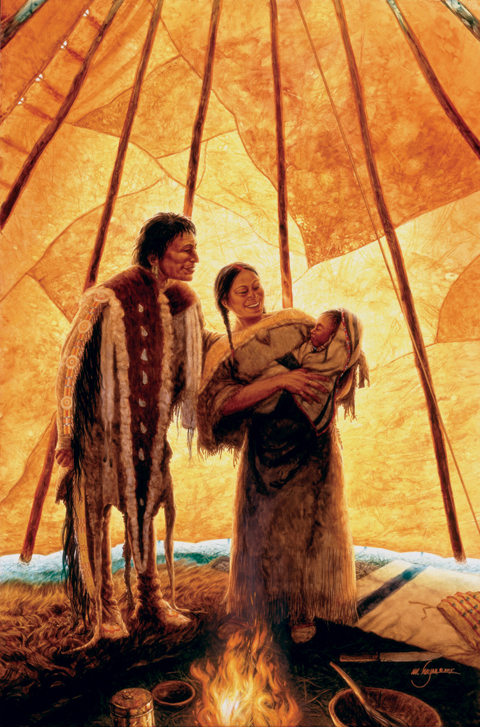

Jean Baptiste and Sacagawea

by Carol Grende

© 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Sacagawea at Fort Osage

© 2015 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The text of the plaque reads:

Sacagawea, famous member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition,

while traveling up the Missouri River from St. Louis to the

Northern Plains area, stayed the night at Fort Osage.

On Thursday April 25, 1811, as a member of a group of travelers led by

Manuel Lisa, Sacagawea, along with her husband Toussaint Charbonneau,

arrived at Fort Osage, spent the night and departed the next morning.

This event is documented in the

“Journal Of A Voyage Up The Missouri River In 1811”

by Henry Marie Brackenridge.

This Plaque was presented to Fort Osage on

the Bicentennial of this event, April 25, 2011,

by the Missouri-Kansas River Bend Chapter

of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation

and the Native Sons and Daughters of Greater Kansas City.

His Sister’s Son

by Michael Haynes

© 2006 Michael Haynes. Reproduction prohibited without artist’s permission.

Watercolor, 24 by 36 inches. The artist may be contacted at Michael Haynes, Historic Art

One of the best-known episodes in the whole story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition is the surprise reunion of the party’s “interpretess,” Sacagawea, with her brother, Cameahwait, the “Great Chief” of the Lemhi Shoshones. It was recorded briefly and matter-of-factly by Meriwether Lewis. In artist Michael Haynes’s conception of a brief and tender moment, otherwise undocumented, the proud young mother smiles broadly as if to tease little Jean Baptiste Charbonneau into responding similarly toward his uncle. Cameahwait, whom Clark called “a man of Influence Sence & easey & reserved manners, [who] appears to possess a great deel of Cincerity,”[1]Moulton, ed., Journals, 5:114, 17 August 1805. seems to be speaking softly to the 6-month-old baby. The Chief is wearing a tippet, that “most eligant peice of Indian dress,” much like the one he later gave to Meriwether Lewis. (See Lewis’s Shoshone Tippet.)

The scene is inside the leather lodge Lewis purchased from Toussaint Charbonneau at Fort Mandan.[2]“Settled with Touisant Chabono for his Services as an enterpreter the price of a horse and Lodge purchased of him for public Service in all amounting to 500$ 33 1/3 cents.” Ibid., 8:305, … Continue reading Nightly from early April until mid-November, 1805, it sheltered the two captains and Clark’s servant, York, interpreters George Drouillard and Toussaint Charbonneau, Toussaint’s wife Sacagawea, and Jean Baptiste. While Lewis searched for a suitable site for their winter encampment near the mouth of the Columbia River, the rest of the company fought to survive torrential wind and rain on Tongue Point near today’s Astoria, Oregon. Clark reported on 28 November 1806, “we are all wet bedding and Stores, haveing nothing to keep our Selves of Stores dry, our Lodge nearly worn out, and the pieces of Sales & tents So full of holes & rotten that they will not keep anything dry.”[3]Ibid., 6:91, 28 November 1806.

Sacagawea and Cameahwait had not seen one another since their hunting camp near the Three Forks was attacked by Minitare (Hidatsa) warriors in about the year 1800. She and her sister, along with some other females and four boys, were captured by Hidatsa warriors and carried off to their village on the Missouri River near the mouth of the Knife in today’s North Dakota. On 28 July 1805 the Corps of Discovery camped on the exact spot where that attack took place.[4]Ibid., 5:8-9.

—Joseph A. Mussulman

She appeared in the captains’ journals four times before her name was given. She was with the expedition for just over 16 of the 28 months of the official journey. Speaking both Shoshone and Hidatsa, she served as a link in the communication chain during some crucial negotiations, but was not on the expedition’s payroll. She traveled nearly half the trail carrying her infant on her back. And, despite artistic portrayals of her pointing the way, she “guided” only a few times. Still, Sacagawea remains the third most famous member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

In the fall of 1804, Sacagawea was around seventeen years old, the pregnant second wife of French Canadian trader Toussaint Charbonneau, and living in Metaharta, the middle Hidatsa village on the Knife River of western North Dakota. Born into a tribe of Shoshones who still live on the Salmon River in the state of Idaho, she had been among a number of women and children captured by Hidatsas who raided their camp near the Missouri River’s headwaters about five years previously. Both of Charbonneau’s wives were captured Shoshones.

Not long after the captains selected their winter site for 1804-1805, the Charbonneau family went a few miles south to the Mandan villages to meet the strangers. William Clark‘s journal entry of 11 November 1804, mentioned them impersonally: “two Squars[5]For more, see Defining ‘Squaw’. of the Rock Mountain, purchased from the Indians by . . . a frenchmen Came down.” The captains promptly hired Charbonneau as their Hidatsa translator, and René Jusseaume as their temporary Mandan translator. Both men and their Indian wives moved into Fort Mandan.

Jean Baptiste’s Birth

At dusk on 11 February 1805, Sacagawea’s difficult first childbirth produced a healthy boy, who would be named Jean Baptiste Charbonneau after his grandfather.[6]Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 188, lists Toussaint Charbonneau’s parents as … Continue reading In the late stages of her labor, Jusseaume mentioned that a little rattlesnake rattle, moistened with water, would speed the process. Lewis wrote:

having the rattle of a snake by me I gave it to him and he administered two rings of it to the woman. . . . Whether this medicine was truly the cause or not I shall not undertake to determine, but I was informed that she had not taken it more than ten minutes before she brought forth . . . I must confess that I want faith as to it’s efficacy.

We see that Meriwether Lewis neither was directly present at nor assisting in the birth, as he often has been credited, and that the scientific question raised was of more interest to him.

Leaving Fort Mandan

On 7 April 1805, as the Corps set out from Fort Mandan, Lewis listed all those in the permanent party, including “an Indian Woman wife to Charbono with a young child.” In his duplication of the list, Clark added “Shabonah and his Indian Squar to act as an Interpreter & interpretress for the snake Indians . . . & Shabonahs infant. Sah-kah-gar we a“

Historian Gary Moulton speculates that the name may have been added later, after Clark became better acquainted with her. It is appropriate that Clark was the first to refer to her by name, because he developed much more of a protective friendship with the young mother and her child than did Lewis. The captains and Drouillard shared the Charbonneaus’ leather tipi until it rotted away late in 1805, so both captains knew her well. While Lewis admired Sacagawea’s poise in crisis, caring for her during a serious illness happened to fall to Clark. That seemed to initiate a special friendship between Clark and the Charbonneau family—one with lifelong consequences for Jean Baptiste.

Helping Out

Only two days out from Fort Mandan, Sacagawea began sharing her knowledge of native foods, to the Corps’ benefit. Lewis wrote:

when we halted for dinner the squaw busied herself in serching for the wild artichokes[7]Actually hog peanuts, Amphicarpa bracteata, which meadow mice or voles collect and store. Moulton, ed., Journals, 4:18n6. which the mice collect and deposit in large hoards. this operation she performed by penetrating the earth with a sharp stick about some small collections of drift wood. her labour soon proved successful, and she procurrd a good quantity of these roots

On 8 May 1805, Sacagawea gathered what Lewis labeled “wild Likerish, & the white apple [breadroot][8]The large Indian breadroot, formerly known as Psoralea esculenta, is a member of the pea family now known as Pediomelum esculentum—pee-dee-oh-MEE-lum “plain apple” and ess-kyu-LEN-tum … Continue reading as called by the angegies [engagés] and gave me to eat, the Indians of the Missouri make great use of the white apple dressed in different ways.” The year before, only York was reported to have gathered fresh vegetable food, some “cresses,” to vary the Corps’ diet.

When Charbonneau panicked during a boat upset on 15 May 1805, Lewis credited Pierre Cruzatte with saving the boat itself. The next day he added:

the Indian woman to whom I ascribe equal fortitude and resolution, with any person on board at the time of the accedent, caught and preserved most of the light articles which were washed overboard

Four days after that entry, the captains named “a handsome river of about fifty yards in width” the Sacagawea “or bird woman’s River, after our interpreter the Snake woman.”[9]Although it was known as Crooked Creek for many years, the name Sacagawea River has been restored. Ibid., 4:175n5. The Sacagawea River empties into the Musselshell a few miles south of where the latter joins the Missouri in northeastern Montana.

Illness

During the portage around the Great Falls of the Missouri, Sacagawea was quite ill for ten days, and Clark was her caregiver. His delicate description of what he took to be a female complaint leads modern physician David J. Peck, D.O., to consider pelvic inflammatory disease—from a venereal infection transmitted by her husband—but Dr. Peck also points out that the recorded symptoms could match those of a Trichinella parasite infection from recently consumed grizzly bear meat. (Lewis suffered a “violent pain in the intestens” at the same time, which he treated on 11 June 1805 by brewing some chokecherry-bark tea.) Clark utilized state-of-the-art, if useless, bleeding and purging techniques on Sacagawea, but antibiotics were needed. He believed that Sacagawea’s health improved after he had her drink water from the nearby sulfur spring.[10]David J. Peck, Or Perish in the Attempt: Wilderness Medicine in the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Helena, MT: Farcountry Press, 2002, 161-62.

On the 20th, Lewis was able to write that she was “walking about and fishing.” She had been well the day before, then gathered some breadroot and ate the roots:

heartily in their raw state together with a considerable quantity of dryed fish without my knowledge . . . she complained very much and her fever again returned. I rebuked Sharbono severely for suffering her to indulge herself with such food he being privy to it and having been previously told what she must only eat.

Flash Flood

While Clark was walking on the prairie near the falls with the three Charbonneaus on 29 June 1805, they were caught in a rain-and-hail storm and its resulting flash flood. After recounting how their shelter in a ravine turned into a trap when flood waters rolled in, and how Charbonneau froze while Clark pushed his wife up from the ravine, Clark’s concern turned to her baby and her still-fragile health. He sent men—themselves just caught in the open transporting cargo, and cut and bruised by hail—rushing to Portage Camp to grab replacements for lost clothing:

I directed the party to return to the Camp at the run as fast as possible to get to our lode where Clothes Could be got to Cover the Child whose Clothes were all lost, and the woman who was but just recovering from a Severe indisposition, and was wet and Cold, I was fearfull of a relaps[11]See also A Flash Flood.

Recognizing—not Guiding

As the Corps worked hard poling the boats up a stretch of Missouri now under Canyon Ferry Lake north of Townsend, Montana, on 22 July 1805:

The Indian woman recognizes the country and assures us that this is the river on which her relations [the Shoshones] live, and that the three forks are at no great distance. this peice of information has cheered the sperits of the party who now begin to console themselves with the anticipation of shortly seeing the head of the missouri yet unknown to the civilized world. [Lewis]

Welcome news, indeed—but not quite “guiding.” Lewis was not quite ready to trust Sacagawea’s six-year-old memories. After all, the Hidatsas who told about the Great Falls portrayed them as a single fall that took one day to pass around. On 24 July 1805, he admitted,

I fear every day that we shall meet with some considerable falls or obstruction in the river notwithstanding the information of the Indian woman to the contrary who assures us that the river continues much as we see it. I can scarcely form an idea of a river runing to great extent through such a rough mountainous country without having it’s stream intersepted by some difficult and gangerous [sic] rappids or falls.

On the 30th, near today’s town of Three Forks, Montana (a few miles southwest of the confluence of the Missouri’s headwaters), Lewis was walking with the Charbonneaus when Sacagawea suddenly stopped and said they were exactly where the Hidatsas had captured her.

While Lewis never commented that her headwaters information had proved correct, the next time Sacagawea recognized a landmark, on 8 August 1805, he was ready to act on her knowledge. The Corps were now moving up the Beaverhead River in southwestern Montana, when

the Indian woman recognized the point of a high plain to our right which she informed us was not very distant from the summer retreat of her nation on a river beyond the mountains. . . . this hill she says her nation calls the beaver’s head [Beaverhead Rock] from a conceived resemblance. . . . she assures us that we shall either find her people on this river on the river immediately west of it’s source. . . . as it is now all important with us to meet with those people as soon as possible, I determined . . . to proceed tomorrow with a small party . . . until I found the Indians.

Among the Shoshones

Thus it was that Lewis found Cameahwait’s band of Shoshones and urged them to go with him back to “my brother captain” and the party that included “a woman of his nation.” Reluctantly, fearing a Blackfeet ambush, Chief Cameahwait and some of his people did agree to go—when Lewis and his men promised to switch clothing with the Shoshones. On the morning of 17 August 1805, Clark was walking behind Sacagawea and Charbonneau when Lewis and his men appeared in the distance, their Shoshone clothing recognizable before their faces were.

The Intertrepeter & Squar who were before me at Some distance danced for the joyful Sight, and She made signs to me that they were her nation . . . . The Great Chief of this nation proved to be the brother of the Woman with us and is a man of Influence.

Lewis wrote that:

Capt. Clark arrived with the Interpreter Charbono and the Indian woman, who proved to be a sister of the Chif Cameahwait. the meeting of those people was really affecting, particularly between Sah ca-gar-we-ah and an Indian woman, who had been taken prisoner at the same time with her, and who had afterwards escaped from the [Hidatsas] and rejoined her nation.

The whites could understand only the display of universal human emotions before them when greetings, news, and introductions of husband and baby were exchanged in the Shoshone tongue. That evening, serious discussion began, with a translation chain—from the captains to François Labiche to Charbonneau to Sacagawea to Cameahwait, and back. The “interpretess” was now at work, beginning her most significant contribution to the expedition.

The Shoshones’ aid was more than generous, selling horses, carrying cargo, sharing knowledge of the Bitterroot Mountains and the Columbia River’s highest waters, and supplying a guide to take the Corps to and across the Northern Nez Perce Trail over the Bitterroots.

Token of Peace

During that harrowing, starving trek, the journals are silent on how Sacagawea and her infant fared. Her leave-taking of her own people also went unrecorded. She is absent from the captains’ journals until 13 October 1805, when the Corps is on the Columbia below the Palouse River, and Clark writes, “The wife of Shabono our interpetr we find reconsiles all the Indians, as to our friendly intentions[.] a woman with a party of men is a token of peace”

He gave a more detailed example on 19 October 1805, when Clark, Drouillard and the Field brothers were walking on the Columbia’s Washington side ahead of the canoes. Reaching a village of Umatillas near present Plymouth, the whites found men, women, and children hiding in terror. Clark emptied his pockets and made gifts, but could not persuade the men to come outdoors and smoke with him—an invitation given while freely entering their woven-mat lodges as if asked! Only five men ventured out, saying that the whites “came from the clouds &c &c& . . . and were not men &c. &c.” Then the canoes hove into view, and the Umatillas came out of their homes—

as Soon as they Saw the Squar wife of the interperters . . . they pointed to her and informed those [still indoors, who] imediately all came out and appeared to assume new life, the sight of This Indian woman . . . confirmed those people of our friendly intentions, as no woman ever accompanies a war party of Indians in this quarter.

After reaching the Columbia’s estuary and exploring the Washington side for a winter site, the captains held the third of their advisory polls, on 24 November 1805.[12]The earlier ones were on 22 August 1804, for nomination of a sergeant to replace the deceased Floyd, and 9 June 1805 on which “fork” at the Missouri-Marias confluence to follow. The choices were to cross and see what the Oregon side offered, or go back upstream, specifically to either The Dalles or the Sandy River. Only Charbonneau expressed no opinion. York was for checking the Oregon side, and Sacagawea’s comment—recorded below the individual and totalled ballots that included York’s—Clark wrote as “Janey[:] in favour of a place where there is plenty of Potas [“potatoes,” or edible roots of any kind].” Were the captains socially forward-looking? Definitely not. But this “vote” suggests how the small band of interdependent companions existed on the practical level for its own survival, temporarily outside of time and culture and Army regulations. And practical the young mother was in her suggestion. “Janey”? The warmth of a nickname is stunning in Clark’s journal pages, but no explanation comes. Nor is the word ever repeated in the journals.[13]Clark used the name again when writing to Toussaint Charbonneau from the Arikara villages on the Missouri on 20 August 1806, to reiterate his invitation: ” . . . bring down you Son your famn … Continue reading

Most of the Corps stayed at a base camp on Tongue Point, Oregon, while Lewis and some men scouted for a wintering site in early December. On the 2nd, Joseph Field brought in the marrow bones[14]Long bones of the upper leg, which are filled with fatty connective tissue where blood cells are produced. of “the first Elk we have killed on this Side the rocky mounts,” and the next day Sacagawea rendered the fat from them. Clark, who was ailing from the diet of pounded salmon, said the “Grease . . . is Superior to the tallow of the animal.” It would make a nourishing broth, but Clark did not say how he came to taste it, and whether Sacagawea prepared it for him.

While mentioned a few times as gathering wild plants for food, Sacagawea is portrayed as cook only twice. A few days before the marrow bones, on 30 November 1805, Clark had written:

The Squar gave me a piece of bread made of flour which She had reserved [the Corps’ last mentioned use of flour was nearly three months before] for her child and carefully Kept until this time, which has unfortunately got wet, and a little Sour—this bread I eate with great Satisfaction, it being the only mouthfull I had tasted for Several months past.

At the Pacific

On 20 November 1805, Sacagawea played banker for the Corps. The Clatsop chief Coboway visited, and one of the people with him displayed a “robe” made of sea otter, “more butifull than any fur I had ever Seen” (Clark). Both captains offered several trade articles for it and were turned down (Ordway noted that the Clatsops would accept only blue beads, and Whitehouse that these were the most valuable to them). But “at length we precured it for a belt of blue beeds which the Squar . . . wore around her waste” (Clark). The next day, her loan was repaid with “a Coate of Blue cloth.”

Clark wrote on Christmas 1805 about the “pore” celebration dinner, and also listed the gifts he received, including “two Dozen white weazils tails of the Indian woman.”[15]Moulton identifies these as likely from the long-tailed weasel, Mustela frenata, 6:138n2. Where and how she obtained them is unknown. It seems likely that she had observed how French and British traders visiting or living among the Hidatsas celebrated their winter holiday, and she may have learned more about Christmas from her Catholic husband.

On 5 January 1806, Alexander Willard and Peter Weiser returned from helping set up Salt Camp. They brought in some blubber obtained from the Tillamooks at NeCus’ Village, who were butchering a beached whale near Salt Camp. After Fort Clatsop residents cooked and ate some, Clark decided to take twelve men and try to trade for a supply. This drew a reaction from Sacagawea that Clark recorded the next day, preserving a glimpse of her personality and curiosity about the world:

The last evening Shabono and his Indian woman was very impatient to be permitted to go with me, and was therefore indulged; She observed that She had traveled a long way with us to See the great waters, and that now that monstrous fish was also to be Seen, She thought it verry hard that She Could not be permitted to See either (She had never yet been to the Ocian).

Of the trip, Clark waxed romantic about the ocean—”the grandest and most pleasing prospects which my eyes ever surveyed, in my frount a boundless Ocean . . . the Seas rageing with emence wave and brakeing with great force from the rocks”—and described the hardship of climbing over Tillamook Head burdened with blubber, but did not mention Sacagawea or her reactions.

To the Yellowstone

From 22 May 1806 to 8 June 1806, at Long Camp, Sacagawea’s attention had to be focused on her son. Jean Baptiste, now fifteen months old, was having a difficult time teething, and also had an abscess on his neck. Clark served as primary physician, dosing the boy with laxatives. For his swollen neck, “we still apply polices [poultices] of onions which we renew frequently in the course of the day and night.” While the warm heat would have comforted the child, the poultices did nothing for the abscess that Clark suspected. On 3 June 1806, Lewis reported that the swelling had greatly subsided, and on the 8th Clark wrote that “the Child has nearly recovered.”[16]A more detailed description of the course of treatment appears in Peck, 252-53.

One wonders whether Sacagawea hoped to see her Shoshone people again on the Corps’ return trip. She and her family were in Clark’s party heading to the Yellowstone River, which traveled north of the Shoshones’ country en route to Camp Fortunate—and the month was July, too early for the Shoshones’ annual buffalo hunting trip east of the mountains.

The route again took Sacagawea into lands she remembered from childhood. On 6 July 1806, three days after Lewis’s and Clark’s parties split at Travelers’ Rest, Clark’s group reached the Big Hole Valley of southwestern Montana, “an open boutifull Leavel Vally or plain of about 20 Miles wide and hear 60 long[17]Nicholas Biddle, with information from William Clark or George Shannon, amended the measurements to 15 miles by 30. extending N & S. in every direction around which I could see high points of Mountains Covered with Snow.” Sacagawea had visited this spot on camascamas-gathering trips as a girl, and pointed—guided—the way to Big Hole Pass on present Carroll Hill, the Big Hole’s easy eastern exit, crossed today by a state highway.

When Clark’s still-smaller party—without Ordway and nine men who were taking the canoes down the Missouri—moved east of the Three Forks of the Missouri on 13 July 1806, they passed out of land familiar from the previous year’s trip. But Sacagawea still was on familiar turf, and knew the way to the Yellowstone. Clark commented that “The indian woman who has been of great Service to me as a pilot through this Country recommends a gap in the mountain more South which I shall cross.” This led the party up to today’s Bozeman Pass in the Bridger Range.[18]Modern Interstate 90 crosses Bozeman Pass between Bozeman and Livingston, Montana.

During the trip down the Yellowstone River, from 15 July 1806 to 3 August 1806, Sacagawea disappears from Clark’s journal, but her son comes to the fore. On 25 July 1806, Clark climbed a 200-feet-tall sandstone column that rose beside the Yellowstone (east of today’s Billings), and carved his name and the date after enjoying “from it’s top . . . a most extensive view in every direction.” He named the rock “Pompy’s Tower” using his personal nickname for the boy.

On the lower Yellowstone in August, everyone suffered greatly from mosquito bites, the men’s “mosquito biers,” or nets, now being in tatters. But little “Pompy,” whose bier had been swept away by that flash flood at the Falls of the Missouri, suffered the most. On 4 August 1806 Clark wrote sympathetically, “The Child of Shabono has been So much bitten by the Musquetor that his face is much puffed up & Swelled.” (See Pomp’s Bier was a Bar.)

Home Again

August 17 brought the Charbonneau family to the Mandan villages south of their home village of Metaharta. No Hidatsa chief would agree to go to meet President Jefferson, so Charbonneau’s interpreting services were no longer needed. He was paid “500$ 33 1/3 cents” for translating, a horse, and use of his leather lodge.

Now Clark made, or possibly reiterated, an amazing offer—to see to Jean Baptiste’s education in St. Louis.

I offered to take his little Son a butifull promising child who is 19 months old to which they both himself & wife wer willing provided the Child has been weened. they observed that in one year the boy would be Sufficiently old to leave his mother & he would then take him to me . . . “

After the Expedition

The Charbonneaus went to St. Louis in September 1809, when their son was four. They stayed for about a year and a half, during which time Jean Baptiste was baptized and his father bought land from William Clark. Then Sacagawea became ill and wanted to return to her Hidatsa home. She also was pregnant for the second time, but whether the illness was related is unknown. After selling the land back to Clark, Toussaint hired on with Manuel Lisa’s Missouri Fur Company. In late spring 1811, the couple left Jean Baptiste to Clark’s care and headed up the Missouri River on a Missouri Fur Company boat.

Another passenger on the same boat was lawyer Henry M. Brackenridge, traveling to write about the upper Missouri frontier. He described the couple in this way:

We have on board a Frenchman named Charbonet, with his wife, an Indian woman of the Snake nation, both of whom accompanied Lewis and Clark to the Pacific, and were of great service. The woman, a good creature, of a mild and gentle disposition, was greatly attached to the whites, whose manners and airs she tries to imitate; but she had become sickly and longed to revisit her native country; her husband also, who had spent many years amongst the Indians, was become weary of civilized life.[19]Henry Marie Brackenridge, Views of Louisiana, Together with a Journal of a Voyage up the Missouri River, in 1811 (Pittsburgh: Cramer, Spear and Eichbaum, 1814), 202.

Charbonneau went to work at Lisa’s Fort Manuel (south of today’s Mobridge, South Dakota), but he often had to travel away for negotiations with Gros Ventres, Mandans, Hidatsas, Arikaras, and others. Area Indians were becoming increasingly hostile as more mountain men moved into their lands, and Charbonneau was in demand as a translator during both trade and peacekeeping talks. Sacagawea was busy with baby Lisette, a daughter born apparently in August.[20]An 11 August 1813, court filing in St. Louis listed Lisette as being “about one year old.” Ibid., 117.

Death

John C. Luttig, Lisa’s clerk at Fort Manuel, kept a journal that included this entry for 20 December 1812: “This Evening the Wife of Charbonneau a Snake Squaw, died of a putrid fever[21]“Putrid fever” was a contemporary term for typhus, an infectious disease caused by rickettsia bacteria, transmitted by lice. It was a danger in crowded, confined places, and so was often … Continue reading she was a good and best Woman in the fort, aged about 25 years she left a fine infant girl.”[22]John C. Luttig, Journal of a Fur-Trading Expedition on the Upper Missouri, 1812-1813, ed. Stella M. Drumm, (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1920), 106.

The following year, Luttig was named guardian of Jean Baptiste and Lisette in a St. Louis court document. His name was later replaced with that of William Clark,[23]Morris, 117. who paid for the raising and education of the children in St Louis. When Clark wrote his list of the fates of expedition members sometime between 1825 and 1828, he noted Sacagawea as deceased.

Another story of Sacagawea’s later years and death must be mentioned, the oral tradition of the Eastern Shoshone people.[24]See http://www.easternshoshone.net/EasternShoshoneHistory.htm (Sacagawea’s people were western Shoshones who lived in the present Lemhi River valley, in Idaho.) The story handed down among the Wind River Shoshones is that Sacagawea adopted an Eastern Shoshone man named Bazil, as her son, and in her later years moved to live with him in Wyoming. There, according to Eastern Shoshone tradition, she is said to have died in 1884, at nearly 100 years of age, and was buried at Fort Washakie on the Wind River [Shoshone] Indian Reservation.

Funded in part by a grant from the National Park Service, Challenge Cost Share Program

Notes

| ↑1 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 5:114, 17 August 1805. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Settled with Touisant Chabono for his Services as an enterpreter the price of a horse and Lodge purchased of him for public Service in all amounting to 500$ 33 1/3 cents.” Ibid., 8:305, 17 August 1806. |

| ↑3 | Ibid., 6:91, 28 November 1806. |

| ↑4 | Ibid., 5:8-9. |

| ↑5 | For more, see Defining ‘Squaw’. |

| ↑6 | Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 188, lists Toussaint Charbonneau’s parents as Jean Baptiste Charbonneau and Marguerite Deniau. |

| ↑7 | Actually hog peanuts, Amphicarpa bracteata, which meadow mice or voles collect and store. Moulton, ed., Journals, 4:18n6. |

| ↑8 | The large Indian breadroot, formerly known as Psoralea esculenta, is a member of the pea family now known as Pediomelum esculentum—pee-dee-oh-MEE-lum “plain apple” and ess-kyu-LEN-tum “fit for eating.” |

| ↑9 | Although it was known as Crooked Creek for many years, the name Sacagawea River has been restored. Ibid., 4:175n5. |

| ↑10 | David J. Peck, Or Perish in the Attempt: Wilderness Medicine in the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Helena, MT: Farcountry Press, 2002, 161-62. |

| ↑11 | See also A Flash Flood. |

| ↑12 | The earlier ones were on 22 August 1804, for nomination of a sergeant to replace the deceased Floyd, and 9 June 1805 on which “fork” at the Missouri-Marias confluence to follow. |

| ↑13 | Clark used the name again when writing to Toussaint Charbonneau from the Arikara villages on the Missouri on 20 August 1806, to reiterate his invitation: ” . . . bring down you Son your famn [femme] Janey had best come along with you to take care of the boy untill I get him.” Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854; 2nd ed.; 2 vols. (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:315. |

| ↑14 | Long bones of the upper leg, which are filled with fatty connective tissue where blood cells are produced. |

| ↑15 | Moulton identifies these as likely from the long-tailed weasel, Mustela frenata, 6:138n2. |

| ↑16 | A more detailed description of the course of treatment appears in Peck, 252-53. |

| ↑17 | Nicholas Biddle, with information from William Clark or George Shannon, amended the measurements to 15 miles by 30. |

| ↑18 | Modern Interstate 90 crosses Bozeman Pass between Bozeman and Livingston, Montana. |

| ↑19 | Henry Marie Brackenridge, Views of Louisiana, Together with a Journal of a Voyage up the Missouri River, in 1811 (Pittsburgh: Cramer, Spear and Eichbaum, 1814), 202. |

| ↑20 | An 11 August 1813, court filing in St. Louis listed Lisette as being “about one year old.” Ibid., 117. |

| ↑21 | “Putrid fever” was a contemporary term for typhus, an infectious disease caused by rickettsia bacteria, transmitted by lice. It was a danger in crowded, confined places, and so was often called “camp fever,” “ship fever,” “hospital fever,” or “prison fever.” Its symptoms included weakness to the extent of being unable to walk or even sit up, high fever, headache, delirium, and red spots on the body. (The last led to the naming of unrelated typhoid fever—an intestinal illness sharing that symptom, but caused by salmonella bacteria.) |

| ↑22 | John C. Luttig, Journal of a Fur-Trading Expedition on the Upper Missouri, 1812-1813, ed. Stella M. Drumm, (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1920), 106. |

| ↑23 | Morris, 117. |

| ↑24 | See http://www.easternshoshone.net/EasternShoshoneHistory.htm |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.